Copyright 2015, 2017 by Philip Kaplan and Andy Saunders

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Cover photographs courtesy of Philip Kaplan

Adapted from Little Friends

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-0512-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-0517-3

Printed in China

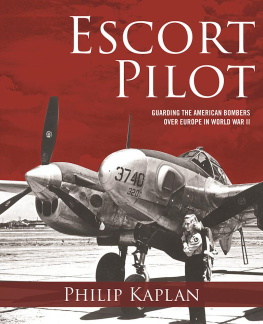

The cockpit of a newly restored P-51 Mustang escort fighter.

CONTENTS

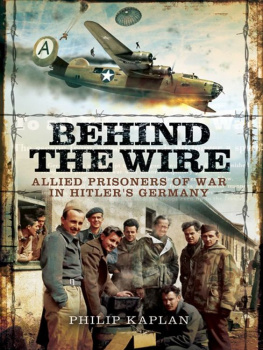

A briefing session of 4th Fighter Group pilots at Debden, Essex, in 1944.

During World War II he had total control of a 400 mph fighter and eight machine-gunswith no radar, no auto-pilot, and no electronics. At the touch of a button he could unleash thirteen pounds of shot in three seconds. He had a total of fourteen seconds ammunition. He needed to be less than 250 yards from the enemy to be effective. He and his foe could maneuver in three dimensions at varying speeds and with an infinite number of angles relative to each other. His job was to solve the sighting equation without becoming a target himself. His aircraft carried ninety gallons of fuel between his chest and the engine. He often flew over 35,000 feet with no cockpit heating or pressurization. He endured up to six times the force of gravity with no G suit. He had no crash helmet or protective clothing other than ineffective flying boots and gloves. He had about three seconds in which to identify his foe, and slightly longer to abandon the aircraft if hit. He had no ejector seat. He was also a navigator, radio operator, photographer, air-to-ground attacker, rocketeer, and dive-bomber. Often, as in my case, he was only nineteen years old. He was considered too young and irresponsible to vote, but not too young to die. His pay was the modern equivalent of just under sixty new pence per day in 1940. Should he have been stupid enough to be shot down and taken prisoner, a third of that sum was deducted at source by a grateful country and never returned. However, every hour of every day was an unforgettable and marvelous experience shared with some of the finest characters who ever lived.

Paddy Barthropp, a fighter pilot of the Royal Air Force in World War II

I want to see you shoot the way you shout.

Theodore Roosevelt

EVERYTHING ABOUT BRITAIN was strange to the newly arrived Yank. The countryside was greener than anything he had ever seen back home. The weather was lousy and so was the food. The houses looked ancient. The money made no sense to him. The people drove on the wrong side of the road. And when they spoke to him, he couldnt always understand what they said. As Oscar Wilde had put it: We really have everything in common with America these days except, of course, the language. And there were the shortages, the blackout, the bomb damage, the long lines of shoppers, the crowded trains, the sight of so many men and women in so many different uniforms and the haggard but unbeaten civilians.

The American fighter pilot, however, had made a relatively smooth transition to the UK assignment. First, there had been a trickle of U.S. volunteers into the RAF during the first year of the war in Europe, then a flood of aviators for the Eagle Squadrons preceded the great deluge of airmen arriving late in 1942 to serve with the Eighth and Ninth U.S. Army Air Forces in Britain. With the same mission, and sometimes the same airfields and equipment, the fighter pilots of the USAAF and the RAF were thrown togetherliving, flying, fighting, and dying alongside each other.

TO BLIGHTY

Lt. Col. James Clark briefs his 4FG pilots at their Debden base.

The heavily-armed Lockheed P-38 Lightning escort fighter.

The 31st Fighter Group was the first American fighter unit to be sent to Europe. Its official diarist commented that operationally we worked direct with the British, which in England was highly efficientabout as good as could ever be attained. It was, for the 31st, a close partnership strengthened by the use of British aircraft on British bases. The 307th Fighter Squadron at Biggin Hill, the 308th at Kenley, and the 309th at Westhampnett, all part of the 31st Fighter Group, flew the Spitfire operationally, and the Dieppe raid on August 19, 1942, was their first action. There, Second Lieutenant Samuel Junkin of the 309th shot down a Focke Wulf Fw 190 fighter and became the first USAAF pilot to claim a kill in the European air war. For the first time, pilots of the Eighth Air Force had flown in combat along with fighter pilots of the RAF. That day the American 308th was led into battle over the Dieppe beachhead by RAF Squadron Leader Pete Wickham who had been temporarily detached for the special assignment. Later, the Americans honored him with the Silver Star for outstanding aerial technique, operational skill, and great courage and determination. From July to October 1944, Wickham he was attached to another U.S. fighter group where he again served with distinction, at North Weald, northeast of London, the same base from which he had led No 111 Squadron, RAF. Another 111 Squadron pilot, George Heighington, had good reason to remember the American fliers with appreciation. On June 2, 1942, the North Weald wing was to be sent on a sweep of the Cap Gris Nez area, but recent losses had reduced the number of available aircraft. To make up for the shortfall, 111 Squadron borrowed a Spitfire from 350 Squadron and assigned it to Heighington.

It had been a last-minute arrangement and I only went to collect the aircraft as we were due to taxi out for takeoff, so had little or no time to set it up for my own use. During the flight out I set the seat for my own height, adjusted the rudder pedals, and set the throttle quadrant the way I wanted it. Then, as soon as we got over France, we were jumped by a whole hell of a lot of ME 109s and I switched on my gunsight ready to do battle. Nothing! It just didnt light up. Now this was not a good time to discover you had a malfunction in your gunsight, but I did my best. This turned out to be quite inadequate and I was immediately shot to pieces. As my logbook records: Cannon shells in wing and fuselage. Port cannon shot away. Starboard magazine exploded blowing away wing plates. Plates blown from port wing and tail unit. Engine misfiring. I was virtually dead in the air, just sitting at thirty thousand feet over Dunkirk and at the mercy of the next Luftwaffe pilot to spot me. Then, salvation. Another Spitfire arrived and escorted me back to England in a gentle dive, my engine eventually dying on me before I made a successful dead-stick landing at Manstonseverely shaken and lucky to be alive. The pilot who saved me never identified himself, but after I made a lot of inquiries he turned out to be a member of one of the Eagle Squadrons, Number 133. Id like to know exactly who he was so I could write him my much-belated thanks. That Yank saved my life.