E NGLAND

Happy Christmas!

Some say that ever gainst that season comes

Wherein our Saviors birth is celebrated,

The bird of dawning singeth all night long:

And then, they say, no spirit dare stir abroad,

The nights are wholesome, then no planets strike,

No fairy takes nor witch hath power to charm,

So hallowd and so gracious is the time.

W ILLIAM S HAKESPEARE , H AMLET , A CT 1, S CENE 1

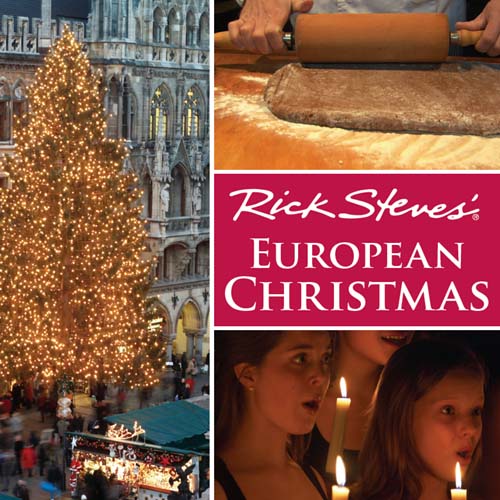

An Elizabethan Christmas

Many of our classic Christmas traditionsholly, mistletoe, caroling, and the Christmas feasthave been celebrated in England for centuries.

In England, the Christmas season, or Christmastide, lasts from December 24th to January 6th, Epiphany. During the time of Queen Elizabeth I (15331603), Christmastide was celebrated with an extravagant hospitality that extended to the whole householdwhether manor, village, or court. The wealthy loaded their tables with all the meats and mince pies they could afford and invited everyone to the partyfrom aristocratic families and courtiers to the lowliest workers.

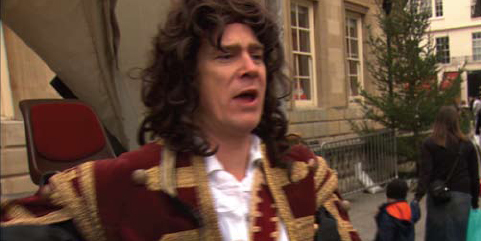

Christmastide began by crowning a master of ceremonies for the Twelve Days of Christmasthe Lord of Misrule, often a student or beggar. The Lord then chose his Court of Misrule, usually eager partiers, to help him manage his unruly businessfeasting, games, and dancing. During these topsy-turvy times, the poor descended on the rich, demanding their best food and drink. If owners failed to comply, they were terrorized with mischief. Christmas became the time of year when the upper classes could repay their (real or imagined) debt to society by entertaining less fortunate citizens.

The festival raged into the New Year. Despite some religious holy days, the celebration was quite secular, featuring masked balls, plays, dancing, eating and drinking, gift-giving, gambling, lots of cards, and general carnival-like craziness. It culminated with the biggest bash on January 5th, the Twelfth Night.

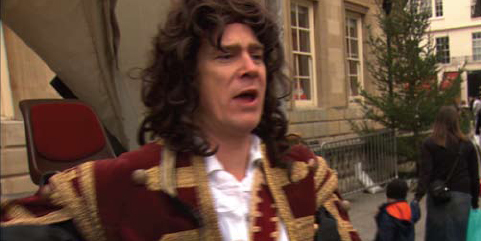

As in Elizabethan times, Christmas today can be a bit raucous and unruly.

Christmas Caroling

The joy of Christmas poured out in song. The caroling season traditionally stretched from St. Thomas Day (December 21st) to Christmas morning. In medieval times, carols were not just songs but also folk dances, performed by wandering musicians accompanied by singers. Considered a pagan holdover, carol singers were banned from church, so instead theyd go door to door visiting the homes of the big shots, performing in hopes of getting a coin, meal, drink, or Christmas treat.

The spirit of an English Christmas abides in song, and even today, towns everywhere are alive with music. From street-corner buskers to sublime choral groups, the English sing their hearts out at Christmas.

Fun and Games

Elizabethans loved to play games, especially at Christmas. Here are a few of their favorites:

Snapdragon:

Players take turns picking raisins out of a dish of flaming brandy and popping them into their mouth. Ouch! Players bet on each others chances of success.

King of the Bean:

On Twelfth Day a bean is baked into a cake. Pieces of cake are distributed among the children and servants. The lucky one who finds the bean is pronounced King of the Bean, and reigns supreme for the rest of the day and night. Sometimes a pea is used as well, and whoever finds it becomes the Queen of the Pea.

Fortune-Telling:

On Christmas Eve young girls try to divine which one of them will get married first.

The Twelve Days of Christmas:

Its thought that the Christmas carol starring a partridge in a pear tree originated with a memory game played on Twelfth Night. Each player sang a verse in turn, adding a new gift while trying to remember all the earlier ones as they sang their way through the list.

Feasting

In about 1570 a proper English Christmas feast was described in this way:

Good husband and housewife, now chiefly be glad,

Things handsome to have, as they ought to be had.

They both do provide, against Christmas do come,

To welcome their neighbors, good cheer to have some.

Good bread and good drink, a good fire in the hall,

Brawn, pudding, and souse, and good mustard withal.

Beef, mutton, and pork, and good pies of the best,

Pig, veal, goose, and capon, and turkey well drest,

Cheese, apples, and nuts, and good carols to hear,

As then in the country is counted good cheer.

What cost to good husband, is any of this?

Good household provision only it is:

Of other the like, I do leave out a many,

That costeth the husband never a penny.

T HOMAS T USSER

The high point of Christmastide was the feasting, which in part served as a reminder that the ever-present threat of hunger had been triumphantly overcome. One notable Christmas celebration was rumored to have featured a giant 165-pound pie that was nine feet in diameter. Its ingredients included two bushels of flour, 20 pounds of butter, four geese, two rabbits, four wild ducks, two woodcocks, six snipes, four partridges, two curlews, six pigeons, and seven blackbirds.

With as many as 24 courses, guests could count on traditional goodies such as mince pies, frumenty (sweet, spiced mush), plum pudding, and humble pie. Humble (or umble) pie was made from the humbles, or innards, of a deer. While the lords and ladies ate the finer cuts, servants baked the humbles into a pie for themselves. And plum pudding had nothing to do with plums. It was a mixture of suet, flour, sugar, raisins, nuts, and spices tied loosely in cloth and boiled until the ingredients were plum, or swollen enough to fill the cloth. During the Puritan reign, plum pudding was deemed sinfully rich and outlawed.

The sweetmeat or dessert course allowed a host to show off his wealth and statusclassic conspicuous consumption. Sweetmeats decorated with crystallized fruits and gold leaf made a splendid presentation. Sugar, which was expensive, was a featured ingredient. The mistress of the house tried to dazzle the guests with her culinary wit and artistry. Creative cooks were especially fond of a concoction of egg, sugar, and gelatin, which they could mold into almost any form imaginable.

Mince Pie

In Britain, eating mince pie at Christmas dates back to the 16th century, or earlier. Some believe that the idea originated with the gifts that were brought to baby Jesus. Its not too hard to imagine dried fruits, nuts, and spices being presented to the child, alongside gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

In the Middle Ages, a mince pie was made in a big dish and called a Christmas pye. A standard pye recipe called for a most learned mixture of Neats-tongue (ox tongue), chicken, eggs, sugar, raisins, lemon, and orange peel, various kinds of spicery

Eventually, little tarts in the shape of a cradle took the place of the great big pie. Sometimes a small figure was tucked underneath the crust to represent the baby Jesus. By the 16th century, mince or shred pies (a reference to the shredded meat that was mixed with chopped egg and ginger) had become a Christmas specialty. Over time the recipe was fancied up with dried fruit and other sweets, and by the 17th century, the filling closely resembled todays mix of suet, spices, and dried fruit steeped in brandy.