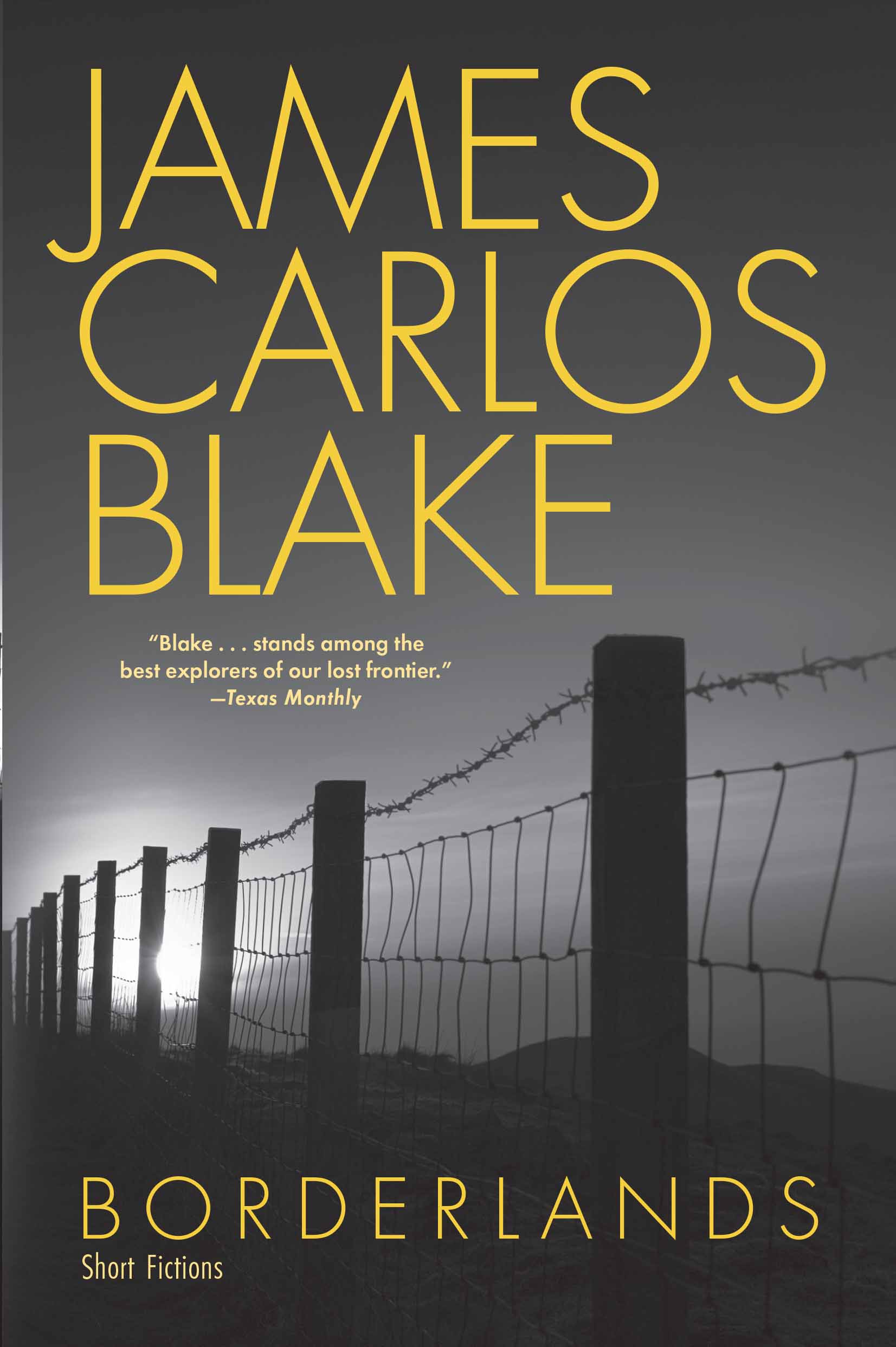

B ORDERLANDS

Also by James Carlos Blake

Novels

The House of Wolfe

The Rules of Wolfe

Country of the Bad Wolfes

The Killings of Stanley Ketchel

Handsome Harry

Under the Skin

A World of Thieves

Wildwood Boys

Red Grass River

In the Rogue Blood

The Friends of Pancho Villa

The Pistoleer

B ORDERLANDS

SHORT FICTIONS

JAMES CARLOS BLAKE

Grove Press

New York

Copyright 1999 by James Carlos Blake

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First paperback edition: Avon Books, 1999

First Grove Atlantic paperback edition: March 2017

ISBN 978-0-8021-2644-3

eISBN 978-0-8021-8943-1

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For

Nat Sobel

Where do we go when we die? He said.

I dont know, the man said. Where are we now?

Cormac McCarthy, C ities of the Plain

What need is this

We follow into ramshackle towns...

Listening for a whistle

To call us by name,

Waiting for a night train

To carry us out.

Marti Mihalyi, Transience

Never eat at a place called Moms, never play cards with a man named Doc, and never go to bed with anybody whos got more troubles than you do.

Nelson Algren

Character is fate.

Heraclitus

CONTENTS

THE OUTSIDERS:

AN INTRODUCTORY MEMOIR

THREE TALES OF

THE REVOLUTION

THE HOUSE OF

ESPERANZA

T H E O UTSIDERS :

An Introductory Memoir

I

I ve always been an outsider, a stranger in every tribe. Thats neither boast nor complaint nor plea for sympathy. And its certainly not a condition uncommon to others. Its the sense of remove from the world around him that defines the outsider, but this feeling of apartness goes beyond mere geography. Even in his own country, among his own fellows, in the midst of his own family, the outsider feels himself a stranger, a keeper of an alien heart.

Some feel like outsiders for obvious reasons, some for reasons more complex, some for reasons utterly and ever unknowable. In my own case, blood heritage and a borderland childhood no doubt played their parts.

I am the fourth generation of men in my family to be born in Mexico, all of us descendants of an American who himself was sired by an English pirate. But Im the sole member of those generations who was raised in the borderlandsthat long brute region flanking both sides of the Mexican-American frontier for roughly a couple of hundred miles in either direction and ranging for more than two thousand winding miles from the mouth of the Ro Grande at the Gulf of Mexico to its western terminus at the California shore of Alta California. All along this frontier the outlands of two countries come together to form a culturally sovereign province. It is almost entirely desert country, stark and shadeless and short on mercy, and, with few widely scattered exceptions, sparsely inhabited. From the scrublands of South Texas and Coahuila to the fierce basins and ranges of the Big Bend and Chihuahua to the desert dunes of Arizona and Sonora, its people are mostly of a nature less wholly Mexican or American than an amalgam of both, a nature as distinct and remote and isolate as the borderlands themselves.

II

T he pirate was my great-great-great-grandfather Robert Blake, the black sheep of a landed English family. He left Olde England for the New one and lived for a time in New Hampshire, where he was married and fathered a son before sailing south to plunder in the Gulf of Mexico. He was captured in 1826 and executed in Veracruz and was thus the first Blake buried in Mexican ground. His son John married a woman of established New England family whose fortune derived from paper mills, and he gained appointment as U.S. consul to the Mexican state of Jalisco. Thus, like his father before him, did John Blake venture to Mexico, albeit to a better fate. He fell in love with the country and established a profitable mill he named the Hacienda Americana, which remained in the family until the Revolution of 1910. He sired three sons but only one, Carlos Enrique, lived to maturity. Carlos was already managing the mill when his father was stabbed to death on the church steps one Sunday morning by a foreman with a grievance. A photograph of great-grandfather Carlos shows a quintessential patrn whose stern mustached visage and hard eyes bespeak no tolerance whatsoever for fools or disrespect. He is flanked by his familyby his four daughters, his two sons, and his Creole wife, Adela Arrias, born in Mexico of pure Spanish bloodline and the first Mexican woman taken to wed by a Blake. One son, Toms Martn, would be killed at age eighteen when his mount fell on him. The other, Juan Sotero, was my grandfather. He rose to the rank of colonel in the Mexican army engineering corps, married a Creole poet named Esther Hernndez, and begat two sonsJuan Jaime and Carlos Sebastin. Carlos would become my father.

III

M y father was, like his father, a civil engineer, more particularly a builder of roads. He loved the profession not only for itself but as much for the way of life it allowed, and he reveled in that life for ten years before he got married. It was fitting that he built roads, for he loved to travel on them, loved to drive his Model A Fords, his Buicks, his Packardsall the cars he came to own in those wild free yearsloved to drive them hard and fast over roads however rugged and raise great plumes of dust behind him.

As a young man, he went to work for his father in the borderlands and over the next few years built roads to Piedras Negras, just across the Ro Grande from Eagle Pass, Texas; to Villa Acua, across the river from Del Rio; to Ojinaga, across from Presidio. He built roads in various portions of the Sonoran desert including the brutal Desierto de Altar, comprising the whole of the region between the southwest corner of Arizona and the Sea of Cortez. He had by then formed his own company, and he and his crews played as hard as they worked. Whenever there was a town within thirty miles of their camp, they would head for that towns cantinas at the setting of the sun and there drink and gamble and frisk with the girls and fight with other construction crews and generally have a fine time. He loved the desert townsAgua Prieta, Nogales, Sonoita, Mexicali. Loved Baja California above all places on earth, loved Tecate and Tijuana and Ensenada. Sometimes they went to towns on the American side of the borderCalexico, Tucson, El Paso, Las Crucesjust for the novelty of it, to flirt with the blondes. At a time when few Mexicans traveled more than fifty miles from home in their lives, my father and his crews were men of vastly traveled experience, worldly men of the borderland, and not one of them yet thirty years old.