First, let me thank all authors who have trod the desert sands before me and to whom I owe a debt; I especially acknowledge all those quoted in the text and thank them for their help. The illustrations are from my own collection and once again I am grateful for the care with which Krisztina Elias has re-photographed them. A big debt of gratitude to Shaun Barrington, my editor at The History Press, and the guiding light in all that I have written.

Omdurman destroyed the power that was Mahdiism, but did not put an immediate end to the Khalifa, or his supporters. This took fifteen more months, during which period further battles were fought, and men died on both sides.

Kitchener was soon steaming up river to deal with the threat at Fashoda. In negotiations with the friendly French Commandant, Jean-Baptiste Marchand, the Sirdar and Wingate were able to reach a stalemate. Meantime, earnest negotiations between Paris and London led to the French backing down; the Upper Nile would stay in the British sphere of influence.

Just five days after Omdurman a force of 1300 men, mainly Egyptian Army reservists, under Colonel Parsons RA, set out from Kassala to occupy the headquarters of the Emir Ahmed Fadel, whose 3000 warriors posed a threat between the Abyssinian border and the Blue Nile. The two sides clashed at Gedaref on 22 September. Parsons won the fight (and a final Victoria Cross of the campaign was later awarded to Bimbashi the Honourable A. Hore-Ruthven, who rescued a wounded Egyptian officer under heavy fire), but was trapped there for several weeks.

A B UREAUCRATIC VC

There was a long debate about awarding a Victoria Cross to Hore-Ruthven after the fight at Gedaref. He was officially Absent Without Leave from his militia battalion in Scotland, was below required officer height and had been applying for a regular commission. After a protracted correspondence it took royal intervention to get Hore-Ruthven his medal.

On 26 December 1898, the emir was forced into a battle at Rosaires on the Blue Nile by another Egyptian force led by Taffy Lewis. The Mahdist defeat came at the cost of an infantry assault; some 500 dervishes were slain, 1700 captured, but Lewis lost over 30 men killed and more than 140 officers and men wounded amongst the 10th Sudanese and his tribal irregulars.

Next it was the turn of the Sirdars brother, Walter Kitchener, to lead an expedition into the blistering wastes of Kordofan. They toiled for two weeks in January 1899, and got to within ten miles of their quarry before it was learned that the Khalifa, far from being supported by 15002000 tribesmen, now had with him an ansar of upwards of 8000 dervishes! Walter Kitchener prudently decided to retire before he became a second Hicks.

Um Dibaykarat

For ten months during the hottest part of the year, the British waited and the Khalifa wondered. Then, in November 1899, Reginald Wingate, commanding his first and only expedition, set out with a 3700-strong column, including the 9th and 13th Sudanese battalions, a squadron of cavalry, 6 Camel Corps companies, a field battery and 6 Maxims to settle matters once and for all.

On 22 November they surprised Ahmed Fadel, with a loss of 400 Mahdist dead, though the wily emir escaped. Next morning a deserter told Wingate that the Khalifa was camped just seven miles away.

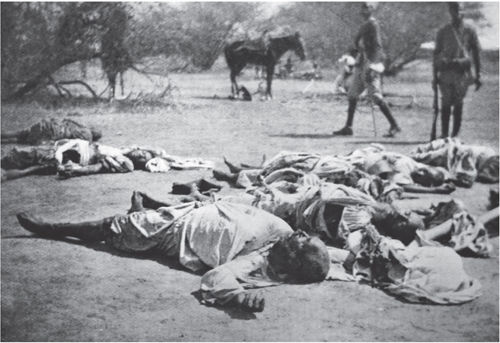

54. Dervish dead at Um Dibaykarat. The man in the centre is the young Emir Ahmed Fadil.

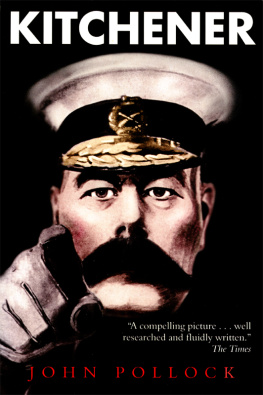

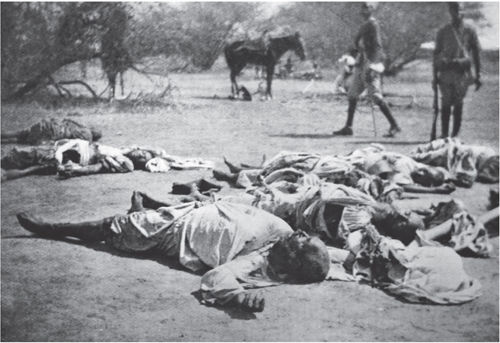

55. The Khalifa Abdullahi lies dead killed by Maxim fire at Um Dibaykarat surrounded by his faithful retinue.

In a classic dawn attack on 24 November the Anglo-Egyptians stormed the Mahdist encampment after it had been raked by artillery and Maxim fire. Realising that it was the end, Abdullahi, who was wounded in the left arm, ordered his emirs to dismount, roll out their prayer mats, face Mecca and join him in worship. Ali wad Helu disobeyed and charged into a hail of bullets. Most of the Khalifas entourage, including Ahmed Fadel, stayed with him to the end and were shot down. One who escaped yet again was the eternally cunning Osman Digna.

Gunner Franks examined the bodies and wrote: I went back to see the Khalifa. In front of him lay the riflemen of his bodyguard, in a double line, evidently killed to a man in their places shooting, each man had shot and shot till he died. A little way beyond lay Abdullahi. He had, thought Franks, quite a nice face, a stoutish built, powerful, elderly gentleman, with a slight grey beard not a bit the cruel tyrant one expected.

British Troops Arrive

By late February 1898 a British Infantry Brigade under Major-General Gatacre had slogged to Berber; it consisted of the 1st battalions of the Warwicks, Lincolns and Cameron Highlanders (all part of the British Army of Occupation in Egypt), supported by Royal Artillery (including six Maxim guns), and a company of Royal Engineers. Fresh from Malta, the 1st Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders joined the brigade after a short spell in Egypt.

Perhaps to prove himself a fighting commander and impress Kitchener, Gatacre led his men on the last leg to Berber by a forced march across the desert. The troops set off on 26 February and arrived on the morning of 3 March. It was so tough that some men fell asleep marching, others had no skin on their feet and several fell out with sunstroke. Egyptian bands played them into Berber and regiments lined up to cheer. Lieutenant Cox of the Lincolns had seven blisters on his feet and felt the mens confidence in Gatacre was shaken He has the reputation of wearing out his troops unnecessarily.

During December 1897 and January 1898 the great war drum had boomed out across Omdurman and councils were held late into the night. The Khalifa Abdullahi talked of jihad, spurred on by the likelihood that the opportunistic Abyssinians might send an army to support him. It was all a dream; they just wanted time to re-occupy some border territory. Abdullahi was also vexed by harsh words between his brother Yaqub and eldest son, Shaykh al-Din. Then, on 27 January, the drumming stopped; Abdullahi had decided not to march an army down the Nile but to await the Anglo-Egyptians at Omdurman.

The Emir Mahmud wad Ahmed the Khalifas principal commander in the north (and also his nephew) had repressed a revolt at Metemma in 1897 massacring over 2000 of its inhabitants. Missing an opportunity to fortify Berber and hold onto it ahead of the Sirdars troops, trying to keep together a discontented army, he awaited instructions from the Khalifa. The word finally came advising a withdrawal to Omdurman. Mahmud refused; he felt it would have a harmful effect on morale and lead to further desertions. For weeks he had been begging for reinforcements; these now arrived under Osman Digna who brought 4000 ansar. But the extra numbers only added to Mahmuds problems and it left the warriors with a divided command.

The 14,000-strong Anglo-Egyptian Army was now on the Atbara and so in early February the dervishes started to move out to meet them. Soon the two emirs were quarrelling; Mahmud wanted to stick close to the Nile, but Osman Digna pointed out that this left the ansar at the mercy of Kitcheners gunboats. Reaching Nakheila on the Atbara, the Emir Mahmud decided to build a defensive thorn zariba amid a grove of dom trees. Osman Digna was aghast; he pointed out that the position on low ground was vulnerable and any camp near the main Nile and Atbara rivers made it easy for the Sirdar to launch a dawn attack after a nights march. He advised that they draw the enemy further into the desert, away from his river support, realising that the Sirdar would have no option but to follow and force a battle, unless he was willing to leave his flank and lines of communication open to dervish attacks. The Khalifa approved Osmans plan but Mahmud refused to listen. He wanted a fight.