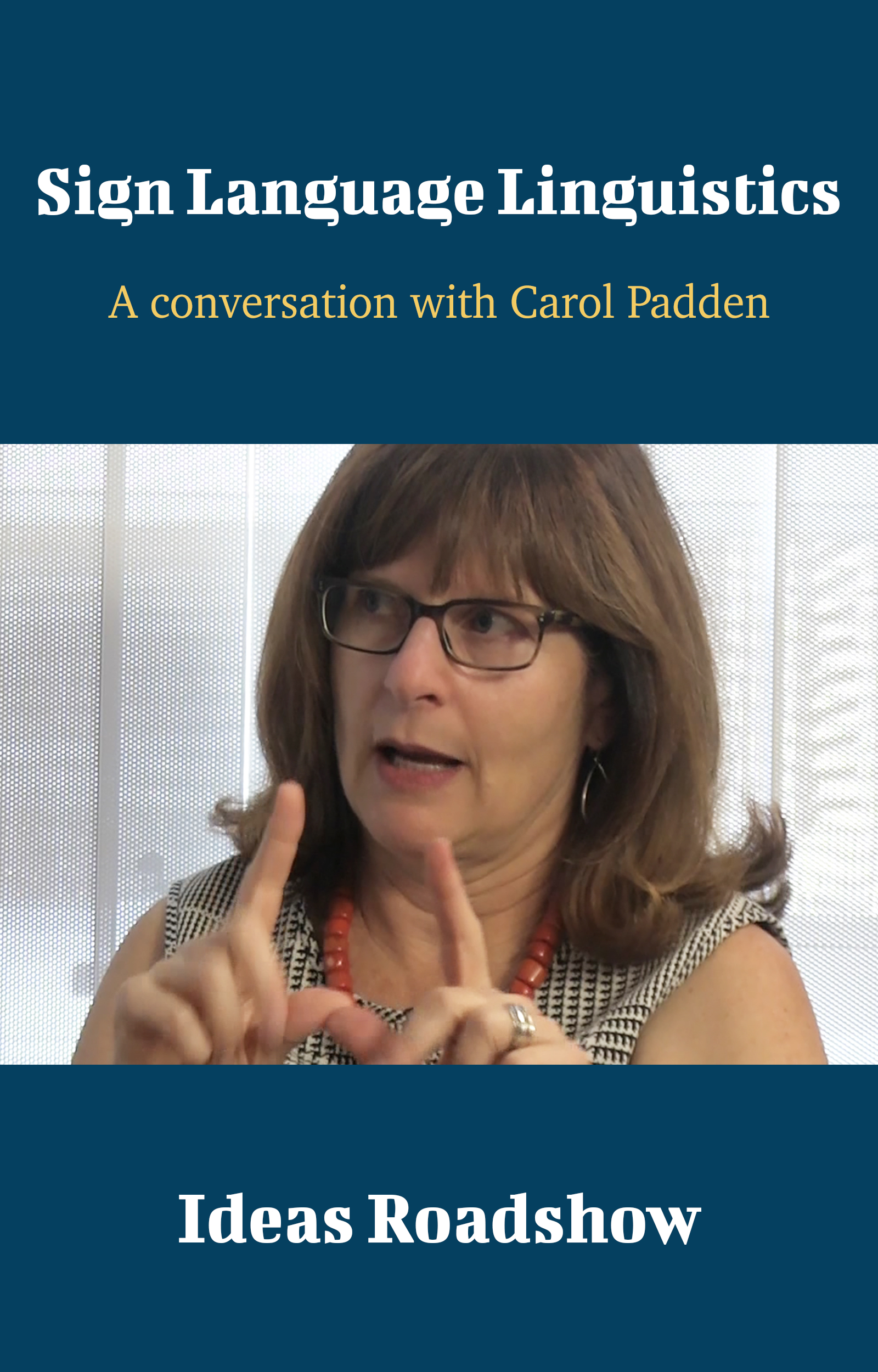

The contents of this book are based upon a filmed conversation between Howard Burton and Carol Padden in San Diego, California, on September 25, 2014.

Introduction

Heeding the Signs

What makes a language a language?

Simple, right? Any time a group of humans get together and use a collectively-recognized series of utterances to successfully communicate ideas and concepts, weve got ourselves a language.

Well, sort of.

What if I gesture to a stranger in a distant land about locally available food options? We might be communicating, somehowalbeit crudelybut few would mistake what were doing as exercising any genuine language.

And what if I spend an afternoon poring over a Latin or ancient Greek text, or trying my hand at deciphering some ancient hieroglyphs? Nobody pronounces these sorts of utterances any morein fact, we might not even know what the correct sounds arebut that hardly denies the linguistic status of those marks on paper.

And then there is the question of American Sign Language and its other geographical signing counterparts. Are they real languages too?

We didnt used to think so. But based upon Bill Stokoes groundbreaking work in the 1960s, we now have a very different and measured appreciation of what, linguistically, sign languages are all about. Although it hardly happened overnight.

Carol Padden, the Sanford I. Berman Chair in Language and Human Communication at UC San Diego, began working with Stokoe as an enthusiastic sophomore in the 1970s. She vividly remembers the widespread reluctance of both the deaf and hearing communities to embrace Stokoes ideas.

I was there almost at the beginning1974it was only about 9 years after Bill had published his dictionary of American Sign Language (ASL), but people thought he was crazy. They thought it was a vanity project and wondered why someone would make a dictionary that had no pictures of signs in it. He had developed a code for the hand shape and the movement because he wanted a phonological, phonetic analysis of how the movements came to mean things.

But deaf and hearing people alike thought it was a fools project, that he was just doing this because he was a little bit crazy. In reality, he was just his own person: he was an independent thinker.

It turns out that Stokoes insights didnt just make us better appreciate ASL, they shed vital light on how to characterize all languages:

He published A Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles, meaning the idea of dividing a sign into multiple parts, not simply examining how it looks.

The same basic hand shape could give rise to very different signsusing a C hand shape, for example, one can sign drink, church and very smart. They have the same concept of the hand shape, but thats the only commonality. So he looked throughout the language and searched for the distinct relevant parameters to characterize meaning.

Not all characteristics are relevant to meaning. In English, for example, he recognized, that th doesnt have any common meaning. Take the words there, wither, and path. The th is the same in all three of those, but the function is different. So he found the different parameters throughout the language and analyzed where a sign was produced. For example, a sign can be produced at the chin, as in drink, or at the forehead, as in very smart. You move the hand shape to different places, which changes the meaning. What type of movement matters as well. So for drink the hand shape goes up, whereas very smart stays on the forehead. Church goes up and down and has a bounce to it, and so forth.

Bill notated and coded those things and put them into a corpus. He didnt include every sign, because the dictionary wasnt big enough for that, but he included a good subset of the signs. That seemed to be a good idea.

But in 1965, people wondered why he would do something like that. They wondered, Whats the point of such a dictionary? Now we understand. The point is that humans build structure: they create words, sentences, clauses, phrasesvery complex entities and utterances.

Now that we have a deeper understanding of what languages are, complete with an explicit understanding of the linguistic complexity of ASL and other sign languages, we are naturally better equipped to compare and contrast them.

And, equally importantly, we are finally in a much better position to appreciate how they came about in the first place.

A key aspect of the development of any languagesigned or spoken Carol realized, was gesture. But for years, gesture was a veritable third rail for sign language linguists, given their natural concern that many would regard all sign languages as just a glorified form of gesture.

When I started, we wanted to keep a distance from gesture, because people would say, Oh, its universal. Its the same thing.

And we would say, No, its not. Its different. One gesture, like thumbs up, can mean a multitude of different things, including: Good job, Its working, See you later, Everythings good, Im fine, You can leave, and so forth.

But in sign language, you would have a different sign for each of those expressions. You have a lot more specificity. You have words that you combine and recombine. So we needed that distance from gesture, because a lot of that work was really looking at co-speech gesture, which is what Im doing right now as Im speaking: Im not signing.

Gesture follows the rhythm of speaking. Sometimes you can use it to refer to the size of something, like by saying something is small, or saying that it was roughly this size or that size. Co-speech gesture is very much linked to what youre speaking. There are lots of ways that gesture seems so different from sign language, and we wanted to emphasize that difference.

Thirty years later, I think weve made our point. Now, what Im doing, together with some of my colleagues, is going back to gesture and thinking about how languages come into being.

Thus equipped, Carol and her colleagues have carefully investigated the advent of new sign languages throughout the world, from Israel to Mexico to sub-Saharan Africa, carefully documenting their distinct evolutions.

You have a community thats closed for some reasonmaybe its geographically distant, maybe its ethnicity, maybe its an islandbut for some reason theyre kept separate from schools, from national sign languages. If you have a mix of deaf and hearing people, they will spontaneously begin to create a new sign language from gesture.