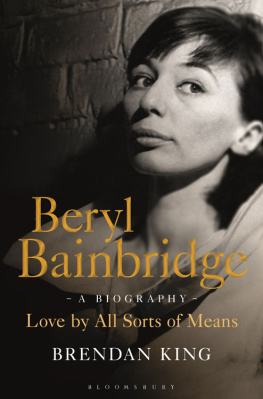

BERYL BAINBRIDGE

I go on making messy relationships, fail, and fling myself into a fresh one. I seem to have an intense craving for narcissistic gratification. I have to get love by all sorts of means...

Beryl Bainbridge, letter to Judith Shackleton, October 1963

BERYL

BAINBRIDGE

Love by All Sorts of Means

A Biography

BRENDAN KING

Beryl was a notoriously erratic speller and her unique and idiosyncratic orthography contributed to the way her correspondents perceived and interacted with her. In quoting from her diaries, journals and letters I have therefore left her original spelling for the most part unchanged, correcting only instances where the sense was difficult to follow. Minor slips in punctuation, such as forgetting to close quotation marks, have also been corrected.

I first started working for Beryl Bainbridge in 1987. Initially, I went round to her house in Camden Town once a week to help her deal with the increasing volume of letters and phone calls she had been receiving in the wake of two television series for the BBC, English Journey (1984) and Forever England (1986), and her weekly column for the Evening Standard. My job, insofar as it had a description, was to sort out anything that got in the way of her real work that of being a novelist. Over the course of the next twenty-three years, until her death in 2010, we established a working relationship that functioned surprisingly well given the difference in age and background. This was especially the case after 1992, as with the departure of her regular typist at Duckworth I took over the task of preparing the manuscripts of her novels, a process that included frequent telephone calls to query her over issues of style, grammar, form and structure and writers, like most creative artists, often find criticism of their work difficult to take.

Sometimes, when she was bogged down with writers block or struggling to come up with an idea for a novel, I would suggest that she write her autobiography, as it seemed to me that over the years she had told me many things about herself shed never made use of in her writing. But she always declined, saying that it was too difficult, that she couldnt remember things well enough, that she didnt have the energy. Instead, it became a kind of in-joke that I was her biographer in waiting. Then, over time, it turned into a settled notion.

After Beryls death the question of a biography inevitably arose. With her familys permission I began searching through the massive archive of material she had kept and stored in various filing cabinets and trunks in her work room at the top of the house the laboratory as she called it and the sizeable collection of manuscripts and other literary material she had sold to the British Library in 2005.

Many of the circumstances and events of Beryls life were already familiar to me: not only had she told me about them herself, she had written about them in pieces of journalism, spoken about them in interviews, and famously used them as the basis of her novels. But I soon began to notice a considerable difference between the story revealed by her private diaries, journals and correspondence, and the version of her life she had published, whether in fictional or non-fictional form. And the more I researched the more discrepancies I found, until it began to seem as if everything that had been published about her was either misleading or riddled with factual errors. Yet the source of much of this information had been Beryl herself. Surely, if anyone knew the facts of their own life, it would be the person who actually lived it?

There is, of course, a simple reason why the published accounts of Beryls life dont always match the private record. Whether in interviews or in the articles and books she was writing, she tended to rely on her memory for the details of the stories she was telling. Beryl was very proud of her memory. In an interview in 1973 she claimed to have whats called total recall,

But she did not have total recall and her memory was as prone to inaccuracy as anyone elses. Memory is a notoriously unreliable instrument the notion that it is a kind of permanent storage device, faithfully recording human experience, fixing it once and for all in the mind so that it can be recalled again and again in exactly the same form, is no longer one accepted by psychologists. Memories are more dynamic, more unstable, than we would like to believe; our recollections alter and adapt over time, they are shaped, consciously or unconsciously, by emotions, by new experiences, by changes in circumstance. Its not just that we forget certain things or emphasize others; we condense events in our mind, confuse one thing with another.

To give just a few examples. In Forever England, Beryl recalled that as a thirteen-year-old she went to see the great Polish pianist, Ignacy Paderewski, at the Floral Hall in Southport. After the performance she was taken backstage, dressed in her mothers best fox fur, to meet the musical legend. As Beryl described it: He was a small man with a lot of mad white hair and he said he thought I had some kind of specialness I remember the exact word but it was only because I was looking at

Despite the seemingly unforgettable nature of this experience, and the precise detail with which it is recalled, there is a problem: Paderewski died in 1941, when Beryl was nine years old, and there is no record of him performing in Southport. It is still possible she saw him play, though his last recital in Lancashire was at the Manchester Free Trade Hall in October 1938, when Beryl was almost six. Or it may be that she has simply mistaken some other distinguished white-haired pianist for Paderewski. Either way, the anecdote loses much of its value as an autobiographical memoir given its essential unreliability.

A second example shows that this kind of inconsistency is not an exception. Beryl mentioned as a key early experience in her theatrical career a week-long stint at a theatre in Bulwell, in which she and a schoolfriend performed a series of variety acts after having won a talent contest. Again a memorable event, one which Beryl herself said she had never forgotten. She duly records that prior to ending her turn with a recited monologue, the two girls performed the umbrella dance from Singin in the Rain. The problem here is that the film wasnt released until 1952, three years after she remembered dancing the routine for which it became so famous.

Our confidence in the reliability of such memories is shaken still further when we find that the talent contest in Bulwell was covered quite extensively in the local newspaper at the time, from which it becomes apparent that every verifiable detail Beryl recounts is wrong, including the name of the theatre and that of the other acts that performed alongside her. In fact the two girls did not win the talent contest, they were simply taking part in it, and they did not get to perform for a week, but only for two shows on the same evening, one at 6.15 and another at 8.00, as the rules of the contest required.

Perhaps the most striking, and in some ways the most troubling, example of this tendency of the memory to play tricks, is Beryls recollection of being taken, along with the whole of her school, to the Philharmonic Hall in Liverpool to see the unexpurgated version of the film taken by British troops entering Bergen-Belsen.novelist she would become. Yet no visit under the auspices of Merchant Taylors School was ever made to see the newsreel footage, which in any case would have been the standard edited footage presented by Path there were no unexpurgated versions floating around. Despite Beryls vivid memory that the entire school, from the ages of 7 to the 6th form were marched in file to see the film, there is no record of any such visit, and not a single pupil or alumni of the school remembers the event.

Next page