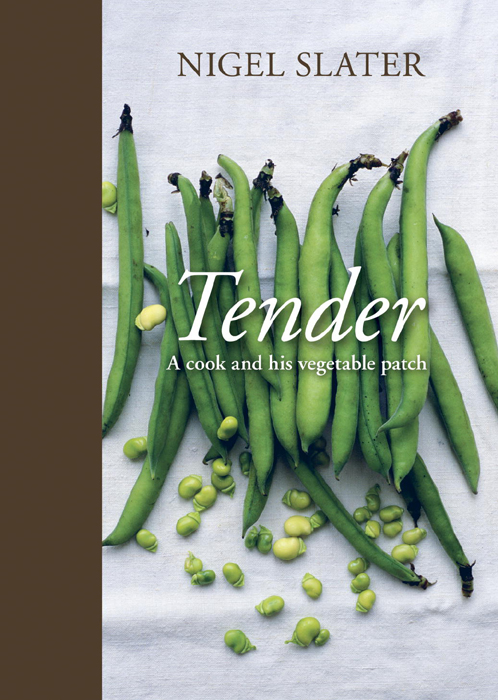

Copyright 2009 by Nigel Slater

Photographs copyright 2009 by Jonathan Lovekin

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Fourth Estate, a division of HarperCollins Publishers, London, in 2009

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher.

eISBN: 978-1-60774-040-7

Cover design by Colleen Cain

v3.1

For Allan Jenkins

To Louise Haines, for her tireless encouragement, support, and patience. I can never, ever thank you enough. To Jonnie for his pictures and friendship, to Sam Wolfson for her brilliance, and to Jiri Merka for all his hard work.

To the wiser and more experienced gardeners whose words I turn to for enlightenment: Beth Chatto, Joy Larkcom, Carol Klein, Jekka McVicar, Sarah Raven, Chris Young, Charles Dowding, Christopher Stocks. To Monty Don and Dan Pearson, without whom this garden would still be a backyard. And thank you too to Huw Morgan; Katie Findlay; and to everyone at The Royal Horticultural Society and The Garden.

To Jane Scotter, who knows more about growing vegetables than I ever will. Thank you for your beautiful produce, much of which is pictured here in these pages and has become so much a part of my cooking life. Thank you too to everyone at the magical place that is Fern Verrow.

Gratitude is also due to: Jane Middleton, Araminta Whitley, Rosemary Scoular, Victoria Barnsley, John Bond, Julian Humphries, Michelle Kane, Graham Cook, Elizabeth Woabank, Sarah Randell, Mark Adderley, Nadia Sawalha, Tim dOffay, and to Allan Jenkins, Nicola Jeal, Caroline Boucher, and everyone at The Observer. To Franco Chung and Rob Watson for their technical expertise and to Dalton Wong and James Duigan for helping me feel better than I have ever done in my life. And an enormous shout to all those kind, generous, and communicative readers whose thoughtful words keep me going.

This book is what it is because of you all.

Introduction

I keep lists. Some copied into notebooks in neat italic script in blue-black ink, others scribbled almost illegibly in soft pencil on the back of an old envelope. Most remain in my head. There is the usual inventory of things I need to do, of course, but also less urgent lists, those of books to read or read again, music to find, plants to secure for the garden, and letters to be written (few of which will ever see the light of day). One list that has remained in my head is that of favorite scents, the catalogue of smells I find particularly evocative or uplifting. Snow (yes, I believe it has a smell), dim sum, old books, cardamom, beeswax, moss, warm pancakes, a freshly snapped runner bean, a roasting chicken, a fleeting whiff of white narcissi on a freezing winters day.

High on that list comes cress seeds sprouting on wet blotting paper. It is a smell I first encountered in childhood, a classroom project that became a hobby. Cool and watery, fresh yet curiously ancient, as you might expect from a mixture of green shoots and damp parchment, it has notes of both nostalgia and new growth about it. Sometimes, when I have watered my vegetable patch late on a spring evening, I get a fleeting hint of that scent. A ghostlike reminder of how this whole thing started.

I guess I have always grown something to eat: that cress on a blotter when I was still in short pants; beans in a jam jar; carrots and candytuft in a forlorn strip of my parents garden. There were the tomato plants precariously balanced on the window ledge of my student digs, orange and lemon seeds and other unmentionable plants nurtured under grow lights, salad sprouters, a bucket garden on a balcony. Then there were the herbs in pots that lethally adorned the fire escape of my first apartment and its communal garden. That I would one day turn my own lawn into a vegetable patch was, I suppose, inevitable.

Perhaps because I was brought up on frozen peasthey were virtually the only vegetable that passed my lips until I was in double figuresI now have a curiosity and an appetite for vegetables that extends far beyond any other ingredient. Shopping at the market on a Saturday morning, I will spend four or five times as long choosing my beans, tomatoes, or lettuces than I will buying anything else. Vegetables beckon and intrigue in a way no fish or piece of meat ever could.

The beauty of a single lettuce, its inner leaves tight and crisp, the outer ones opened up like those of a cottage garden rose; the glowing saffron flesh of a cracked pumpkin; the curling tendrils of a pea plant; a bunch of long, white-tipped radishes; a bag of assorted tomatoes in shades of scarlet, green, and orange is something I like to take time over. And not only is it the look of them that is beguiling. The rough feel of a runner bean between the fingers, the childish pop of a pea pod, the inside of a fur-lined fava bean case, the cool vellumlike skin of a freshly dug potato are all reason to linger. And all this even before we have turned the oven on.

Their beauty and tactile qualities aside, what you do with them is loaded with even greater sensual pleasure. Just listen to this: a supper of golden pumpkin with a crisp crumb-crust flecked with parsley and garlic; a dish of emerald cabbage leaves with shards of sizzling ginger; a crumbling soft-pastried tart of leeks, cream, and cheese; a bright carrot chutney on a mound of ivory-colored rice to make your lips prickle. Soporific risottos of asparagus; gratins of potato, garlic, and cream; yellow tomatoes with a sauce the color of terra-cotta that makes your mouth tingle with chile, lemongrass, and fresh mint. None of this is difficult, time-consuming, or expensive. It is straightforward, approachable cooking for eating either for its own sake or on the same plate as a piece of meat or fish.

While still enjoying my crackling pork roasts and grilled lamb, my baked mackerel and crab salad, I have become more interested than ever in the effect of a diet higher in greens than it is in meatboth in terms of my own well-being and, more recently, those implications that go beyond me and those for whom I cook. As Michael Pollan, author of In Defense of Food (The Penguin Press, 2008), says: In all my interviews with nutrition experts, the benefits of a plant-based diet provided the only point of universal consensus. On a personal note, I would simply say that I feel much better for a diet that is predominantly vegetable based.

![Nigel Slater - A Cooks Book: The Essential Nigel Slater [A Cookbook]](/uploads/posts/book/441033/thumbs/nigel-slater-a-cook-s-book-the-essential-nigel.jpg)