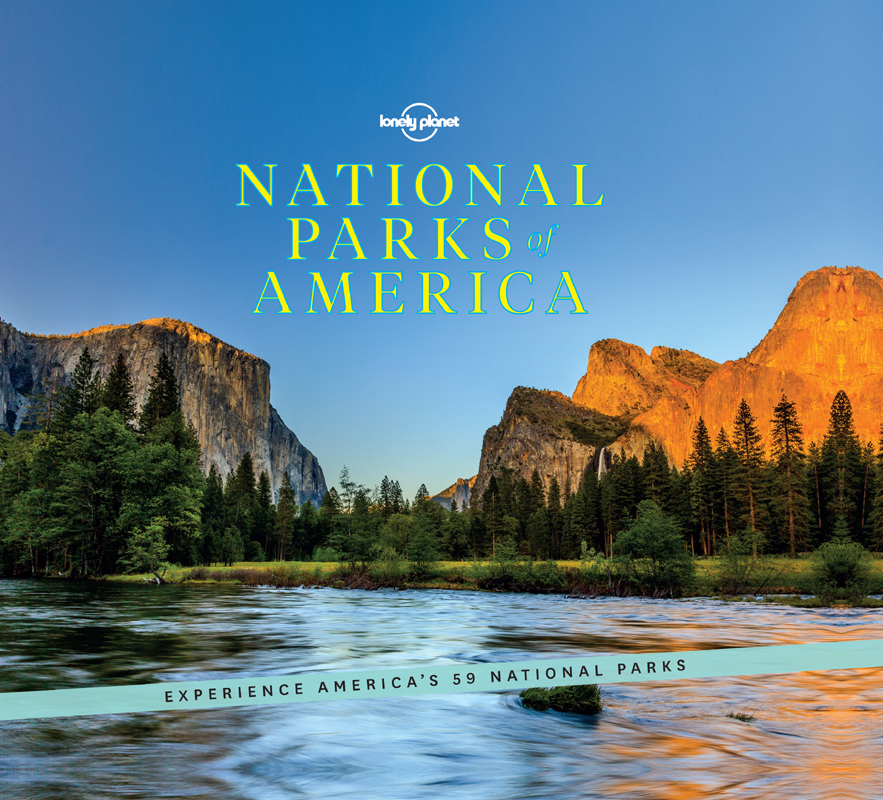

Introduction

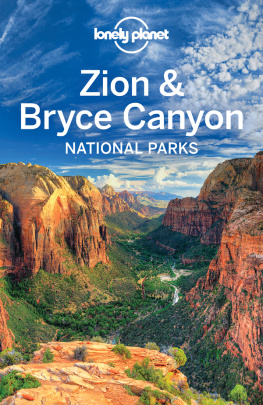

I got lucky the first time that I visited an American national park. I was in Utah and with a few days free before my flight out of the state, and a pair of hiking boots in my luggage, I headed for the closest national park, not knowing what Id find. That park was Bryce Canyon (see p46). It was October and there had already been some flurries of snow. When I arrived at a viewpoint overlooking a vast bowl that I later discovered was called Silent City snow remained in the suns shadow, highlighting every ridge and feature. But glowing red, yellow and orange under the blue sky were row upon row of Bryce Canyons extraordinary hoodoos, narrow spires of rock formed as fins created by water erode into columns. It was an epiphany.

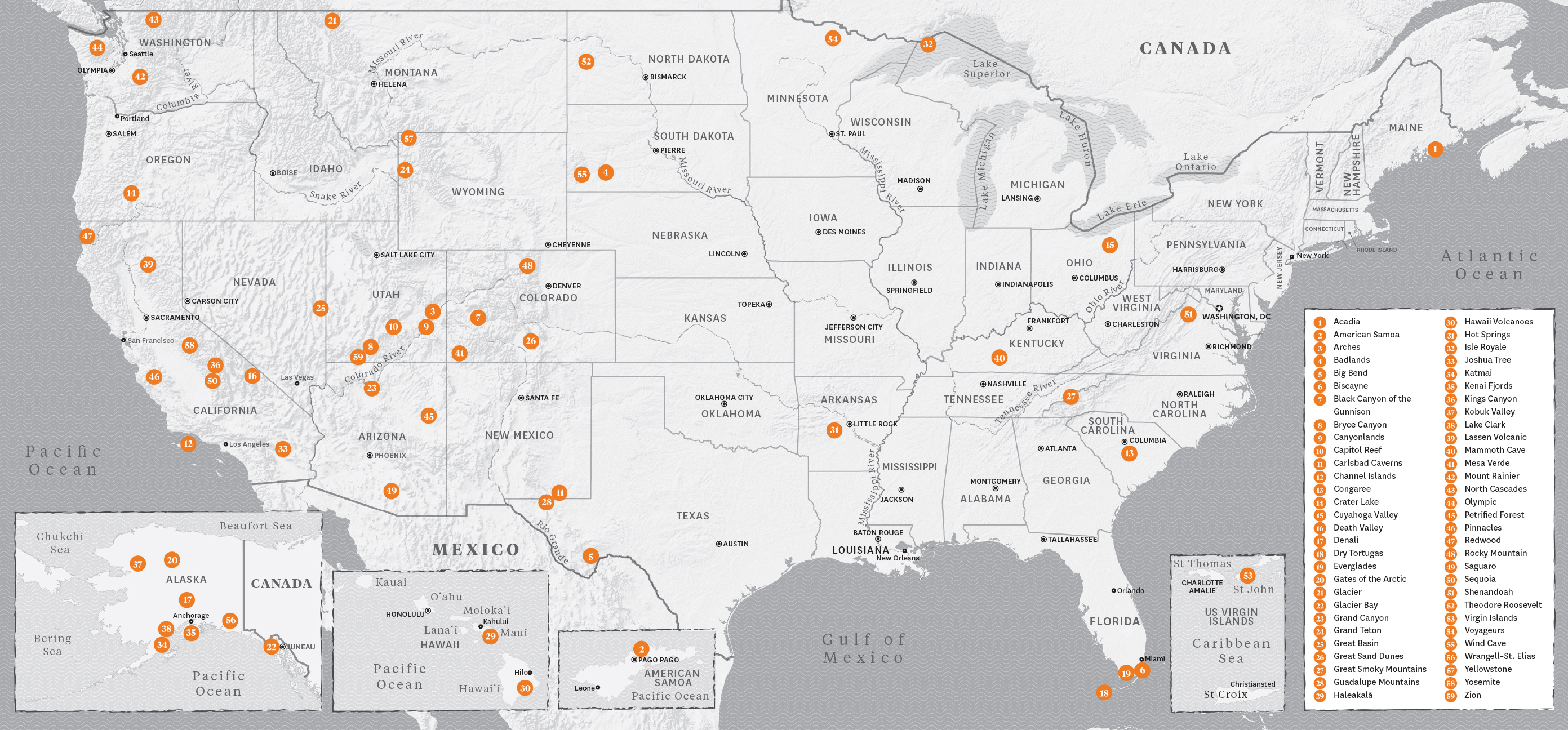

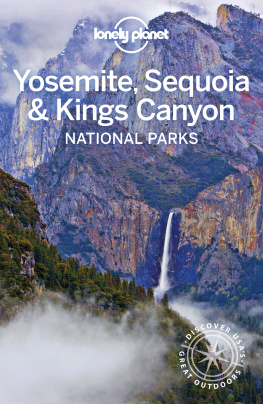

Americas national parks are full of such marvels: the worlds largest trees in Sequoia; its most spectacular geothermal site in Yellowstone; the grandest canyon. Its around these world-famous places that the story of the National Parks Service is woven. President Woodrow Wilson created the National Parks Service (NPS) on August 25, 1916, but the drive to protect some of Americas most remarkable wild spaces, to be used and preserved for the benefit of mankind, began in the 1860s.

Perhaps the movements most eloquent advocate was Scottish-born writer John Muir. He had worked in the Yosemite Valley in the 1860s and later, in 1903, camped there under the stars with President Theodore Roosevelt, who created five national parks during his administration. Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people, Muir wrote in Our National Parks, are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity

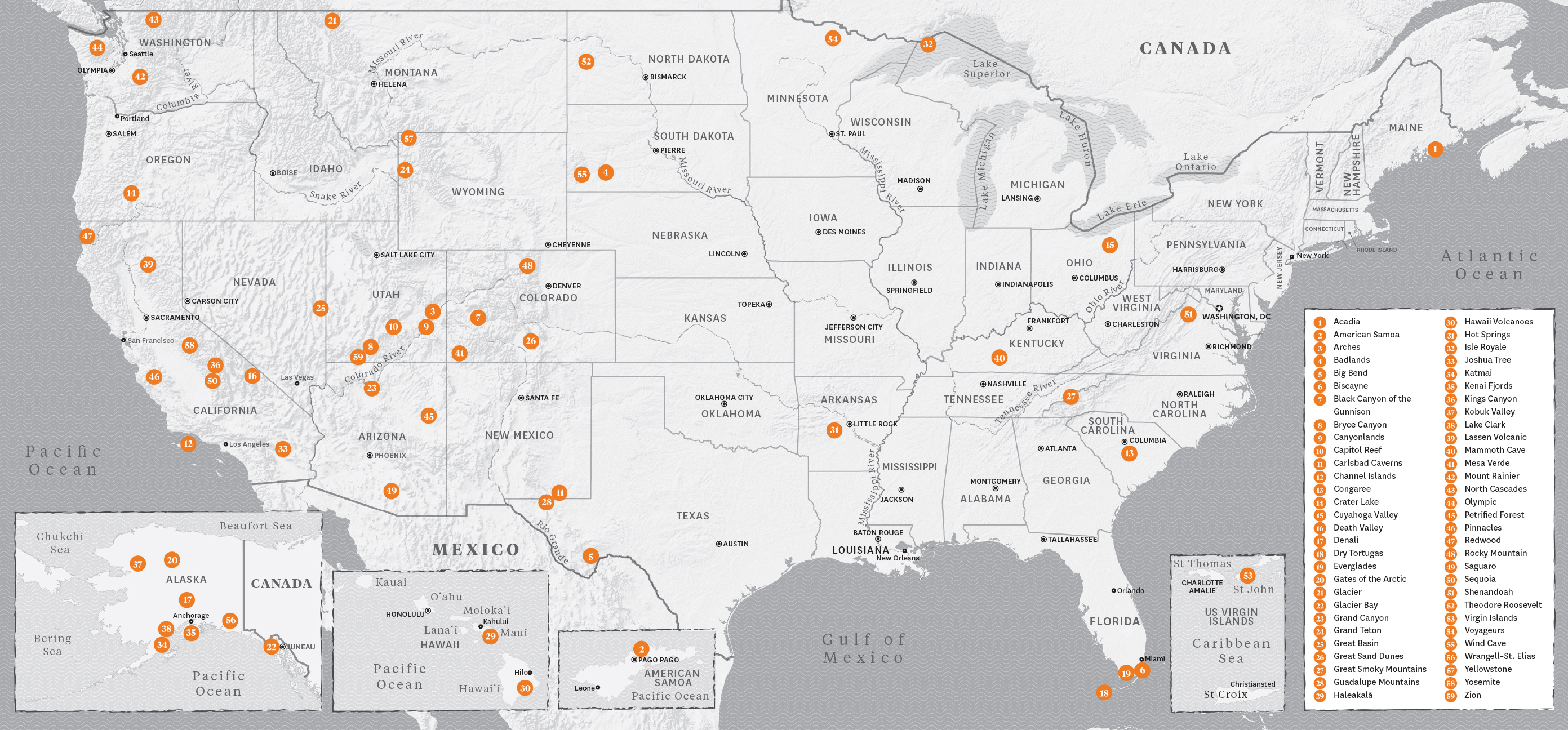

This book is intended to be a practical introduction to each of Americas 59 national parks, distilled by Lonely Planets expert authors. We highlight the best activities and trails, explain how to get there and where to stay, show you the wildlife to watch out for, and suggest ideal itineraries. Whether youre lucky enough to have a park on your doorstep or need to travel further, we hope that the following pages inspire you to explore what Stephen Mather, the first director of the NPS, described as Americas national properties.

GRAND PRISMATIC GEYSER, YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK.

Getty Images | KWIKTOR

ME

ME

Acadia National Park

See New England at its most glorious from the seaside cliffs of Acadia, at the easternmost tip of the United States.

Youre sitting on a smooth granite outcropping, the dark ocean pounding some 1530ft (466m) below. Finally, you see it: a blood-red finger of sunlight piercing the horizon. Slowly, the dark clouds go rosy pink, the ocean becoming an ever-lightening purple. This is sunrise on Cadillac Mountain in Acadia National Park, the first place the sun shows its face in the United States.

Much like New England itself, Acadia pings between utterly civilized and utterly wild. Theres high tea on the lawn and theres harsh, crashing gray surf along rocky beaches. There are horse-drawn carriage rides and hikes through leg-slashing thorn bushes. Theres lobster ravioli in thyme butter at the elegant bistros of Bar Harbor and theres roasting hot dogs over an open fire at the parks primitive campgrounds.

Painters and other artists discovered the Acadia area in the mid-1800s, spending summers boarding with local fisherman and painting the stunning scenery. These rusticators grew in number so quickly there were soon several dozen hotels catering to their needs. By the 1890s, Gilded Era captains of industry were arriving to summer in enormous cottages on the island. But the Great Depression, WWII and, finally, a huge wildfire in 1947 destroyed this lavish lifestyle, along with most of the cottages.

In the early 1900s, George Dorr, heir to a New England textile fortune, began working to preserve the area from the onslaught of tourism and industry. The land that he and others donated to the federal government became Lafayette National Park in 1919, the first national park east of the Mississippi; its name was changed to Acadia in 1929. Today, Acadia and the nearby town of Bar Harbor still attract moneyed Eastern elites who sail, hold charity balls and dine in the areas many fine restaurants. But like all national parks, Acadia is a democratic place, welcoming everyone.

Jordan Pond.

Getty Images | CHRIS MURRAY

Toolbox

When to go

The park gets the usual July/August rush, but its just as pretty (if a bit colder) in May, June and September. In October, when the leaves burst into flaming reds and golds, its positively heavenly.

Getting there

Acadia is on the coast of Maine, near the town of Bar Harbor. Most of the park is on Mt Desert (pronounced dessert, as in cake) Island. The nearest sizeable airport is in Bangor, about an hours drive from the park.

Park in numbers

Area covered (sq miles)

1530

Highest point: Cadillac Mountain (ft)

Miles of shoreline

Stay here

Blackwoods Campground

The only one of Acadias three campgrounds open year-round, Blackwoods has tent sites set in shady forest. Roll out of your tent and onto the trail to Cadillac Mountain and other popular hikes. In summer, facilities such as a store and shower are available; in winter its primitive all the way. The shuttle stops outside.

Holland Inn

Since there are no accommodations other than campgrounds within the national park, most visitors stay in nearby Bar Harbor. This white wooden inn has an austere Yankee charm, with friendly innkeepers. Its on a quiet side street just a few minutes walk from the cafes and boutiques of Bar Harbor village.

Saltair Inn

Built in 1887 as a summer cottage for a New York businessman and his wife, this Victorian mansion is now a charming B&B. Guests watch the light play over Frenchman Bay from the deck. Owners earn kudos for their advice about local sights and activities.

Do this!

Mountain summiting

The gem in Acadias crown, Cadillac Mountain rises 1530ft (466m) above the crashing surf. The highest point on the North Atlantic seaboard, its the first place to see the sun rise in America for much of the year. You can hike Cadillac but the easiest way to get here is to drive the 3.5-mile (5.6km) road to the top. Come at dawn bundled in your wooliest sweater to watch light break over Frenchman Bay.

Next page

ME

ME