INTRODUCTION

Rosalind Thomas

1. Opening Remarks

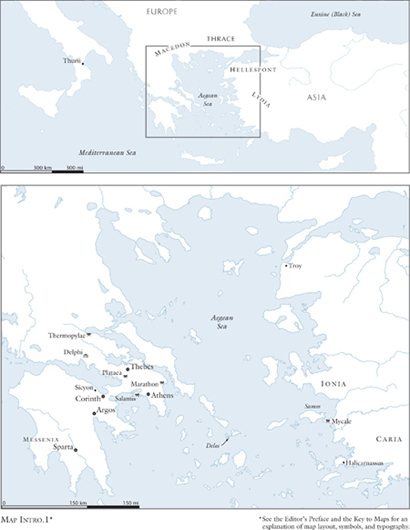

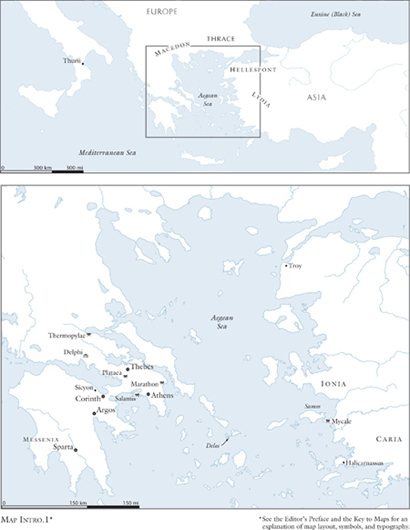

1.1. Herodotus Histories trace the conflict between the Greeks and the Persians which culminated in the Persian Wars in the great battles of Thermopylae, Salamis, Plataea, and Mycale (480-479), a generation or so before he was writing. He described his theme as comprising both the achievements of Greeks and barbarians, and also the reasons why they came into conflict (Book 1, Proem). This suggests that he sought the causes of the conflict in factors that took one back deep into the past and into the characteristics of each society. He implies that he saw the deep-seated causes in cultural antagonism of Greek and non-Greek, but he went out of his way to describe the achievements and customs of many non-Greek peoples with astonishing sensitivity and lack of prejudice. The Histories are the first work in the Western tradition that are recognizably a work of history to our eyes, for they cover the recent human past (as opposed to a concentration on myths and legends), they search for causes, and they are critical of different accounts. Herodotus own description of them as an inquiry, a bistorte, has given us our word history, and he has been acknowledged as the father of history. He also has a claim to be the first to write a major work on geography and ethnography. His interests were omnivorous, from natural history to anthropology, from early legend to the events of the recent past: he was interested in the nature of the Greek defense against the Persians, or the nature of Greek liberty, as well as in stranger and more exotic tales about gold-digging ants or other wondrous animals in the East. The Histories are the first long work in prose (rather than verse) which might rival the Homeric epics in scale of conception and length. Shorter works in prose had appeared before, but the Histories must in their time have been revolutionary.

1.2. Who, then, was Herodotus? As with most ancient Greek authors, we have little reliable information, and the later ancient biographers may have invented biographical facts by drawing from the content of the Histories themselves, as was common in ancient biographies of writers. He was born in Halicarnassus (see below). Unlike in many modern travelogues, the main focus of interest is not on the traveling itself but on the information it yields, so again the personal elements are not extensive. His life spanned much of the fifth century: here there is no reason to doubt the ancient tradition that he was born at roughly the time of the Persian Wars (480-479), and he probably lived into the 420s, since the Histories make references to events in Greece early in the Pelo-ponnesian War of 431-404. It is usually thought that he was active as researcher and writer from the 450s to the 420s. The Histories clearly constituted a lifes work.

2. The Historical Background

2.1. The beginning of this period saw the triumph of the Greek mainland states over the might of the Persian Empire, first in the initial invasion of 490 and the battle of Marathon,on the grounds that the Athenians did most to defeat the Persians (e.g., Thucydides 1.73.2-75.2: although we are rather tired of continually bringing up this subject [the Persian War], 1.73.2). In other words, the Persian Wars were still very much a living part of Greek politics in the 430s and 420s and the period during which Herodotus was researching. They played an important role in the rhetoric and diplomacy of the time. Athens could and did claim that she had done more than any other Greek city to help Greece keep her freedom; Sparta and Corinth now asserted that Athens herself was enslaving Greece. Freedom is central to Herodotus Histories, and it played a crucial part in inter-state political argument and antagonism in the later fifth century.

2.2. Herodotus Histories need to be seen in part against this background, even though in formal terms they describe events only down to the end of the Persian Wars in 479. For he takes as his explicit theme the conflict between the Greeks and the barbarians, as he puts it in the introduction, and after tracing this conflict back to the earliest times, he gradually works up to the full narrative of the Greek-Persian conflict in the Ionian Revolt of 499-494 (Books 5-6), and to the two Persian invasions of mainland Greece of 490 and 480 (Books 6-9). Herodotus Histories stop on the brink of the creation of the Athenian Empire: they end their main narrative at the point where the Greeks in Asia Minor, helped by the Greek fleet under the Spartan Leotychidas, have won a decisive victory against the Persian forces at Mycale in Asia Minoron the very same day on which the Greek army in central Greece under Pausanias had won the victory at Plataea, which forced the Persians to withdraw entirely from Greece. The Asia Minor Greeks were taken into the anti-Persian alliance of the Greek allies (9.106), and the victorious Greek forces sailed up to the Hellespont to continue aggressive operations against Persia and free more Greek cities. The Spartans and Peloponnesians went home, fatally leaving the Athenians in charge (9.114; though they were to send another commander out later), and Herodotus narrative ends with the Athenian actions in the Hellespont, which many scholars have seen as an ominous portent of the future (9.120).

2.3. If we imagine Herodotus trying to collect accounts, to take oral testimony, and to gather personal or collective memories about the Persian Wars, then we can assume that he would have been talking to people who had actually been involved, who perhaps had fought in the war or whose relations had done so; and since the effects of the Persian Wars were still immediate and strong, and charges of Medismby stressing and criticizing his sources and accepted traditions, but it was his successor Thucydides who really solidified and in fact narrowed the idea of history as a critical study of past events (and only past events, as opposed to ethnography, mythology, or geography). This definition of history as the study of past political and military events is something of an anachronism for Herodotus, who, after all, included so much more in his inquiry: we would be applying a later conception to an earlier achievement which was conceived in earlier and therefore different terms (see below). It also ignores the complex structure of his work and its overall unity, for in the Histories geography and customs have a large explanatory role in the course of events, and the interweaving of geography, ethnography, and the narrative of events is very finely done, not as one might expect if one or the other area was somehow tacked on later. Besides, wonders and achievements are worthy of relation/telling (axiologotatoi), in Herodotus phrase, in their own right. Egypt was worthy of a longer description because it had more marvels than any other place (2.35.1). Wonders were simply part of his subject matter.