Once upon a time a 14-year-old boy caught a perch in a lake near Bishops Lydeard in Somerset. It was late summer, early autumn. There were blackberries in the hedgerows and beechnuts underfoot. In his tackle bag the young angler had a loaf of stale bread from the Golden Hill bakery in Wiveliscombe. This he soaked in water to make small pellets of bread paste for bait. He had cycled 12 miles from before dawn to be at the lake at sunrise. By noon his keep net contained six perch, one crutian carp and two small tench.

Contented, he opened the saddle bag on his bicyle to take out the sandwiches that his father had prepared. The thermos flask of coffee was there with a twist of blue sugar paper with sugar inside, but not the sandwiches. He had forgotten the picnic, but he did have a packet of 10 Nelson filter-tipped cigarettes and a box of Swan matches.

With his sheath knife, he scaled, de-finned and gutted a couple of perch. He cut some twigs from a tree and made things that later in life he discovered were kebab sticks. He picked blackberries and shelled beechnuts and stuffed them into the soaked stale bread, then he formed the bread into patties and toasted them over a fire of pine cones. He speared the fish on the twigs and sat cross-legged as he held them over the fire until they were cooked. With his hands, he ate the scorched fruit-and-nut-stuffed bread patties and succulent morsels of barbecued perch.

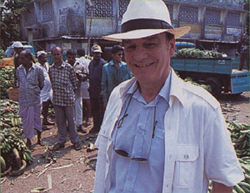

A hundred years later, by the most bizarre route, that boy became a restaurateur and what is obscenely called, not only obscenely but totally without justification, a television celebrity chef. Over 16 or 17 years he travelled the world, eating, cooking and learning, watching the legs being ripped off live frogs in a Singapore market, drinking the blood and the still-pulsating heart of a cobra in Vietnam, cooking salmon fishcakes wrapped in pigs caul in Northern Ireland, staring at the Southern Cross in the top end of Australia, eating ribs of beef and living in fear of being bitten by a king brown (one of the worlds most poisonous snakesAustralia has eight out of ten of the most poisonous ones). He cooked pasta in Bologna, couscous in Morocco, moussaka in Greece, jambalaya in New Orleans, paella in Spain, bouillabaisse in France, dumplings in Prague, goulash in Budapest, puffins in the Arctic Circle, bear on the Russian border, carp in Czechoslavakia, hogs pudding and lava bread in Wales, salmon and haggis on the banks of the river Tay, Nile perch stuffed with raisins and nuts in Luxor, and freshwater crayfish cooked in beer in Sweden on a mad midsummer night. He prepared tom yang kum in Bangkok and beef rendang in Kotabura in Malaysia, stewed wildebeest in a poiki pot in Zambia, cooked cakes and schnitzels in Vienna, cooked pigs trotters (crubeans) and bacon and cabbage in Cork city, and the rest and more.

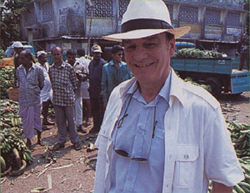

Weary of airports and hotel lobbies, taxis and studios, absurd locations and television directors, producers and book editors who know absolutely bog all about the subject (except that it is popular)[not us, surely? Eds], this boywho is now a man but still remembers being 14 and remembers the words of Confucius, Give a man a fish and he will live for a day, teach a man to fish and he will live forever'has had enough. He decides to move to the Mediterranean, where the olive, the lemon, the tomato, the aubergine and the wine are the jewels in the glittering culinary crown. Then, one fine day, he gets a fax, Go and do a series on India', it says. I dont know anything about India', he replies. Dont worry', they say. We will send you all the information. All you have to do is pop on to a plane and get cooking. And so they did. The facts as presented to me by Nick Patten, my director, and my esteemed researcher, Raj Ram, I have incorporated into my letter from India that starts on page 12.

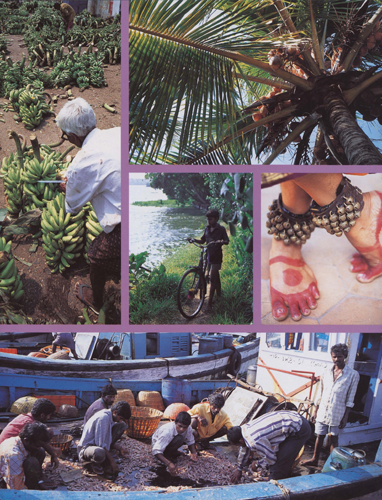

The big orange sun is rising slowly, illuminating the hazy morning as the plane begins a series of long, slow, gentle swoops downwards to Cochin airport in the southern Indian state of Kerala. Endless coconut plantations shimmer grey-silver, slate and green as the sun washes through whisps of cloud and beams on endless meandering waterways, alternately gold and silver, stretching far away. On the slopes there are coffee and tea plantations. Whitewashed colonial Portuguese or Dutch churches are scattered in clearings. Neat villas and verandahed farmhouses pop up in shafts of bright sunlight. Cows, bullocks and goats wander across extinct dried-up deltas that criss-cross the verdant landscape. The twisting waterways and lagoons give way to huge wide rivers and estuaries. Big rusting ships glide lazily along, while all manner of brightly coloured ferries, fishing boats and traditional craft, lanteen-rigged, double-ended, high prows and sterns sweeping up like a cobra poised to strike, sail serenely, outrageously overladen with mountains of hay or sculpted pyramids of coconuts, precariously but precisely stacked, edging steadily into harbour.

As the plane sweeps low over the water for its final approach, I can see loincloth-clad, sinewy men throwing big circular nets from the tiny narrow canoes under the long concrete bridge that the spans the mainland and Willingdon Island. The bridge is teeming with pedestrians, turmeric-coloured tuktuks and brightly painted, overladen trucks piled high with hessian sacks of rice and pepper, coconuts or bananas. On top of their cargo, their backs to the oncoming traffic, sit the workers, huddled against the morning smog and dust, their mouths wrapped in bright bandannas.

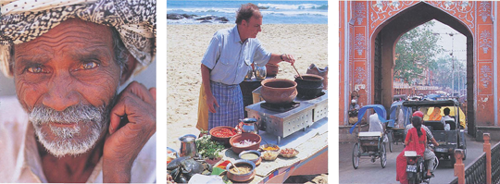

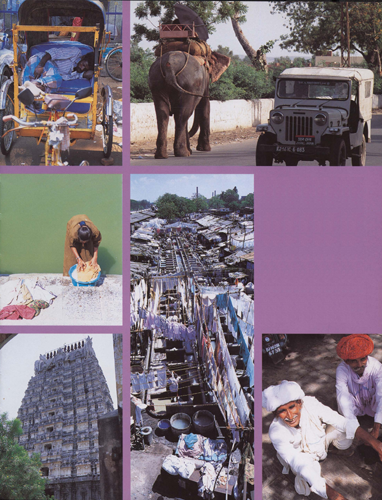

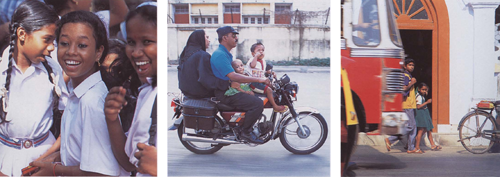

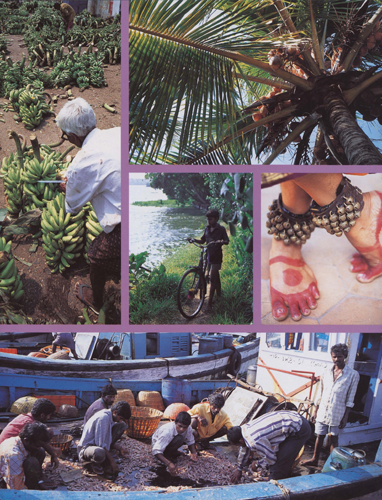

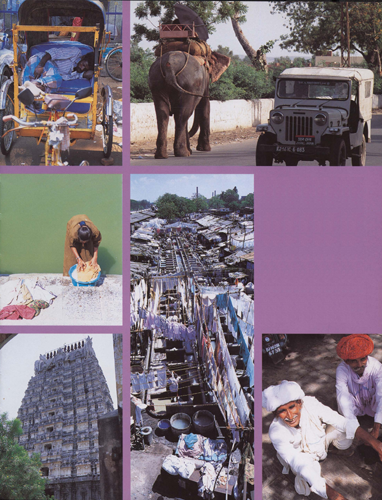

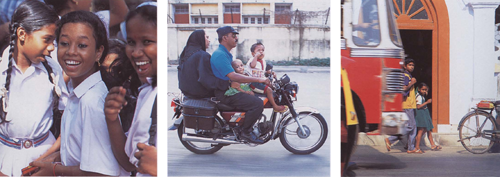

Images from Kerala.

Even at this early hour, the air is hot and slightly choking as we walk across the tarmac of the neat yellow airport. The runways are fringed with coconut palms and, although quite new, the airport buildings have the quaint, unhurried air of a genteel colonial outpost.

You present papers, tickets, passport and boarding cards several times to officials, soldiers and policemen. They are polite, insistent and bewildering. Behind the barrier in the baggage hall, hotel touts, porters, relatives, more soldiers, taxi drivers, nuns, hippies and beggars jostle. In the confusion I am met by two, but rival, chauffeurs, each sent by a different company to pick up Tess, my wife, and me and our 12 pieces of luggage. A polite man in a safari shirt and pressed chinos, carrying a clipboard and briefcase, settles the dispute, I think! But do I pay him too?