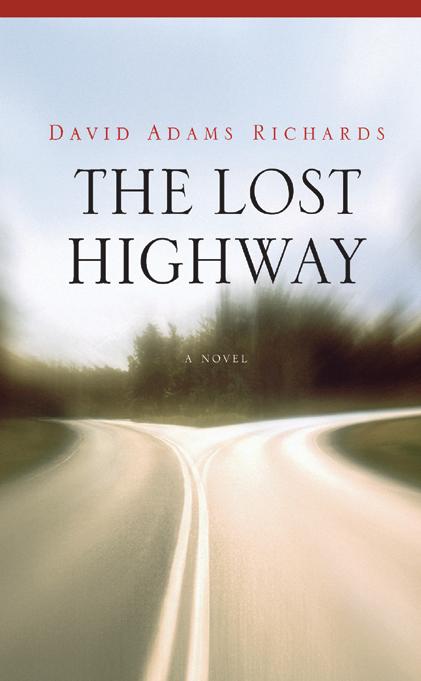

Originally published by:

M AC A DAM /C AGE

155 S ANSOME S TREET , S UITE 550

S AN F RANCISCO , C ALIFORNIA 94104

COPYRIGHT 2007 N EWMAC A MUSEMENT I NC & David Adams Richards.

A LL R IGHTS R ESERVED

C ATALOGING D ATA

ISBN: 978-1-59692-284-6

FOR P EGGY

AND FOR P AT

B URTON T UCKER MOVED TO THE HAYSTACK AND SAT DOWN in the brine of hay, and looked down across the barn and into the open, in the space beyond his house where in the sky was a cloud the shape and color of black gunpowder. The day was still murky and warm, and a feeling of oppressive, ragged heat surrounded him.

What is hidden will be revealed, Tucker said. This is what old Muriel Chapman said to him once when he was visiting her. She had smiled at him, when he said he had no idea what was going to happen if things did not get betterfor now everyone was talking about a big war. And he heard this war would be closer than ever, perhaps as close as Fredericton. They would come in the night, and at night be like thieves. He had been to Fredericton once as a bat boy with a baseball team.

What is hidden will be revealed, she had said, simply. This of course implied nothing or everything depending on how one viewed it, but made her seem very wise to Burton at any rate. And he had heard of both night and nightly thieves from the Bible, which he kept together with his trophies and his pictures in his office drawer.

Mrs. Chapman had, as people said, lived an exemplary life. She did charity work for many people and it was known that she had baked for the community Christmas dinner for thirty-nine years. The problem in her life was her great-nephew Alex Chapman. She gave him everything, went to the principals office in high school, and took up for him. Tried to do this for him, tried to do that.

He had had problems many times in his life, and things did not turn out. He had come home a few years ago, and worked for his great-uncle Jim off and on, disillusioned and ill tempered, for the great turn of events that he had hoped and longed for had not happened to him. Some day, as he often said, or said often enough, these great events would come and he would be recognized.

Then the fools will be sorry, he had said.

Yes they will, Burton said.

The fools will be sorry, Burton.

Im sure of it, Burton acknowledged.

When Alex was young and small, his great-uncle put him to work after school in the junkyard, or back at the pit burning garbage. The boy would go to school, with three feet of snow on the ground, smelling of soot from a fire. Though they had money, the uncle was parsimonious, and sometimes he would clutch a dollar in his hand for an hour before he finally gave it to the boy.

Alex left work, went into study for the priesthood, and then left to wander the world. He went to university and worked with the anti-poverty league. He got very angry, and said things like: Why dont people give it away!

Then, abused and worn out, he came back and tried to fit in. For the last five years he had taught a course on ethics at the community college. He taught it from September to December and was paid $3500. That seemed to get him through the winter if his uncle helped him. Without his uncles help there was no telling what would happen.

Peopleand there are gossips in the worldsaid that for a man who wanted to live like an ascetic, Alex hoped a little too much for some kind of inheritance. But others said he deserved something from his relationship with his uncle, who treated him too harsh for too long. Others, too, said his uncle would never leave him with nothing, that in the end the uncle had always been there for him.

Tucker had thought of Mrs. Chapman all day. The war as yet had not come. But perhaps it would soon. The highway drifted on below his garagedrifted away forever, to the east; a garage so out of the way the company had taken his pumps from him, and he had to make up his lost revenue by giving deals and working later every week. In the lonely, darkening stretch of country road the light of Poppy Bourques sawdust truck could be seen rising and falling though the black, heavy trees. He remembered lights like these on a summer night long ago, when his friends and he came home from baseball games. But his friends eventually outgrew him, and he stayed as he was, with, it seemed, no real prospects or future. He called on them to come over, but after a time they had little to say to him, and got married, and his room filled with mementos from his youth, when they were happy together, did not seem to contain them.

He would go and sit with his cousin Amy, for an hour or two, and they would talk about all her plans that seemed nice and innocent. She played the guitar and had a box of CDs and was the kindest of all to him.

Burton wondered what would happen to the children like little Amy if there was a war. Well, who could say? No one wanted to bomb children. Almost every general said, We are against the killing of women and children, and Burton would say, Thank God, but then they proceeded to bomb them with great aplomb.

Burton was told by some people that he had to stop being so friendly to childrenespecially Amy, who they said now had her own boobsand that many children didnt want him stopping them up on the highway to speak to them as they waited for the bus in the freezing January mornings. That it was a new age, and certainly he had a right to say hello, but there were a lot of mothers and fathers who were suspicious of people like Burton Tucker.

Then the police came one day, and took him asidea young man and woman with blue uniforms and guns on their beltsand told him he shouldnt pick little girls up and swing them around so their underwear showed. The young female officer looked at him with a triumphant smileas if all her life she had wanted to say something just like this. He started to cry as he always did, and told these officers he was an attendant at the open-air rink and at the community center dinners, and to prove this he showed them his hat, much like theirs, that said BURTON on the front.

Later, Markus Paul, the First Nations constable he liked, came in and told him not to worry and that things would turn out in the end, and wasnt the garage a place where everyone gathered, and didnt people look up to him, well there you go.

L AST WEEK B URTON HAD BEEN IN HIS GARAGE, AND THE DOOR was opened and James Chapman came in. He walked now with a game leg and a cane, and his face, which could show almost immediate anger whenever he wanted, was gray. And he didnt like dogs. He asked abruptly for the oil to be changed on his truck, and Tucker did so while Chapman waited in the heat of the office. This was Chapmans roadway, a roadway he more or less thought he owned for the last fifty-five years. But the politics and the times had shifted, and he realized he was forgotten. His business was forgotten, his friends were dead. This had made him take to playing pool every weeknight at Brennens, and having one too many drinks.