Makers of History

Charles I.

by

JACOB ABBOTT

WITH ENGRAVINGS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

1901

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1848, by

HARPER & BROTHERS,

In the Clerks Office of the Southern District of New York.

Copyright, 1876, by JACOB ABBOTT.

Table of Contents

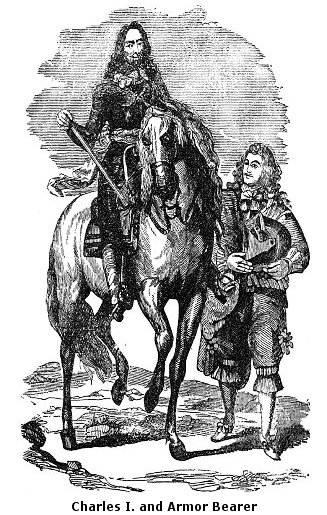

ENGRAVINGS

PREFACE.

The history of the life of every individual who has, for any reason, attracted extensively the attention of mankind, has been written in a great variety of ways by a multitude of authors, and persons sometimes wonder why we should have so many different accounts of the same thing. The reason is, that each one of these accounts is intended for a different set of readers, who read with ideas and purposes widely dissimilar from each other. Among the twenty millions of people in the United States, there are perhaps two millions, between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five, who wish to become acquainted, in general, with the leading events in the history of the Old World, and of ancient times, but who, coming upon the stage in this land and at this period, have ideas and conceptions so widely different from those of other nations and of other times, that a mere republication of existing accounts is not what they require. The story must be told expressly for them. The things that are to be explained, the points that are to be brought out, the comparative degree of prominence to be given to the various particulars, will all be different, on account of the difference in the situation, the ideas, and the objects of these new readers, compared with those of the various other classes of readers which former authors have had in view. It is for this reason, and with this view, that the present series of historical narratives is presented to the public. The author, having had some opportunity to become acquainted with the position, the ideas, and the intellectual wants of those whom he addresses, presents the result of his labors to them, with the hope that it may be found successful in accomplishing its design.

CHAPTER I. HIS CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH .

1600-1622

King Charles the First was born in Scotland. It may perhaps surprise the reader that an English king should be born in Scotland. The explanation is this:

They who have read the history of Mary Queen of Scots, will remember that it was the great end and aim of her life to unite the crowns of England and Scotland in her own family. Queen Elizabeth was then Queen of England. She lived and died unmarried. Queen Mary and a young man named Lord Darnley were the next heirs. It was uncertain which of the two had the strongest claim. To prevent a dispute, by uniting these claims, Mary made Darnley her husband. They had a son, who, after the death of his father and mother, was acknowledged to be the heir to the British throne, whenever Elizabeths life should end. In the mean time he remained King of Scotland. His name was James. He married a princess of Denmark; and his child, who afterward was King Charles the First of England, was born before he left his native realm.

King Charless mother was, as has been already said, a princess of Denmark. Her name was Anne. The circumstances of her marriage to King James were quite extraordinary, and attracted great attention at the time. It is, in some sense, a matter of principle among kings and queens, that they must only marry persons of royal rank, like themselves; and as they have very little opportunity of visiting each other, residing as they do in such distant capitals, they generally choose their consorts by the reports which come to them of the person and character of the different candidates. The choice, too, is very much influenced by political considerations, and is always more or less embarrassed by negotiations with other courts, whose ministers make objections to this or that alliance, on account of its supposed interference with some of their own political schemes.

As it is very inconvenient, moreover, for a king to leave his dominions, the marriage ceremony is usually performed at the court where the bride resides, without the presence of the bridegroom, he sending an embassador to act as his representative. This is called being married by proxy. The bride then comes to her royal husbands dominions, accompanied by a great escort. He meets her usually on the frontiers; and there she sees him for the first time, after having been married to him some weeks by proxy. It is true, indeed, that she has generally seen his picture , that being usually sent to her before the marriage contract is made. This, however, is not a matter of much consequence, as the personal predilections of a princess have generally very little to do with the question of her marriage.

Now King James had concluded to propose for the oldest daughter of the King of Denmark and he entered into negotiations for this purpose. This plan, however, did not please the government of England, and Elizabeth, who was then the English queen, managed so to embarrass and interfere with the scheme, that the King of Denmark gave his daughter to another claimant. James was a man of very mild and quiet temperament, easily counteracted and thwarted in his plans; but this disappointment aroused his energies, and he sent a splendid embassy into Denmark to demand the kings second daughter, whose name was Anne. He prosecuted this suit so vigorously that the marriage articles were soon agreed to and signed. Anne embarked and set sail for Scotland. The king remained there, waiting for her arrival with great impatience. At length, instead of his bride, the news came that the fleet in which Anne had sailed had been dispersed and driven back by a storm, and that Anne herself had landed on the coast of Norway.

James immediately conceived the design of going himself in pursuit of her. But knowing very well that all his ministers and the officers of his government would make endless objections to his going out of the country on such an errand, he kept his plan a profound secret from them all. He ordered some ships to be got ready privately, and provided a suitable train of attendants, and then embarked without letting his people know where he was going. He sailed across the German Ocean to the town in Norway where his bride had landed. He found her there, and they were married. Her brother, who had just succeeded to the throne, having received intelligence of this, invited the young couple to come and spend the winter at his capital of Copenhagen; and as the season was far advanced, and the sea stormy, King James concluded to accept the invitation. They were received in Copenhagen with great pomp and parade, and the winter was spent in festivities and rejoicings. In the spring he brought his bride to Scotland. The whole world were astonished at the performance of such an exploit by a king, especially one of so mild, quiet, and grave a character as that which James had the credit of possessing.