LIFE

AMONG THE

SCORPIONS

Published by

Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2017

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110002

Copyright Jaya Jaitly, 2017

All photographs in the book are courtesy the author, unless otherwise mentioned.

Photograph on the back cover: Jaya Jaitly, George Fernandes and Nitish Kumar at a peace march in Patna, Bihar, 2000. Courtesy: AFP/Getty Images.

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the authors own and the facts are as reported by her which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-81-291-4909-1

First impression 2017

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 2 3 1

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publishers prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

For my children Akshay and Aditi, although they say they do not require a formal dedication from me.

To my craftspeople, my larger family, who have unknowingly given me solace when I needed it the most, but are not likely to read this book.

~

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

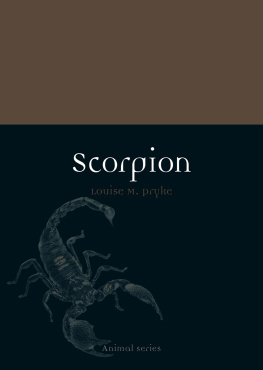

Once, not too long ago in 2001, a twenty-four-year-old woman in Kota Baru, Malaysia, emerged from a two-by-six metre glass cage after living with 2,700 poisonous scorpions for thirty days. According to news reports that went around the world, she left the enclosure, which was positioned in the local museum, for just fifteen minutes every day to use the bathroom. She survived seven stings, two of them serious. Although she received a certificate from the museums chairman, acknowledging her as the scorpion queen, she said that one of her best rewards was making some new clawed friends. I am particularly fond of two scorpions, and I named one of them Bob, she said.

It would be difficult for me to understand why she performed the stunt.

When I read this story, I felt I was like the woman in that glass cage, her every move being watched by everyone outside. There was nothing one could hide. There was nowhere to escape. It was a public act for some intangible reason that was hard to define. Like her, I too made a couple of good friends. One of them could be called George Fernandes. He was not really one of the scorpions but, being among them, he taught me to survive them.

My storytelling does not lead to the conclusion that politics for a woman is a hellish choice and should be avoided. Quite to the contrary, it is cathartic, and teaches more about life in all its ramifications than anything else can. As in every other path one chooses to take in life, it is how we deal with what comes our way that forges the steel in us. It is best not to expect success or happiness in public life. At different times, survival itself is success enough, and happiness can be just the experience itselfat times tragic, and others, sublime.

My story is therefore not about me, but just an example of what a woman in India amid politics and public life, and its many-facedness, experiences in trying to keep her integrity and humanity intact.

A life is never a linear journey with a clear beginning and a perceptible end, unless you count the moments of birth and death. There is never total recall. When remembering what matters, one counts those incidents that left an impression on ones mind for some inexplicable reason. We also recall an experience as meaningful only if it carries a thread into a later context. This happens when some situations repeat themselves in different forms, and, within it, ironies reinforce earlier incidents. Our mind absorbs and records everything but we often remember only parts as worthy of our attention. This interplay and replay of incidents and experiences cannot be kept smoothly chronological if one really wants to draw meaning out of them. Consequently, my book follows the same pattern-less pattern, going back and forth in time, and sometimes proceeding along a straight line.

Memoirs are usually written when a feeling of retirement sets in. However, when there is no pause in the many aspects of ones work that covers decades, and when some battles are yet to be fought and won, a memoir becomes just another layer of activism in the palimpsest of life.

MY BEGINNINGS

Amidst Matriarchy and Bureaucracy

I T WAS A TIME OF transitions. Great Britain was preoccupied with the war against Hitler. Indians were in the throes of the last years of colonial rule. Mahatma Gandhis voice had captured the hearts and minds of millions. And yet, the British in India continued moving the entire trappings of the governing bureaucracy from the colonial seat of Delhi up the hills to Simla to enjoy its cooler weather for six months of the year. My father, oddly named Krishna Krishna Chetturone Krishna after his father and one for himselfwas a part of that bureaucracy. Thats how we came to be in Simla in the summer months of 1942, and I, a girl of South Indian parents, came to be born in the northern part of India. I was born ten years late and a month too early when my mother, Meenakshi Chettur, went into labour following a fall down a slope. One wonders why she would have chosen to wear fashionable high heels to go for a walk along a hilly path while heavily pregnant. But there it was. The result: a fall, and the birth of a premature daughter.

~

Our family belonged to the famous matrilineal society of Kerala which rejoiced when a girl was born. No frowns and tears or worrisome thoughts about dowries. No oppressive patriarchy silencing the womans voice. Social scientists unequivocally state about the Nairs of Kerala that in even as late as into the nineteenth century, the absence of daughters meant a crisis. The New York Times of 29 January 1988 described Kerala as a place Where the Births Are Kept Down and Women Arent.

At that time, the position of women in the Nair community was far ahead of that in other parts of the country. Even while the entire social structure was segmented into various groups and castes, Nair women were accorded access to personal choices, the right to property, respect, and a freedom that extended to even selecting ones sexual partners. While the Brahmin Namboodris were the undisputed elite, the Nairs, who were initially Sudras, called themselves Kshatriyas; the Nairs were allowed a high caste status by the Namboodris who kept them as their warriors and retainers. Contrarily, the untouchable lower castes were expected to cross over to the other side of the road if a Brahmin was walking along it. Even during the innocence of early childhood, I was aware of the derogatory tone in which some of the family elders referred to these castes. It was their way of feeling Brahmin, at the top of the caste ladder, when, in reality, they were not.

~

Marumakkatayam , as matriliny is known in Malayalam, is believed to have begun in the eleventh century during, and as a result, of the hundred-year war between the Chola and Chera kingdoms. Since men were needed in the battlefield, the management of the household and family properties was exercised through the continuing presence of women in the house of their nativity. Inheritance passed through the womens line, and their children remained the wards of their mothers, since their fathers often established new alliances with other Nair women available nearer the battlefields. The maternal uncles of these children became the heads of the household. The elderly males usually made decisions regarding war, trade or religious ceremonies, but women and men had equal freedom to acquire and discard as many partners as they wished during their lifetime. My mother once let slip that my great-grandmother, her fathers mother, who ruled the household like a true matriarchal tyrant, actually went through five husbands. The last was the cook with whom she chose to hold hands while taking a holy dip in the Ganga. Pati, as everyone called her, of course, made sure that all the men in her life were Brahmins, including the last one. However, since I was the grandchild of her son and not her daughter, I was not a Brahmin, and hence no meals at the high table.