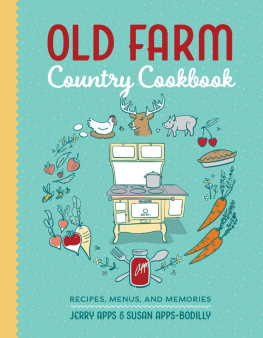

In the late 1930s and 1940s, home cooking was altered forever when electricity and gas became widely available. Rationing during the war years forced home cooks to make do or find substitutes for the foodstuffs they were used to. Social life changed when roads were improved to cope with the growing use of cars and buses, and this enabled rural dwellers to travel to the cities. A demand for houses saw trades develop, and there was a shift in populations as more people sought work in the cities. Country towns shrank.

Men and women returning from war in Europe, North Africa and Asia brought home a broader range of experiences and new ways of cooking. Education and the war work experiences of women opened up possibilities for work beyond the home. Increased prosperity because of good prices for primary produce saw new foodstuffs being imported. And New Zealanders continued to travel and then come home with new skills and ideas as to how to improve their lifestyles.

Food is an important part of every culture. It reflects and affects many areasfrom religious beliefs to health. Sharing food is the best way to celebrate family and friendships at occasions big and small. And, in the sharing, many tales emerge.

The recipes are true to their decade, but in the interests of better eating many have been altered slightly to incorporate modern ingredients, methods and machines. They are recipes I have made or thought about making since I began cooking in the 1950s. Prior to that decade, they are the recipes of my grandmother, aunt and mother.

A cook recalls the good times and bad times of the Depression years

Times were tough, especially for those with no job and a family to feed. But on a high-country sheep runeven though wool prices were low, rabbits were stripping the landscape of anything green, and there was no income to speak ofthere was security: a sturdy house to keep out the harshest winter, wood for fuel, and plenty of food to be hunted, fished, reared and grown. It was a time when practical skills and common sense prevailed. It was a time for making do with what was available. And for sharing everything, no matter how small, with others.

W ILLY and I moved to Clare Burna sheep run that stretched up a valley from the lakeshorein the 1930s. Sadly, we left before any prosperity came our way. It was hard country, and a hard life, but we loved it.

I never went back. Willy was sick, then he died, and suddenly I was very old and lonely. I liked memories better than anything.

There is a red grass that grows along the road verges in the high country. It flowers all summer long and I loved its deep, sweet smell. That and the spicy clove fragrance of briar roses. There were lakeside smells of beech trees, bog myrtle and monkey musk, too, mixed in with the scents of the lilies and lupins from the garden.

There was nothing much at Clare Burn when we moved in. The house was originally a shepherds hutone room, and a bit of lean-to we used for washing and cooking. Willy, with a neighbour to help, added one room at a time until we had a sitting room, two bedrooms and a large kitchen. Part of the kitchen always had its original dirt floor, but the dirt had a lot of mica in it and, as it was packed down hardand I suppose it had been like that for 20 years or so before we moved init looked like polished wood. Or maybe marble, though I have never seen marble floors.

I hooked all the floor rugs myself. Everyone did. We gathered bits of sheeps wool off the fences, and pulled rabbit fur from stinking green skins, spun everything into hanks, then knitted the hanks into strips. Then, just like a rag rug, the strips were hooked through sacking. Goal sacks, sugar bags, anything like that was useful. We never used wool sacks, though. They cost far too much.

The landscape was barren at firstrabbits and deer stripped the bush and brackenbut I planted hundreds of willows and larches. And we had an enormous garden. The soil was glacial silt, and with water and a good layer of manure it could grow anything. I added sheep dags to the mix of horse, cow, chook, pig and sheep droppings, and broke the soil into a fine tilth. We grew carrots, potatoes, beetroot, parsnips, Jerusalem artichokes, swedes, white turnips, marrows, cabbages, cauliflower, silver beet, spinach, beans, peas, asparagus, strawberries and lettuce. A sunny corner was for tomatoes, and the lot was surrounded by low berry hedges: gooseberries and red, white and black currants. I had apple, pear and quince trees, a cherry tree with sour fruit, and a row of plum trees, including one variety I dried and that Willy declared was better than any prune from Australia.

I had a large flower garden, too, and, even if I say it myself, my Christmas lilies were the best for miles around. The scent! I grew Canterbury bells in a big, half-moon-shaped garden, and once a man came and took a photograph of them for the Auckland Weekly.

There was no going to a shop or anything for plants. We sent off for seeds when we had a bit of spare money, but mostly I got seeds and plants from Granny. She was my fathers mother and had a grand reputation as a gardener, a cook, and a dairywoman. I had lived with her before Willy and I married. She had a sort of a hotel down-country. It had a bar and a dining room and a few bedrooms. It was built when a coach used to go over the Pass to the lakes district. Grannys place was the coach stop and she always called it a hostelry (God help anyone who said pub). It had cooking and gardening. I had to help with the milking, too, but I hated that. You spend all your time dodging cowpats, especially fresh ones.

I was good with my hands and nothing was wasted. We never had any children of our own, but my brothers and sister had plenty to share, and every school holidays we had three or four young ones to stay. We had a sort of bunk room up by the wool shed for the shearers and they slept there, and in the summer Willy put up an old army tent hed got from somewhere.

The bus drove up from down-country once a week. It was known as The Coach, as a hangover from the times when it really had been a horse and wagon. It brought up our mail, papers, store-bread, tyres, sheep dip, candles, kerosene, flour, tea, sausages and, occasionally, passengers.

We had no amenities really. No electricity, no water in the house, no flushing toilet. The lavatory was a long-drop, but it sat up on top of a wee rise and it was quite nice sitting up there on warm days looking a telephone bureau which I worked in, but she expected me to help everywhere, which meant I learnt a bit of everything, including over the lake to the grand hills. Not so good in the winter, though. When you wanted water at Clare Burn you went outside, pumped a handle up and down and eventually water gushed from the spout. The kitchen didnt have taps but it had a huge tin sink and very large benches. And an oak gate-leg table that I loved. I polished it so hard with beeswax for so many years that it got a hollow in it. When it was opened up fully it was quite large, but when we had visitors for afternoon tea I folded it up and put a cloth over just the centre bit and it looked like a real tea table.