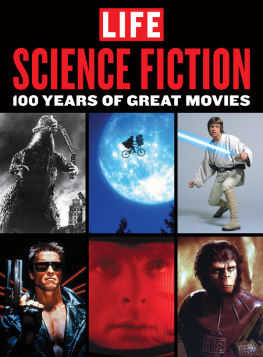

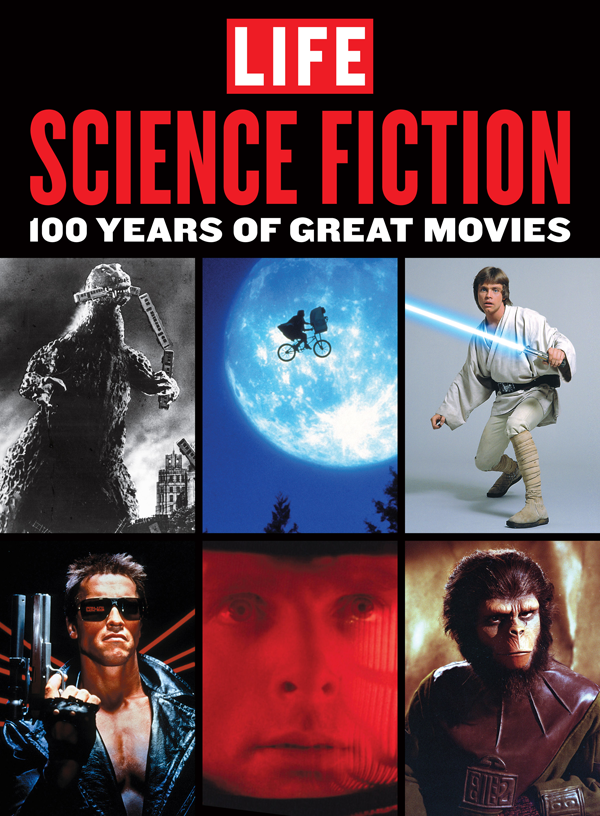

SCIENCE FICTION

100 YEARS OF GREAT MOVIES

EVERETT

The Star Child from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

INTRODUCTION THE HISTORY OF SCI FI CINEMA

APIC/GETTY

A LONG TIME AGO, in cinemas far, far away, the Man in the Moon showed up in French filmmaker Georges Mliss 1902 film, Le Voyage dans la Lune, the first science fiction movie. After World War I, Mlis was reduced to operating a toy shop in a Paris train station.

He was a magician, a toy-shop owner, and a shoe manufacturer, but first and foremost Georges Mlis was a filmmakerbest remembered today for his pioneering use of cinema to transform reality instead of just to document it. His most famous work, 1902s nearly 13-minute Le Voyage dans la Lune, was the first science fiction film and the first to show a voyage into space. He invented everything, basically, said director Martin Scorsese, whose 2011 film, Hugo, pays tribute to Mlis. He invented it all.

Le Voyage dans la Lune was loosely based on Jules Vernes From the Earth to the Moon and H.G. Wellss The First Men in the Moon. Though the two writers methodologies were wildly differentVerne tried to ground his novels in science, while Wells cheerfully threw facts to the windthe novelists invented many of the tropes that underlie the genre to this day: time machines, space travel, and lost worlds, for starters.

In 1910, Thomas Edisons 13-minute Frankenstein, based on Mary Shelleys 1818 novel, became one of the first American science fiction films. A few years later, feature-length SF films began being producedoften fueled by gimmicks. (Dubbed The First Submarine Photoplay Ever Filmed, the 1916 adaptation of Vernes 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea featured some of the first underwater photography.)

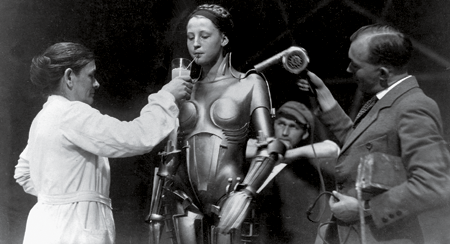

In 1927, SF cinema took a stratospheric leap forward with the German expressionist Fritz Langs silent film Metropolis, then the most expensive movie ever made (over $1.2 million) and an enduring influence on the genre. (Not to mention on music videos by Madonna and Queen.) And when King Kong was released in 1933, a mob of boys went quietly mad across the world, then fled into the light to become adventurers, explorers, zoo-keepers, filmmakers, the pioneering SF writer Ray Bradbury later said.

But in the first decade of talkies, cinematic SF was often synonymous with, of all things, musicals. In 1935s The Phantom Empire, singing cowboy Gene Autry discovers the technologically advanced civilization of Mu, 20,000 feet underground, now threatened by unscrupulous speculators from the surface. (More than 70 years later, Avatar would feature a similar plot, albeit without Autry singing That Silver-Haired Daddy of Mine.)

With this kind of cinematic fare prevailing, its no surprise that pulp fiction became the eras most significant influence on the SF genre. Named after the cheap paper they were printed on, pulp publications reflected a variety of genresfrom mystery to Westerns to horror. Those devoted to science fiction featured the work of Bradbury, Robert Heinlein, and future Scientology guru L. Ron Hubbard. In the 1930s and 1940s, movie serials (exemplified by the big-budget Flash Gordon productions) joined pulps and comics as seminal inspirations for such dreamers as Steven Spielberg, Stephen King, and George Lucas.

In the latters case, at least, an interest in experimental film fused with pop culture influences. The so-called Father of Star Wars was as obsessed with the nonlinear narratives of, say, Jean-Luc Godard as he was with lurid comics. In fact, his first student film, Look at LIFE, was nothing but a collage of images fromyou guessed it LIFE magazine. Now its LIFE s turn to look at Lucas, along with (of course) his forebears, contemporaries, and cinematic children in this celebration of the best 20 SF films ever made.

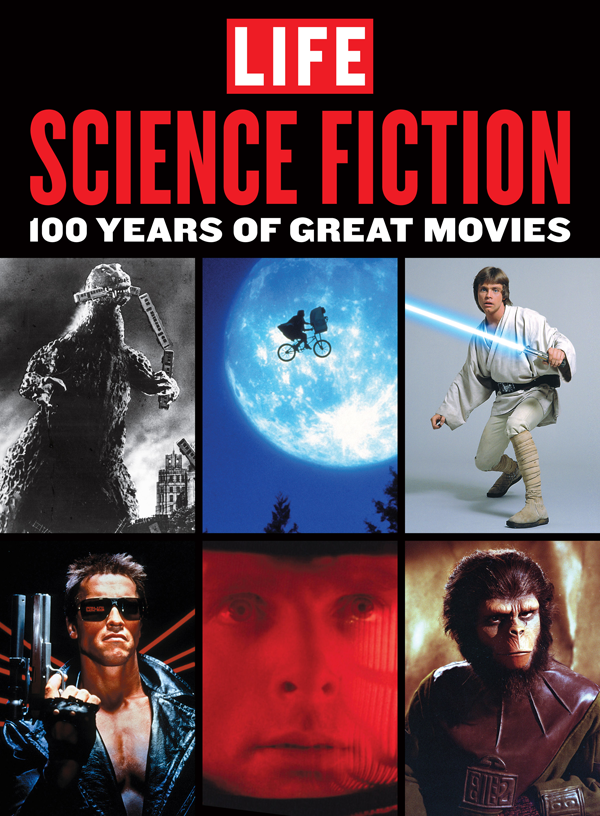

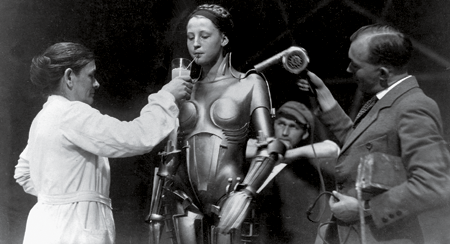

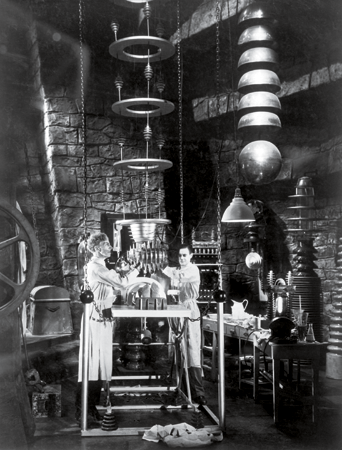

UFA/HORST VON HARBOU/KOBAL/ART RESOURCE, NY

BEHIND THE SCENES of director Fritz Langs pioneering 1927 German silent film, Metropolis

ERNEST BACHRACH/ RKO RADIO PICTURES INC., COURTESY PHOTOFEST

Zoe Porter, secretary to director Merian C. Cooper, helps to test a mechanical Kong hand for 1933s King Kong. Both films introduced special effects that transformed the industry.

ADVERTISING ARCHIVE/EVERETT

Metropolis s art deco poster. Thomas Edison made the first U.S. Frankenstein film in 1910

BETTMANN/GETTY

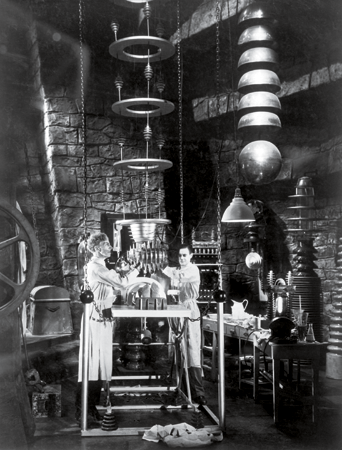

In 1935, the monster found love in The Bride of Frankenstein .

50s-60s AGE OF ANXIETY

JERRY TAVIN/EVERETT

HAS A MAN in a rubber monster suit ever been so menacing? Godzilla lays waste to postwar Tokyo.

In 1957, a 10-year-old boy sat watching Earth vs. the Flying Saucers in a Stratford, Connecticut, movie theater when the film abruptly stopped, the lights went on, and the rattled manager stepped onstage. I want to tell you, he announced to the audience of kids, that the Russians have put a space satellite into orbit around the earth. They call it... Spootnik.

This piece of intelligence was greeted by absolute, tomblike silence, the boyStephen Kingwrote nearly 20 years later. I remember this very clearly: Cutting through that awful dead silence came one shrill voice... that was near tears but that was also full of a frightening anger: Oh, go show the movie, you liar!

The idea that the hated Soviets had beaten the heroic United States into space was literally unbelievable for kids growing up in the Eisenhower eras strange circus atmosphere of paranoia, patriotism, and national hubris, King continued. Against this backdropa superficial sense of security and prosperity undermined by fears of Communist infiltration and nuclear warscience fiction increasingly added the resonance of metaphor to its pulp roots, examining social issues and the human (not to mention inhuman) condition in both complex and entertaining ways.

In the early 1950s, films such as Destination Moon and The Day the Earth Stood Still appealed to audiences and critics. A corresponding renaissance in print was driven by such writers as Arthur C. Clarke, Philip K. Dick, and Isaac Asimov, who brought a more personal, idiosyncratic approach to the genre than their predecessors had. In the process, SF became increasingly a part of the mainstream. The rise of post-pulp magazines that were open to edgy material led to the publication of such classics as Walter Millers A Canticle for Leibowitz and Daniel Keyes Flowers for Algernon, which later became the Academy Awardwinning 1968 film Charly.

Next page