Copyright 2018 by Dennis Oliver

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

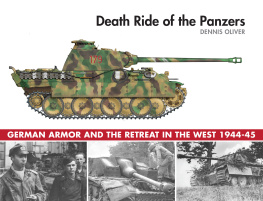

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Cover photos and illustration courtesy of Dennis Oliver

ISBN: 978-1-5107-2095-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-2096-1

Printed in China

Contents

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the staff at the National Archives and Records Administration in Maryland and Darren Neely, who helped source most of the photographs reproduced in this book. I would also like to thank Professor Yuri Shepelev of the University of St Petersburg, who was able to access a number of German wartime records held at the Russian Central State Archive, Karl Berne and Valeri Polokov for their advice and assistance, particularly in matters of formation and uniform insignia, Gary Kwan who was able to identify some of the units depicted in photographs from private collections, and Claudio Fernandez who assisted with the original research for the illustrations. Richard Hedricks research, translation, and interpretation of Kriegsstrkenachweissungen was invaluable. I would also like to acknowledge the research carried out by Martin Block, Ron Owen Hayes, and the late Ron Klages.

Introduction

B y early 1944, few in Germany and occupied Europe could have doubted that an Allied landing would be long in coming. Indeed, the design and building of static defense installations, which Hitler had christened the Atlantic Wall, had begun as early as March 1942. They were intended to stretch from the Franco-Spanish border along the Bay of Biscay to Brest, follow the Channel coast and the North Sea to Skagen in Denmark, and begin again at the Norwegian-Swedish frontier near the Oslofjord and continue as far north as the Soviet border. The defenses of the Atlantic Wall would also include the Channel Islands, particularly Alderney, which is closest to Britain. The Wall was to be made up of gun emplacements and bunkers constructed from concrete and steel, barbed wire fences, minefields, concrete walls, and fortified artillery positions. The strongest position was situated on the island of Sotra in Norway, where a complete turret taken from the battleship Gneisenau, with three massive 283mm guns, commanded the approaches to Bergen.

The required administrative effort alone was staggering, with some 600 different designs for bunkers, artillery, and machine-gun emplacements involved. As building progressed and resources became more scarce, weapons captured from the Czech, French, and Russian armies were pressed into service. Their use required additional amendments or alterations to the existing emplacements. The building program was given added impetus by the large-scale raids at St Nazaire, which took place just days after Hitler issued the initial order for the building of the Atlantic Wall, and at Dieppe, where over six thousand Allied troops were landed on four separate beaches. Nevertheless, and despite the claims of German propaganda, the construction of the Atlantic Wall was half-hearted. Far from being viewed as a potential invasion front, France was seen as a soft posting by most German troops.

As the result of an extensive inspection tour instigated by Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt (at the time Oberbefehlshaber West), which lasted from May to October 1943, the shortcomings of the German defenses became all too obvious. A key weakness lay in the extensive length of the Wall, which effectively prohibited any defense in depth; many German commanders felt that the system would at best delay an enemy landing. Importantly, the superbly trained and equipped German infantry unitsthe same who had thrown back the British and Canadian raiders at St. Nazaire and Dieppehad been continually called upon to supply replacements for the Russian front. By June 1944, the Atlantic wall defenses were manned by depleted formations, with one in six infantry battalions made up of Eastern volunteers from Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Ukraine.

Opinion was divided as to whether the coming invasion should be met on the beaches with all available resources, including tanks, or held by the defenses of the Atlantic Wall until the enemys intentions were clear and then countered by powerful armored reserves held much further inland. An advocate of the former was Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, who conducted a further investigation of the western defenses in November 1943 at the behest of Hitler. Tasked with upgrading the Atlantic Wall, Rommel was to assume command of Heeresgruppe B, the army group responsible for the Pas de Calais and Normandy, the most likely invasion areas. However, Rundstedt and the commander of Panzergruppe West, General Leo Freiherr Geyr von Schweppenburg, were understandably reluctant to bring their tanks within range of the enemys naval gunfire. In what may have been a compromise solution, and perhaps making a virtue of necessity, it was proposed that the German defenses should consist of what came to be called Crust, Cushion, and Hammer zones.

The Crust zone was the concrete and steel of the Atlantic Wall. The Crust would delay the Allied invasion forces, inflicting as many casualties as possible, until the armored reserves could be committed. It seems that by this time, only the most optimistic German planners believed that the Atlantic Wall alone would actually stop the invaders. Under Rommels direction, the Crust was reinforced with millions of mines and obstacles intended to stop or disable Allied landing craft. The Cushion zone was the area immediately inland from the beaches and it was planned that this would be defended by fortified emplacements providing a real defense in depth. However, as most of the available concrete had been used to create the Crust zone, the Cushion consisted of a system of trenches and bunkers constructed from wood and earth. The Hammer would be Schweppenburgs Panzergruppe West, controlling the bulk of the German armor, based much further inland.

When the invasion came, the assumptions of both sides would be sorely abused in the fighting that followed. Although the Normandy battles were for the most part brutal slogging matches conducted between groups of infantrymen, it would be the Panzer units which would time and again cut off an Allied penetration, hold up an enemy attack and finally, between the villages of Chambois and Trun in the Dives valley, save the bulk of the German Army in the West.

Despite the German preparations, the Allied landings on the beaches of Normandy in the early hours of June 6, 1944, and the subsequent establishment of a secure bridgehead could only be described as a spectacular, if qualified, success. The overly complicated chain of command imposed by Hitler, the lack of intelligence in matters as basic as weather forecasting, and the assumption that resisting the invasion would be no different in concept than the opposition of a river crossing (albeit on a larger scale) meant that the defenders were operating under a severe disadvantage. The German defenders were caught largely off guard. Those in the forward positions, the Crust, were swamped by naval gunfire or overrun by specialist bunker-busting tanks; although many held on to their positions for far longer than could have been reasonably expected, most were simply crushed by the weight of fire. Many of the battalions made up from Eastern volunteers fled or surrendered at the first opportunity.