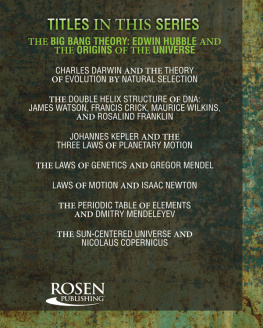

Series 117

This is a Ladybird Expert book, one of a series of titles for an adult readership. Written by some of the leading lights and outstanding communicators in their fields and published by one of the most trusted and well-loved names in books, the Ladybird Expert series provides clear, accessible and authoritative introductions, informed by expert opinion, to key subjects drawn from science, history and culture.

The Publisher would like to thank the following for the illustrative references for this book: : courtesy of CERN.

Every effort has been made to ensure images are correctly attributed; however, if any omission or error has been made please notify the Publisher for correction in future editions.

MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Text copyright Marcus Chown, 2018

All images copyright Ladybird Books Ltd, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover illustration by Chris Moore

ISBN: 978-0-718-18785-9

Marcus Chown

BIG BANG

with illustrations by

Chris Moore

Further Reading

Stephen Hawking A Brief History of Time (Bantam, 1989)

Steven Weinberg The First Three Minutes (Basic Books, 1993)

Alan Guth The Inflationary Universe (Vintage, 1998)

Brian Greene The Elegant Universe (Vintage, 2000)

Marcus Chown The Magic Furnace (Vintage, 2000)

Simon Singh Big Bang (HarperPerennial, 2005)

Alex Vilenkin Many Worlds in One (Hill & Wang, 2007)

Marcus Chown Afterglow of Creation (Faber and Faber, 2010)

The day without a yesterday

The greatest discovery in the history of science is that there was a day without a yesterday. The universe has not existed for ever. It was born. Around 13.82 billion years ago all matter, energy, space and even time erupted into being in a titanic fireball called the Big Bang. The fireball began expanding and, out of the cooling debris, there eventually congealed the galaxies great islands of stars of which our Milky Way is one among an estimated 2 trillion others. This, in a nutshell, is the Big Bang theory.

Whatever way you look at it, the idea of the universe popping into existence out of absolutely nothing is utterly bonkers. For the average person it immediately prompts questions such as: What was the Big Bang? What drove the Big Bang? And what happened before the Big Bang? The last is the most awkward question of all. It was largely because of the need to answer it that most scientists had to be dragged kicking and screaming to the idea of the Big Bang. What forced them to accept it was one thing, and one thing only: evidence. And the evidence, it turns out, is literally all around us

The heat of the Big Bang

The Big Bang fireball was like the fireball of a nuclear explosion. The heat of such an explosion, however, eventually dissipates into the surroundings. But the universe has no surroundings. By definition, the universe is all there is. So the heat of the Big Bang fireball had nowhere else to go. It was bottled up in the universe. Consequently, the heat afterglow of the Big Bang is still around today. Greatly cooled by the expansion of the universe, it appears not as visible light but principally as a type of invisible light known as microwaves. TV aerials pick up microwaves. If you were to tune an old analogue TV between the stations, 1 per cent of the static on the screen would be from the Big Bang.

The afterglow of the Big Bang fireball accounts for 99.9 per cent of all the particles of light, or photons, in the universe, with the light from the stars and galaxies accounting for only 0.1 per cent. If you had eyes that could see microwaves, the whole universe would appear to be glowing brilliant white. It would be like being inside a giant light bulb. But, although the afterglow of the Big Bang is the single most striking feature of the universe, it took a long time to realize we live in a Big Bang universe.

The Big Bang Einsteins blind spot

Before 1915 all ideas about the origin of the universe had no more factual basis than fairy stories. After 1915 it was possible to come up with a scientific explanation. What changed everything, in November of that year, was the announcement by Albert Einstein of his theory of gravity the general theory of relativity.

Einsteins genius was to realize that, although we are unaware of it, a mass like Earth creates a valley in the space-time around it. Other masses like you and me try to fall to the bottom of the valley, but the Earths surface gets in the way. To explain our tendency to fall we have invented a force called gravity that pulls us down. But there is no such force. We are simply responding to warped space-time.

In 1916 Einstein applied his theory to the biggest mass he could imagine the universe and created cosmology, the science of the origin, evolution and fate of the universe. Because he was wedded to Isaac Newtons idea that the universe had no beginning and looks the same for ever, he proposed that empty space exerts a mysterious repulsive force that nullifies the attractive force between masses and keeps the universe static. Thus he missed the message in his own theory.

But others did not.

The restless universe

To simplify his complex theory so that he could deduce something about the universe, Einstein assumed it had looked the same at all places and at all times. In 1917, however, the Dutchman Willem de Sitter dropped this assumption, proposing that the density of the universe changed with time. From this he concluded that space must be either shrinking or expanding. The only trouble was the universe he imagined contained no matter and so was not realistic.

In 1922 the Russian Aleksandr Friedmann found that the universe would still be shrinking or expanding even if it contained matter (which, of course, it does). And this discovery was made independently in 1927 by the Belgian Catholic priest Georges Abb Lematre. Today FriedmannLematre universes are more commonly known as Big Bang universes.

Einstein was wrong. The universe is not static and unchanging. We live in a restless universe. In an expanding Big Bang universe every mass flees from every other mass. And the further apart two masses are, the faster they flee, with masses that are twice as far apart as others receding at twice the speed, three times as far apart, three times the speed, and so on.

Next page