riverhead books

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Originally published in France as La naissance de la pense scientifique: Anaximandre de Milet and later as Anaximandre de Milet, ou la naissance de la pense scientifique by Carlo Rovelli Dunod diteur 2009, 2015, 2020 (new presentation), Malakoff

First English language edition published as The First Scientist: Anaximander and His Legacy by Westholme Publishing, 2011. English translation copyright 2011 by Penguin Random House Ltd.

This edition published simultaneously in Great Britain as Anaximander and the Nature of Science by Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, and in the United States by Riverhead, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, in 2023

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

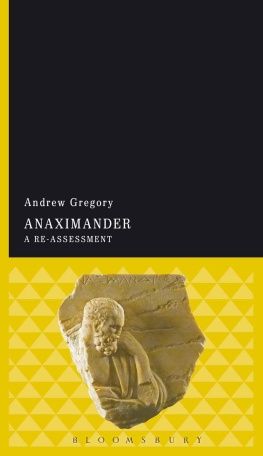

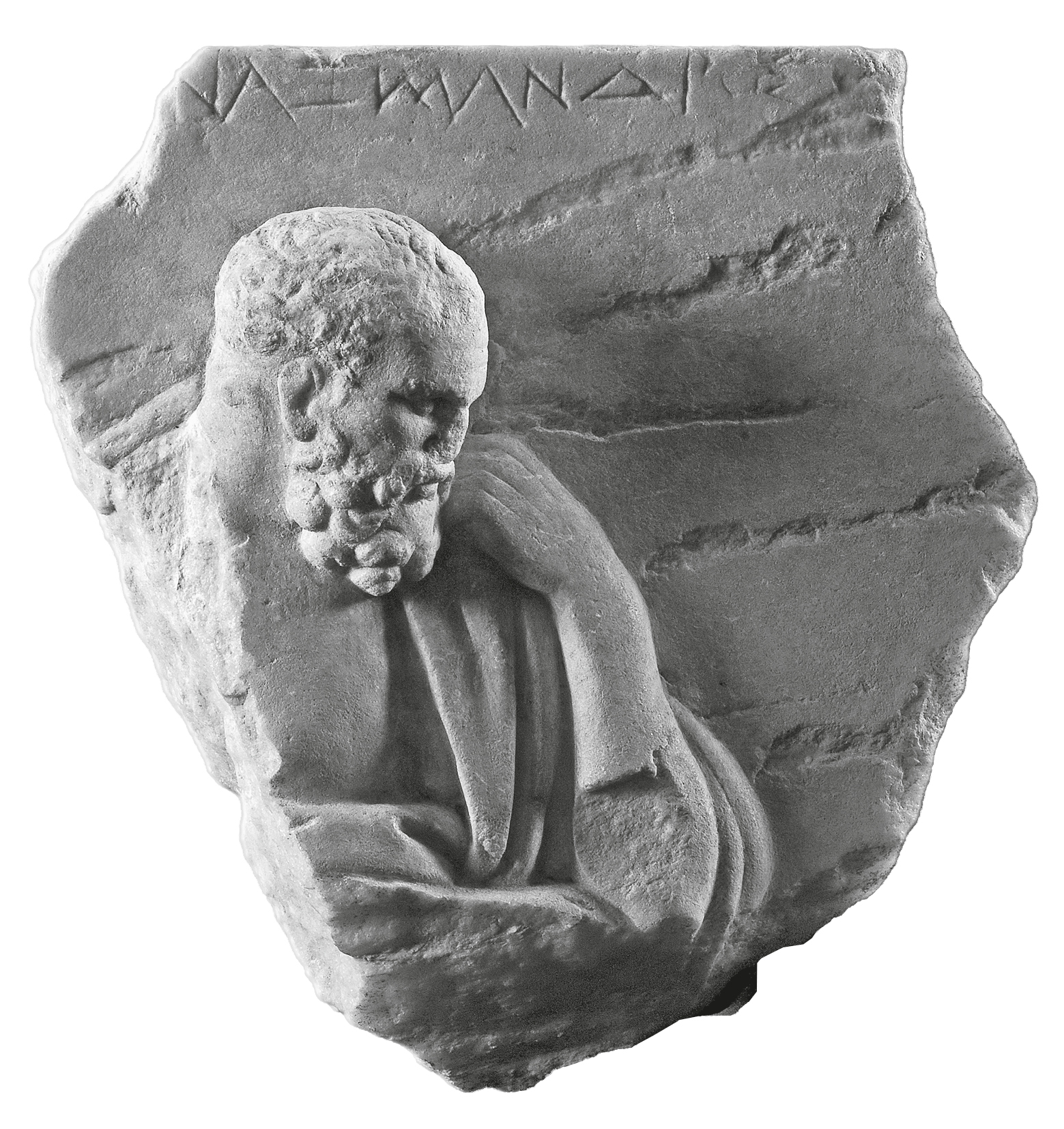

A relief of Anaximander. (Courtesy of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, Special Superintendence for the Archaeological Heritage of Rome)

Riverhead and the R colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rovelli, Carlo, 1956 author. | Rosenberg, Marion Lignana, translator.

Title: Anaximander : and the birth of science / Carlo Rovelli ; translated by Marion Lignana Rosenberg.

Other titles: Che cos la scienza. English

Description: New York : Riverhead Books, 2023. | Translation of: Che cos la scienza : la rivoluzione di Anassimandro, and published in French as La naissance de la pense scientifique : Anaximandre de Milet, and also published as Anaximandre de Milet, ou la naissance de la pense scientifique; previously published in English as The First Scientist: Anaximander and His Legacy | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022036584 (print) | LCCN 2022036585 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593542361 (paperback) | ISBN 9780593542378 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Anaximander. | AstronomyHistoryTo 1500. | SciencePhilosophy. | Philosophy, Ancient. | Cosmology, Ancient. | ScienceMethodologyHistory to 1500.

Classification: LCC B208.Z7 R6913 2023 (print) | LCC B208.Z7 (ebook) | DDC 182dc23/eng/20220822

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022036584

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022036585

Cover design: Jason Booher

Book design by Daniel Lagin, adapted for ebook by Maggie Hunt

pid_prh_6.0_142645830_c0_r0

Contents

_142645830_

Rerum fores aperuisse, Anaximander Milesius traditur primus.

It is said that Anaximander of Miletus first opened the doors of nature.

Pliny, Natural History II

FIGURE 1A, LEFT. Most early human civilizations viewed the world as the Heavens above and the Earth below. FIGURE 1B, RIGHT. The ancient Greeks saw the Earth as a stone floating in space.

Introduction

Human civilizations have always believed that the world consisted of the Heavens above and the Earth below (figure 1a). Beneath the Earth, to keep it from falling, there had to be more earth; or perhaps an immense turtle on the back of an elephant, as in some Asian myths; or gigantic columns like those supporting the Earth according to the Bible. This vision of the world was shared by the Egyptians, the Chinese, the Mayans, the peoples of ancient India and sub-Saharan Africa, the Hebrews, Native Americans, the ancient Babylonian empires, and all other cultures of which we have evidence.

All but one: the Greek world. Already in the classical era, the Greeks saw the Earth as a stone floating in space without falling (figure 1b). Beneath the Earth, there was neither more earth without limit, nor turtles, nor columns, but rather the same sky that we see over our heads. How did the Greeks manage to understand so early that the Earth is suspended in the void and that the Heavens continue under our feet? Who understood this, and how?

The man who made this enormous leap in understanding the world is the main character in this story: , Anaximander, who lived twenty-six centuries ago in Miletus, a Greek city on the coast of what is now Turkey. This discovery alone would make Anaximander one of the intellectual giants of the ages. But Anaximanders legacy is still greater. He paved the way for physics, geography, meteorology, and biology. Even more important than these contributions, he set in motion the process of rethinking our worldviewa search for knowledge based on the rejection of any obvious-seeming certainty, which is one of the main roots of scientific thinking.

The nature of scientific thinking is the second subject of this book. Science, I believe, is a passionate search for always newer ways to conceive the world. Its strength lies not in the certainties it reaches but in a radical awareness of the vastness of our ignorance. This awareness allows us to keep questioning our own knowledge, and, thus, to continue learning. Therefore the scientific quest for knowledge is not nourished by certainty, it is nourished by a radical lack of certainty. Its way is fluid, capable of continuous evolution, has immense strength and a subtle magic. It is able to overthrow the order of things and reconceive the world time and again.

This reading of scientific thinking as subversive, visionary, and evolutionary is quite different from the way science was understood by the positivist philosophers, but is also different from the fragmented, sometimes dry image of science provided by some more modern philosophical reflections on science. The aspect of science that I seek to illuminate in these pages is its critical and rebellious ability to reimagine the world again and again.

If this reimagining of the world is a central aspect of the scientific enterprise, then the beginning of this adventure is not to be sought in Newtons laws of motion, in Galileos experiments, or in Francis Bacons reflections. Nor even in the early and mathematical constructions of Alexandrian astronomy. It must be sought in what can be called the first great scientific revolution in human historyAnaximanders revolution.

There is no doubt that Anaximanders importance in the history of thought has been underrated. I believe that this has happened for several reasons. On the one hand, in the ancient world, his contributions were recognized by authors of a scientific bent, including Pliny (as quoted in the epigraph to this book), but Anaximander was generally seen by the ancients, including Aristotle, as the proponent of a naturalistic approach to knowledge that was fiercely opposed by other cultural currents and that had not yielded much in the way of results. The naturalistic project, indeed, had yet to bear the rich fruits it would bear with modern science, after a long process of maturation and numerous methodological adjustments.