Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Blue Rider Press is a registered trademark and its colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC

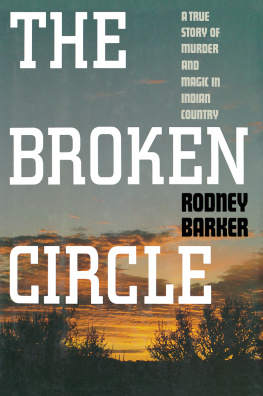

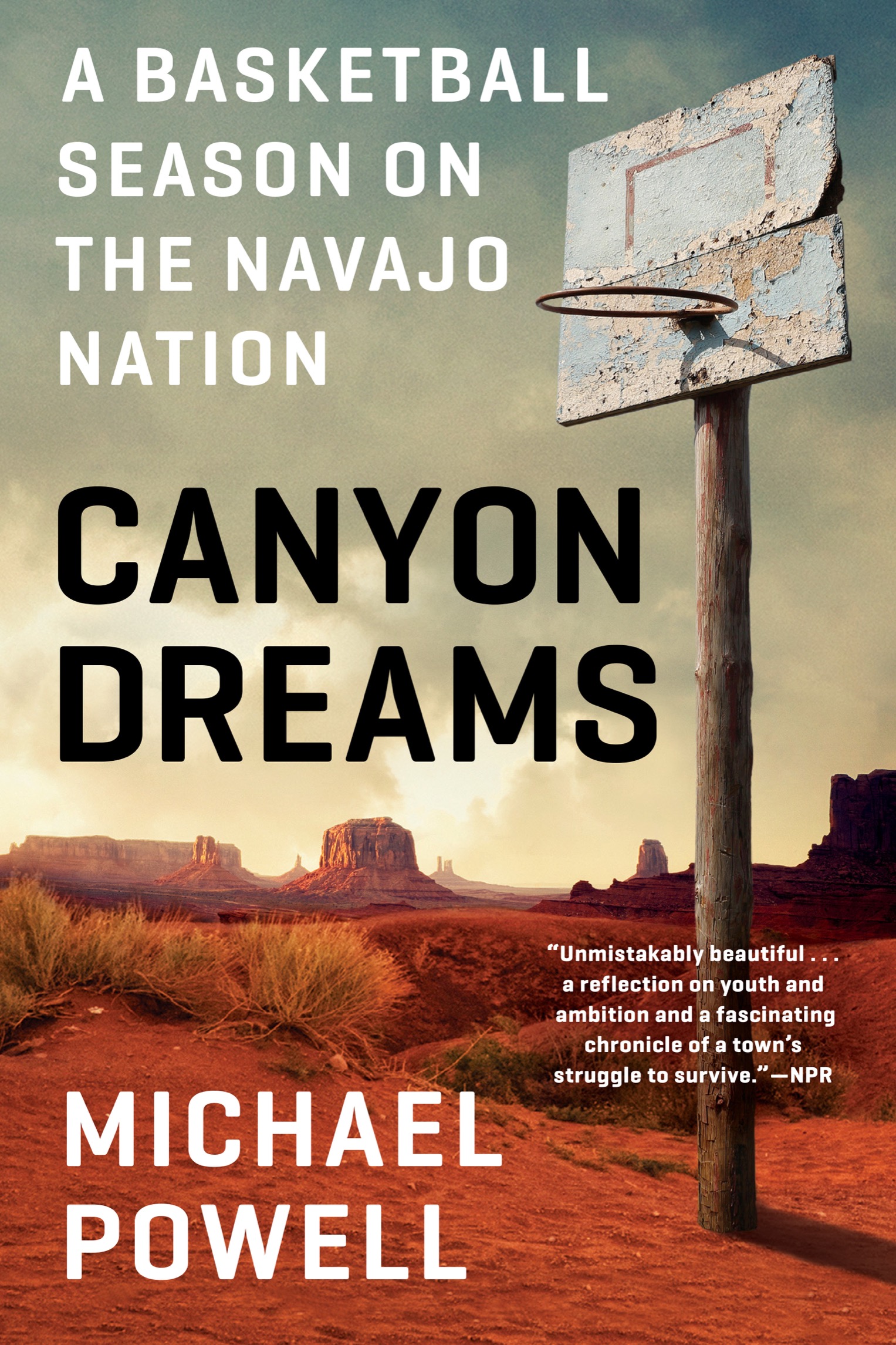

Cover design: Steven J. Meditz

Cover photographs: (basketball hoop) iStock / Getty Images; (background) E+ / Getty Images

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

CHAPTER ONE

The sky was milk white and vaulted. A squall tugged at the creosote and sagebrush and sent dust devils spinning off the mesas. Millennia of rain and Holy Wind, the Nichi Diyini had carved the washes and gulches and canyons that folded into the skin of this land.

To survey this world in the chill of November was to feel loneliness crawl into your bones. There were few creatures and fewer souls.

A distant clanking: A school bus rounded a bend and bounced down a pockmarked old Indian route past red-ribbed buttes that reared out of the earth like primeval monsters. It crossed a creek and passed a wickered grove of cottonwoods, the silver branches delicate as veins against the sky. The road heaved up and up again, and the bus emerged from a gap in an escarpment into a parched emptiness of plain that stretched to the end of vision.

The teenage boys on the bus called to one other and craned their necks and pointed at a red-tailed hawk riding the currents of approaching winter.

A painted black-and-gold wildcat with pronounced claws and fangs stretched the length of this bus, which carried Navajo boys and girls from Chinle to their season-opening basketball games. They were among the more talented players on the reservation, and this was the beginning of their quest for a state championship. The seating hierarchy was as formalized as that of a royal court. Raul Mendoza, a four-decade-long coaching force on the Navajo reservation, married to a Navajo woman yet not Navajo himself, respected although perhaps not beloved, commanded the front seat and stared impassively through dark sunglasses at the gray and rutted road. He had lived a dozen lives in seventy years of wandering. His black leather shoulder bag carried his whiteboard, his scouting reports, and a dog-eared black Bible into which he talked softly at night.

The girls coach was a former rez ball star and a mother. She sat behind Mendoza. Girls basketball games draw thousands of fans on the rez. The male assistant coaches sat behind herLenny, Bo, Julian, and Nedbig men with broad shoulders, all former hoop stars in an unspoken competition to take the helm when old Mendoza retired or got fired. The end can come suddenly in the high desert.

Teenage girls occupied the next block of seats, chatting and laughing and singing to Beyonc. They knelt on seats and on the floor and braided one anothers brown hair. The boys commanded the back of the bus and slouched like cats, heads and arms on each others shoulders and backs. Some tapped out texts to buddies or girlfriends. Some listened to hip-hop on earbuds, and some stared out the window as their land, the vast Dintah, rolled past. Two freshmen boys, awkward fawns, had made this team and they peered, eyes wide and furtive, at the seniors, at the coach, at the girls.

All were excused early from class for the three-hour drive from Chinle, their windswept town at the sandy mouth of Canyon de Chelly, to Snowflake, a Mormon outpost on the arid plains 130 miles south.

Good luck, teachers said.

Get a win, friends said.

Play hard, parents said.

All translated into an unspoken command: You better not lose.

There was no grander sport on the reservations of the Southwest than rez ball, a quicksilver, sneaker-squeaking game of run, pass, pass, cut, and shoot, of spinning layups and quick shots and running, endless running, with an athleticism that found its origin in that Native American time before horses. Navajo learned basketball in Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools but long ago made it their own, a game played by grandparents and parents and children, men and women alike. Play was swift and unrelenting as a monsoon-fed stream. Custom dictated that players help their opponents to their feet. They as quickly knocked them down again.

Chinle High School was the largest school on the Navajo reservation. There have been many fine Wildcats teams but never one good enough to win a state championship, and the collective hunger to claim that trophy was insistent, immutable, an ache. Four thousand people live in Chinle, and on midwinter nights five thousand crowded into the Wildcat Den for big games. On the third day of basketball tryouts in early November, Mendoza waved a milling group of tryouts over to the baseline and asked: What is your goal? To get your name in the Navajo Times?

He did not wait for their answer. He had bidden goodbye to his wife for five months, and he would work every morning, afternoon, and night during the season. He would review game tape until his eyes became red and his vision grew blurry and indistinct. My goal, our goal, he told the boys, is to win a state championship. He held up his right hand and the finger with his fat state-championship ringhe was the only living coach on the rez to own oneand let the boys gawk.

I want to get a bigger ring than this.

These teenagers were perched on that precarious cliff wall between adolescence and manhood, hand- and footholds uncertain. Soon enough they would face a primal decision: Should they leave their land, the largest and grandest Indian nation in the United States and the Navajo world of sacred peaks and spirits and clans? If they departed, if they entered college in the world of bilaganas, the whites, could they survive? If they thrived, could they ever truly return?

Hey, hey, listen to thisblunt time!

Angelo Lewis, Shlow, known as Big Daddy to the little kids who liked to scale his shoulders and back before games, was Chinles big man, the center, a broad-shouldered six-foot-three junior with a perpetual half grin. He showed teammates his cell phone with a Facebook post of a black dude smoking a cigar-size blunt. Angelo was a wiseacre with a feel for the comedy of life and a sarcasm that could crack up teammates. He skipped classes, and sometimes struggled with grades, more from inattention than lack of comprehension. He should have been a senior this year, just like his friends and summer basketball buddies.