PENGUIN BOOKS

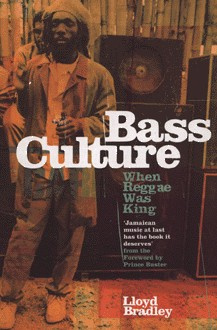

BASS CULTURE

Lloyd Bradley was born in London in 1955. As a teenager he was sucked into the nether world of north London sound systems, and he owned and operated the Dark Star system during the late seventies. For the last twenty years he has written about music for many magazines and newspapers, including NME, Black Music Magazine, the Guardian, Q and MOJO. He is also a classically trained chef and lives in north London with his wife and two children.

Bass Culture

When Reggae Was King

Lloyd

Bradley

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published by Viking 2000

Published in Penguin Books 2001

Copyright Lloyd Bradley, 2000

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-192817-3

For Diana, George and Elissa

The people that reggae was being made for never separate it into this style and that style. No. This is music that's come down from slavery, through colonialism, so it's more than just a style. If you're coming from the potato walk or the banana walk or the hillside, people sing. To get rid of their frustrations and lift the spirits, people sing. It was also your form of entertainment at the weekend, whether in church or at a nine night or just outside a your house, you was going to sing. If you're cutting down a bush you're gonna sing, if you're digging some ground you're gonna sing. The music is vibrant. It's a way of life, the whole thing is not just a music being made, it's a people a culture it's an attitude, it's a way of life coming out of a people. / Rupie Edwards

Contents

Acknowledgements

Writing Bass Culture: When Reggae Was King has been an adventure. It's taken me to Jamaica, New York, Miami, parts of London I'd forgotten existed and the most distant recesses of my record collection. For all this I am enormously grateful. But far more so than that, it's got me into and, quite thankfully in a couple of cases, out of situations that have hugely expanded my life-experience, given me a great feeling of privilege or quite simply made me laugh. I've helped Leroy Sibbles move house; I've felt Prince Buster's head; I've sat on a wall with Big Youth eating windfall custard apple; I've talked to Lee Perry for an hour and got secondarily red; I've quaffed fine wine with Dennis Bovell; broken bread at a dreadlocks camp; been stopped, with Bunny Lee, at 3 a.m. by an eradication squad; got roped in as navigator on the Wailers' tour bus; been abandoned on a particularly twitchy Trench Town street corner for forty minutes while the guy that was carrying me round went off and did God knows what; had the piss taken out of me royally by Bobby Digital and Luciano; interviewed Burning Spear when, for no reason I could see, he had no trousers on; taken tea in the very room in which Dennis Brown was born; taken my life in my hands with Junior Delgado's driving on thankfully empty Kingston streets; and, most of all, during the six years it's taken to put the book together I've been treated with massive courtesy, hospitality, helpfulness and respect by almost everybody I've come into contact with.

It's no accident that the handshake you pick up within hours of touching down in Jamaica involves the right clenched fists being alternately struck top against bottom, then the knuckles pressed together. It signifies strength and unity, and sums up how I felt whenever I had to spend time on the island. Therefore, the biggest shout has to go out to the entire population of Jamaica. It was their creativity, spirituality, warmth, wit and resilience in the face of appalling outside manipulation that gave me something to write about in the first place. I hope I've done them justice. But on a more immediate level, very rarely was I treated with anything other than hospitality by anybody I met on my many visits to Jamaica not just in the music business, but in the bars, in the cafs, in the streets, in the shops and in the hotels. London taxi drivers could do worse than take customer-relations advice from their Kingston counterparts.

Specifically on the island and its diaspora I have to thank those who gave up their time to invite a complete stranger into their homes or places of business and show him kindness beyond the call of duty as they told their tales. These were guys who had no product to push but were still willing to share knowledge, history, anecdotes and opinions on a range of subjects way beyond the music itself. Their reward, as several most flatteringly explained, was that somebody finally wanted to write that stuff down. In alphabetical order, a big five on the black-hand side goes to Dennis Alcapone, Monty Alexander, Horace Andy, Buju Banton, Dave Barker, Aston Family Man Barrett, Big Youth, Pauline Black, Dennis Bovell, Burning Spear, Fatis Burrell, Gussie Clarke, Jimmy Cliff, Junior Delgado, Bobby Digital, Brent Dowe, Sly Dunbar, Rupie Edwards, Derrick Harriott, Cecil Heron, Junior Cat, Bunny Lee, Byron Lee, Lepke, Little Ninja, Luciano, D J Pebbles, Lee Scratch Perry, Ernest Ranglin, Michael Rose, Leroy Sibbles, Danny Sims, Spragga Benz, Jah Vego and Drummie Zeb. The inspiration was all yours, the mistakes are all mine.

Special thanks, however, have to be given to Linton Kwesi Johnson for the loan of the title and to Prince Buster for the Foreword, also to both him and his wife Mola for all the kindnesses they've shown me in Miami and London.

In New York, the reggae archivist, tireless soldier for the cause and all-round excellent fellow Tom Tyrell couldn't have been more helpful. The same goes for Lisa Cortez, who shared some fantastic information; and irrepressible Murray Jah Fish Elias, whose Big Apple anecdotes are matched only by the sheer brilliance of the Big Blunts compilation albums he puts together.

At home in the UK are people who deserve as much credit for Bass Culture: When Reggae Was King as I do: Allister Harry read every word and passed a series of detailed comments as amusing as they were instructive; Rae Cheddie was the man who, thirty years ago, turned this dyed-in-the-wool soulboy on to reggae, and more recently answered even the most inane queries quicker than you might have thought possible; Eddi Fiegel, whose advice, conversation and friendship did so much to keep me focused; Keith Stone of London's premier reggae retailer Daddy Kool Records (020 7437 3535), who'd not only answer questions but let me listen to virtually any tune I didn't have from the last thirty-five years; Patricia Cumper of the Jamaica High Commission Information Service, who entered into the spirit of things with great gusto; and Margaret Duvall, Deborah Ballard and Gaylene Martin, whose casual reggae knowledge and perpetual helpfulness never ceased to astonish. And of course my family, Diana, George and Elissa, who shared their house, their lives and their holidays with a man who became somewhat possessed, and John Bradley (my dad), of whom I haven't seen nearly enough recently.

Next page