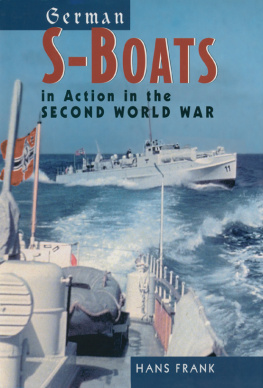

in the Second World War

Hans Frank

TRANSLATED BY

GEOFFREY BROOKS

Copyright Verlag E. S. Mittler & Sohn GmbH 2006

Translation Copyright Seaforth Publishing 2007

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

BarnsleyS70 2AS

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84415 716 7

First published in 2006 as

Die deutschen Schnellboote im Einsatz

by Verlag E. S. Mittler & Sohn GmbH

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and

retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the

copyright owner and the above publisher.

Translated Geoffrey Brooks

Designed and typeset by Sally Geeve

Printed in China through Printworks Int. Ltd.

Contents

Before the First World War, fast motor launches were an extravagance available only to the wealthy few. When steam reciprocating machinery was still a novelty in ships, there were already international competitions for speedboats. When war came, they were found employment from early on as weapons carriers. The most impressive demonstration of what they could achieve was the sinking of the Austro-Hungarian battleship Szent Istvn by an Italian motor torpedo boat in 1918.

A volunteer Motor Boat Corps was formed in Germany, but despite the Kaisers patronage, was never integrated into the naval organisation. Designated LM-boats, the craft were equipped with powerful airship engines and used to remove antisubmarine nets laid by the Royal Navy across the channels used by U-boats leaving their Belgian bases.

On the eve of the Second World War, the S-boats of the Kriegsmarine (designated for uncertain reasons E-boats by the British) were already an obsolescent breed, being the produce of early clandestine moves by individual officers and shipyards to circumvent the Versailles Treaty. Their strategic and tactical role was considered to be that of naval auxiliaries. The new arm of the service, poorly prepared, now took its place in the great confrontation. As with all German units, from the outset too much was expected from too few boats. In the long run, despite outstanding technical improvements and the wiles of their experienced crews, the S-boat Arm was unable to hold its own against Allied defences, whose sheer advantage in numbers, superior electronics and continual aerial bombardment demanded of it too high a levy.

In this fascinating historical account, the author describes the missions, operations and finally the collapse of the German S-boat Arm. The impressive story of human achievement in all theatres is a chronicle of success and failure. The vain hopes of a political leadership vested in the S-boat Arm to the very end could not be, and were not, met.

Professor Peter Tamm

Wissenschaftliches Institut fr Schiffahrts- und

Marinegeschichte, Hamburg

1

Development and First Operations

Three basic factors made the creation of the S-boat Arm possible. First was the torpedo as a self-contained weapon of devastating effect; second, the operational advantage, already recognised by the Torpedo Boat Arm, of high speeds; and third, new engines, allowing the construction of smaller boats.

Germany had played a major role in the development of small, fast boats before World War I, the leader being Lrssen with his round-frame racer Donnerwetter (19059) and the Lrssen-Daimler boat with which he won the 1911 Championship of the Seas at Monaco. The real developments in the fighting role, in which the craft was equipped with torpedoes, were made principally by Italy and Great Britain. Both used small motor torpedo boats successfully in operations. The Italian MAS-boats (Motobarca Armata Svano) achieved a string of successes in the Adriatic against the Austro-Hungarian navy, an example being the sinking of the battleship Szent Istvn by MAS-boats on 10 June 1918. British MTBs were often in action in the Channel against German units. Their successes were few, however, for they had to discharge the torpedo over the stern tail-first. This required high speed to prevent the torpedo catching up. A surprise approach and a sure aim were therefore difficult. In July 1919, however, they proved their effectiveness by sinking the Russian cruiser Oleg at Kronstadt.

The German development followed a different path. Not until the summer of 1916 were small, fast motor launches required, when their task was to clear British anti-submarine nets at Zeebrugge and Ostend and so allow U-boats safe access and departure at these ports. A mix of boats was needed, some to work at the nets, the others to keep the lurking British destroyers and torpedo boats at a safe distance. These guard boats therefore had torpedo armament. In the autumn of 1916 the C-in-C Baltic requested small torpedo carriers for use against Russian naval forces in the Baltic Islands region.

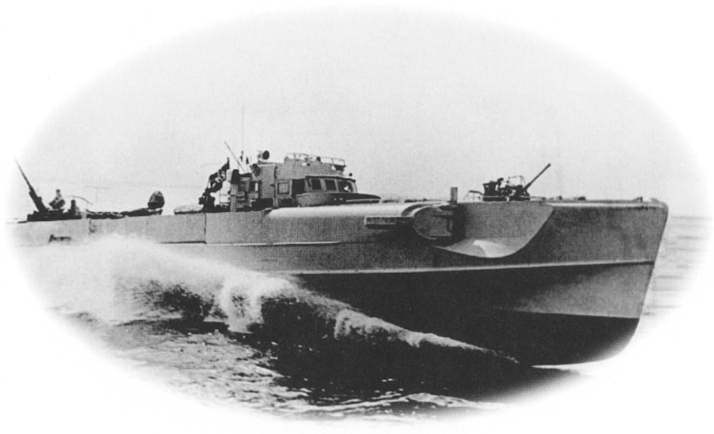

Two net boats and a guard boat (right).

The first six boats were built in 1917 at the Lrssen, Naglo and Oertz yards. They displaced around seven tonnes, were sixteen metres long and with their three Zeppelin airship engines could make thirty knots. Designated LM 1 to LM 6 (LM standing for Luftschiff-Motor), the first four boats were equipped with net cutters; the other two each had a torpedo tube.

After inclusion in the Motor Launch Division, the boats were attached to Naval Corps Flanders. Several skirmishes off the coast of Flanders resulted in only a single success. Later in the Baltic, on 24 August 1917, the 1,200-gross-ton Russian minelayer Penelope was sunk by them in the Irben Strait off the Baltic Islands.

Experiments were run with LM-boats off the Belgian coast using remote control, but these craft were never used operationally. Another fourteen LM-boats were built in 1918 as torpedo carriers; others ordered remained incomplete at the wars end.

Reichsmarine

After the drastic reduction of the fleet by the terms of the Versailles Treaty, Germany was allowed to have six battleships not exceeding 10,000 tonnes, six 6,000-tonne cruisers, twelve 800-tonne destroyers and twelve 200-tonne torpedo boats. German Naval Command directed its efforts to keeping the predominantly old ships in commission and kept a stern watch on the permitted standing force of 15,000 men, bearing in mind the revolutionary confusion of the time.

The Navy had continuing interest in small torpedo carriers, primarily for coastal defence work. For fear that these boats might be considered torpedo boats within the meaning of the Versailles Treaty, the development was kept secret. For this purpose Kapitn zur See Lohmann, head of the Naval Transport Department at the German Admiralty, founded TRAYAG (Travemnder Yachthafen AG), HANSA (the High Seas Sporting League), the Neustdter Slip GmbH and the NAVIS shipping company. From unofficial special budgets, partly from the Ruhr Fund and the funds for war purposes, boats completed during or shortly after the war were bought through NAVIS for extensive trials. In the autumn of 1919, HANSA sailing instructors with military training took over the TRAYAG boats and carried out nautical and tactical exercises, often with naval units.