Contents

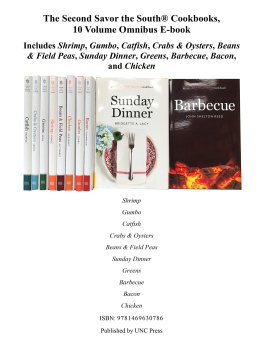

SAVOR THE SOUTH cookbooks

Gumbo, by Dale Curry (2015)

Shrimp, by Jay Pierce (2015)

Catfish, by Paul and Angela Knipple (2015)

Sweet Potatoes, by April McGreger (2014)

Southern Holidays, by Debbie Moose (2014)

Okra, by Virginia Willis (2014)

Pickles and Preserves, by Andrea Weigl (2014)

Bourbon, by Kathleen Purvis (2013)

Biscuits, by Belinda Ellis (2013)

Tomatoes, by Miriam Rubin (2013)

Peaches, by Kelly Alexander (2013)

Pecans, by Kathleen Purvis (2012)

Buttermilk, by Debbie Moose (2012)

2015 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America.

SAVOR THE SOUTH is a registered trademark of the

University of North Carolina Press, Inc.

Designed by Kimberly Bryant and set in Miller and

Calluna Sans types by Rebecca Evans.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

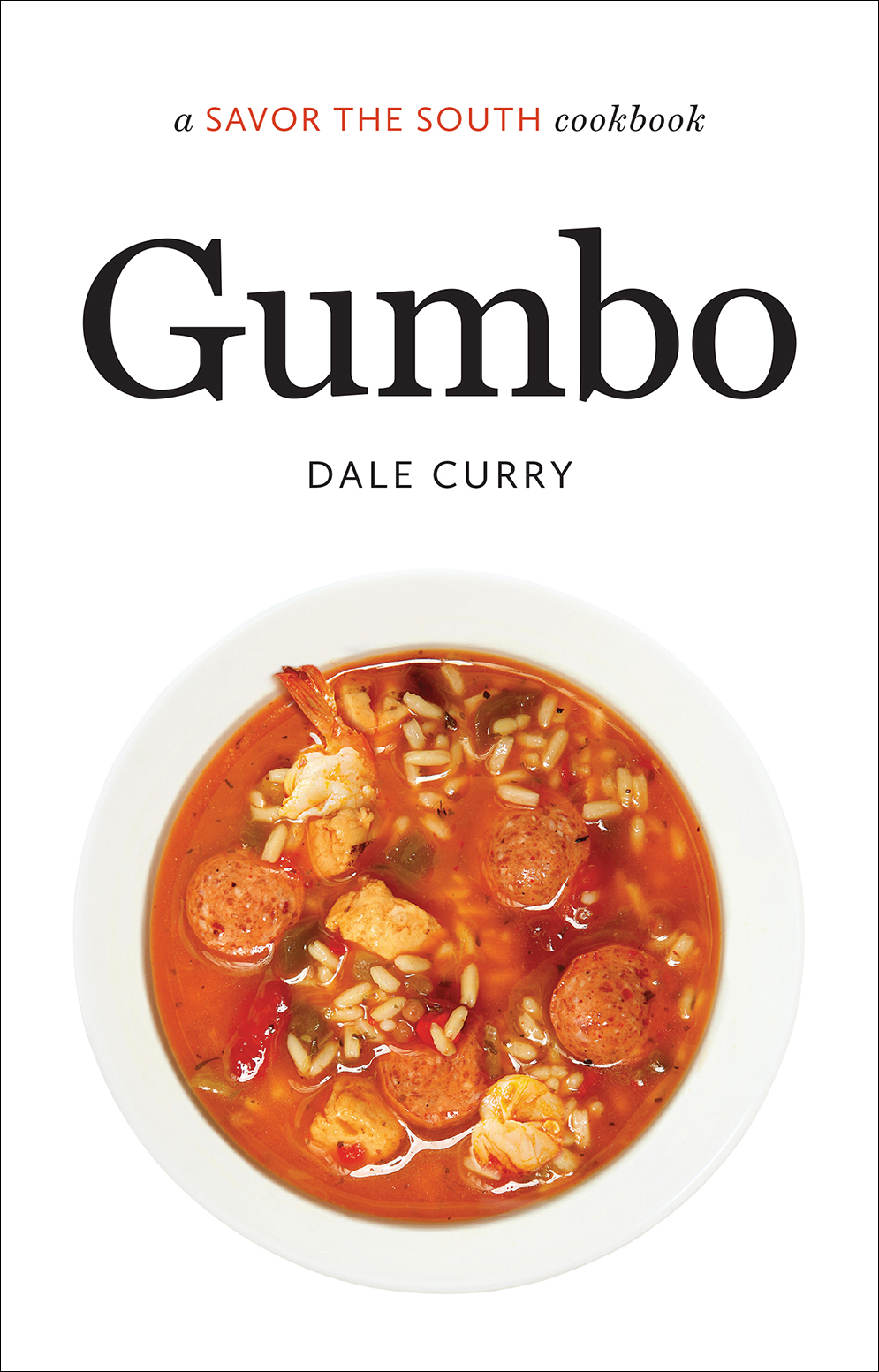

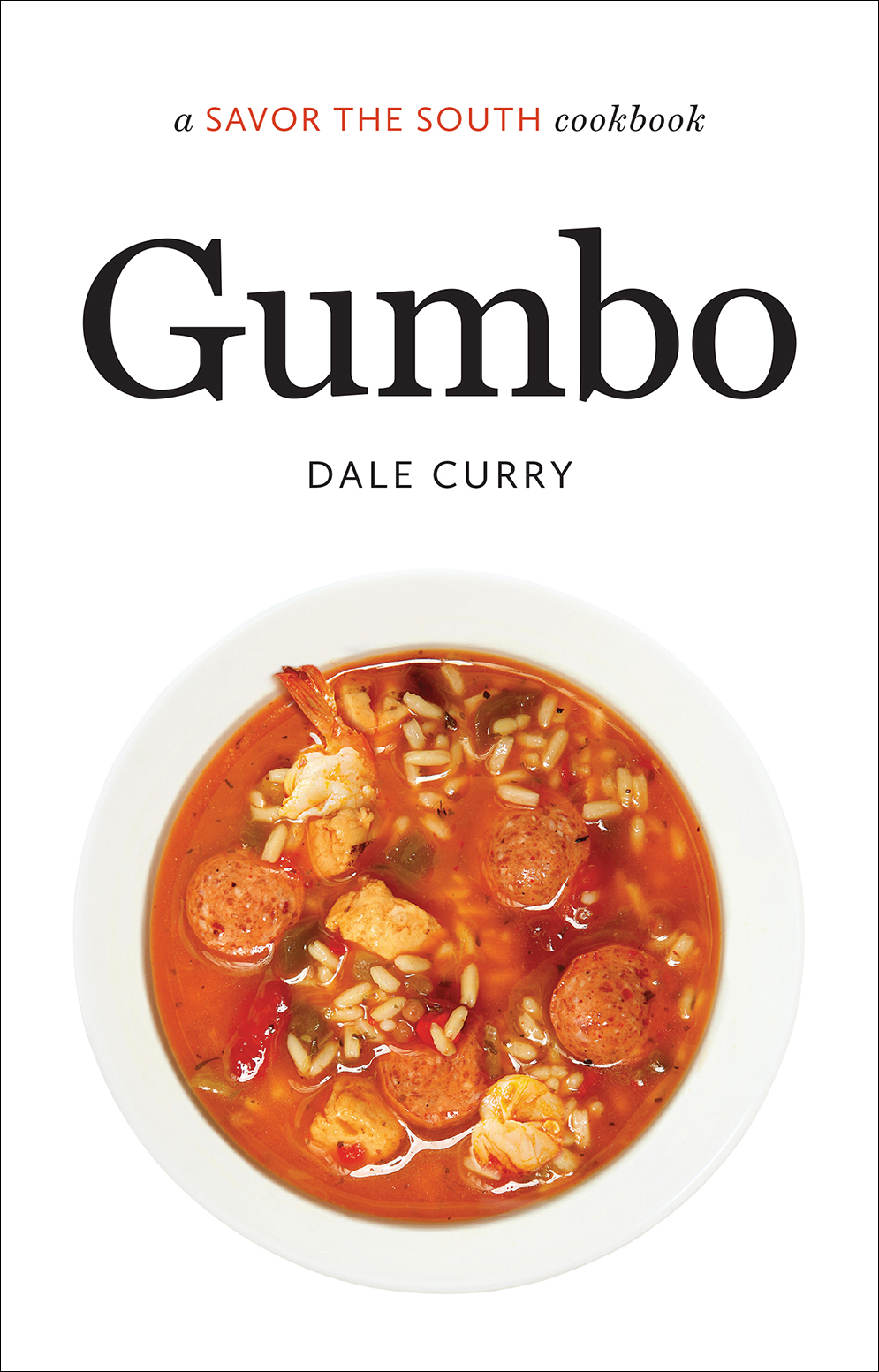

Jacket illustration: bowl, ksena32/Fotolia.com;

shrimp, smuay/Fotolia.com; gumbo, JaimieDuplass/Fotolia.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Curry, Dale.

Gumbo / by Dale Curry.

pages cm.(Savor the South cookbooks)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-4696-2192-0 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-2268-2 (ebook)

1. Gumbo (Soup) 2. Cooking, AmericanSouthern style. I. Title.

TX757.C8685 2015

641.813dc23 2014040784

Chef Emeril Lagasses Gulf Coast Gumbo recipe courtesy of Emeril Lagasse, MSLO, Inc. All rights reserved.

To Matthew, Benjamin, Blair, and Allison

Contents

And a few Jambalaya

SIDEBAR

a SAVOR THE SOUTH cookbook

Gumbo

Introduction

When you live in New Orleans, your house becomes part home, part hotel because everyone you ever knew wants to come for a visit. There are many reasons for thismusic, architecture, and the joie de vivrebut the big draw is the food, plain and simple.

Long ago, I established my plan for receiving these welcome guests: change the sheets and make a pot of gumbo. After that, theyre on their own. Nobodys complained yet; I still have friends from childhood and college coming on a regular basis. The first thing they want when they get here is gumbo. While its a regular on my menu, the dish is not a part of their weekly diets because they come from such locales as New York, Kansas, and California. Wherever theyre from, though, their favorite version is seafood gumbo with crabs, shrimp, and oysters coming together in a single pot.

There is something about the smell of a simmering pot of gumbo that says Louisiana. Its taste and aroma are unique. A change of atmosphere is noticeable when you drive south on the I-10 and smell the swamps and watch the egrets fly from one moss-covered cypress to another. Upon arrival, your first meal confirms a difference: You are in south Louisiana.

New Orleans is also known as the Big Easy, and one of a visitors first experiences is sure to be a bowl of gumbo. It tingles your taste buds with spicy cayenne pepper and produces a taste you never forget. This pungent concoction of fresh seafood, meat, or poultry swimming in a dark liquid is the star of a cuisine that is unique in the world.

Called Creole in New Orleans and Cajun in southwest Louisiana, this cooking was born from several culinary sourcesFrench, Spanish, German, African, Caribbean, and Native Americanyet it is very different from each one. Despite its unusual characteristics, it is a regional American cuisine now known throughout the world. Of all the Creole-Cajun dishes, gumbo is the most representative. It is a soup made from a myriad of ingredients that must be well-seasoned. This book aims to show cooks how to do just that.

To understand the distinctions of Creole and Cajun cooking, it helps to know about the people who invented it. The first French and French Canadian settlers arrived in New Orleans in the early 1700s, followed shortly by ships carrying enslaved Africans through the Caribbean region. Germans settled forty miles upriver from New Orleans a few years later, and within forty years, Spanish had gained control of the colony. Meanwhile, international cooking styles began to merge, along with those of Native Americans. German farmers not only supplied the city with produce and meat from the upriver parishes known as the German Coast; they also became the citys bread bakers. Their product was called French bread, but Germans had the monopoly on baking it, and some of their bakeries still survive today. Then, in the late 1800s, Italians poured into New Orleans from Sicily, creating many of the citys early grocery stores and restaurants and having a major influence on the cuisine. To this day, neighborhood restaurants throughout New Orleans advertise seafood and Italian as their fare.

In the mid-eighteenth century, a large group of descendants of French colonists, known as Acadians, were expelled by the British from Nova Scotia and surrounding areas, partly because they refused to take an oath against France. Following Le Grand Drangement, or the Great Expulsion, many eventually found their way to southwest Louisiana and became known as Cajuns, a derivative of the word Acadians. The deportation was memorialized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his epic poem Evangeline.

New Orleanss earliest foreign settlers were French and French Canadian, whom the Spanish called Criollo. The French translation was Creole, and the definition of Creole has evolved over the years. The Spanish first used the term to refer to the Frenchborn in New Orleans. Later it was used for both French- and Spanish-born in Nouvelle Orlans. Those originating in the Old World were simply called French or Spanish. It was the Creoles themselves who first applied the term to persons of color. They used it to describe their property, much as we use the term domestic versus imported to specify local origin. Creole became an adjective for food and other things.

When the French arrived in New Orleans, a neighborhood was soon created on the Mississippi River overlooking a ninety-degree turn of the roaring river at its deepest point of 200 feet. It was called the Vieux Carr or French Quarter, and at its heart was the French Market. Early in the morning the market became the busiest place within hundreds of miles, bringing together farmers from upriver and fishermen from the bayous, Lake Pontchartrain, and the Gulf of Mexico. They bartered succulent oysters, fresh fish and shellfish, live poultry, and meat from farms west of the city. Produce that thrived in the warm, humid climate filled many of the stands. It wasnt long before restaurants opened alongside the market to feed the vendors as well as the travelers to the market. Some of the cooks in these restaurants were wives of vendors who helped establish a draw of visitors to New Orleans from far and wide to taste their unique style of cooking. The renowned Madame Elizabeth Begue and others created legendary dishes that attracted gourmets across the country as well as farmers across the street. In the late nineteenth century, her fifty-item Bohemian breakfast including wine cost $1.

Within the first decade after the citys founding in 1718, more than 5,000 enslaved Africans arrived in New Orleans. They brought to the port of New Orleans barrels of rice that became the most successful food crop to be cultivated in the new location, as well as okra, peas, beans, and yams. Much came from western Africa, while some was loaded up in the Caribbean Islands, where ships stopped for refreshment and supplies. Among the Caribbean contributions were a variety of spices. New arrivals in the 1780s broadened the scope of African influence, helping to build the French Quarter and farm the rice and sugar plantations along the Mississippi River. African cooking, and to a lesser degree Caribbean, is a major thread in the quilt of southern cooking. Its influence contributed heavily to the staples of Louisiana cooking as we know it today in dishes such as gumbo, jambalaya, and red beans and rice.