To Sally:

Thank you for everything.

I could not have achieved as much without you.

Theres my truth,

theres your truth,

and then theres The Truth.

-Steve Smith

This is my truth -

some may disagree.

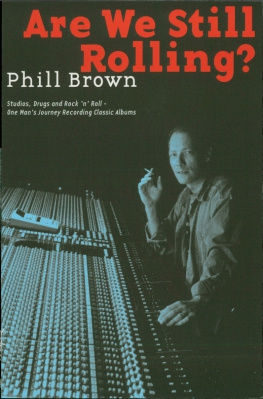

-Phill Brown

In memory of musicians, producers, family and friends who did not make it to 2010:

Robert Ash, Mark Bolan, John Bonham, Lenny Breau,

Linda Brown, Vicki Brown, Leslie Brown, Jenny Bruce, David Byron,

Sandy Denny, Dave Domlio, Jim Capaldi, Mongezi Feza,

Lowell George, Keith Harwood, Alex Harvey, Bill Hicks,

Nicky Hopkins, Brian Jones, Paul Kossoff, Vincent Crane,

Ronnie Lane, John Martyn, George Melly, Bob Marley,

Steve Marriott, Jimmy Miller, Denise Mills, Willie Mitchell,

Roy Morgan, Mickie Most, Harry Nilsson, Kenji Omura,

Robert Palmer, Mike Patto, Cozy Powell, Keith Relf, Lou Reizner,

Nigel Rouse, Del Shannon, Norman Smith, Alan Spenner,

Guy Stevens, Peter Veitch, Kevin Wilkinson, Suzanne Wightman and Chris Wood.

Copyright 2010 by Phill Brown

Published by Tape Op Books

www.tapeop.com

books@tapeop.com

(916) 444-5241

Distributed by Hal Leonard www.halleonard.com

Editing by Larry Crane

Proofreading by Caitlin Gutenberger

Art Direction by John Baccigaluppi

Graphic Design by Scott McChane

Scanning by Al Lawson

Legal Counsel by Alan Korn

Front Cover photo by Roger Hillier

Phill would like to thank Larry Crane and John Baccigaluppi at Tape Op Books, Roger Hillier, Julian Gill, Robert Palmer, Barbara Marsh, Dana Gillespie, John Fenton, Ray Doyle, Steve Smith, Sasha Mitchell, Caroline Hillier and Paula Beetlestone.

Tape Op Books would like to thank Leigh Marble, Caitlin Gutenberger, George Massenburg, Alan Korn, and Phill Brown, for trusting us.

9781476856094

Foreword

This is not a technical manual (although it will certainly function as one) - its a contemporary thriller. Phill Brown is a sound engineer. Its a mystery, even to people in the music business, as to exactly what a sound engineer does - are they part of the creative process or merely technicians? In the past 30 years, recording studios have moved from the engine room of a submarine to the bridge of a starship - baffling the outsider - although recording music will always be the same un-guessable adventure. Thats what Phil Brown has written here - an adventure story.

Look at the chapter headings. Laid out in the form of a diary, he takes us through the crazy journey that is making music. Not as an academic journal, but as a spiritual experience. With his laconic navigation, were steered through the centre of the ego hurricanes of creative madness. He is the Jiminy Cricket of recording sessions, and his excellent recollections of the excesses of morons and geniuses involved in creating melodies and rhythms for us to enjoy are sheer entertainment. Its a how-to book and a love story! A self-driven need to understand why creative people do what they do, and how to survive it and them.

Robert Palmer, 9 September 1997

Introduction

In the spring of 1995 I was in hospital having 12 inches of colon removed an experience I cant recommend despite the considerable skill of Mr. Chilvers, the surgeon at St Anthonys Hospital, Cheam, in Surrey. It seemed that my lifestyle had finally caught up with me. The two consultants and the other doctors I came into contact with were all in agreement about the cause of my predicament. As one of them said, Mr. Brown, this situation has been created by your long working days, poor diet, sedentary lifestyle and the combination of continuous adrenaline rushes and intense stress. The old saying  bust a gut comes to mind.

bust a gut comes to mind.

During my seven-day stay at St. Anthonys and previous two weeks of purgatory in a hospital in Tunbridge Wells, I had plenty of time to contemplate what I realised with surprise was nearly 30 years in the music industry. The doctors were right my present poor state of health was in many ways the legacy of this career. However, considering the abuse that my system had suffered and the high casualty rate among my many friends and acquaintances, I reflected that my situation could have been a lot worse. At least I was still alive, which was a good position from which to start my recovery. While lying in my hospital bed with a drip in my arm and a cocktail of, for once, completely legal drugs pouring through my body, I consoled myself by recalling the more enjoyable projects I had been involved with. I had worked with some of the greatest acts in the business, including Jimi Hendrix, Joe Cocker, Traffic, Spooky Tooth, Jeff Beck, Led Zeppelin, Robert Palmer, Bob Marley, Steve Winwood, Harry Nilsson, Atomic Rooster, Stomu Yamashta, John Martyn, Little Feat, Roxy Music and Talk Talk.

Now, in my hospital bed in 1995, I was unable to work at all for the first time in years, and my thoughts inevitably turned once again to past events. It seemed a good moment to look at my entire story so far.

When I began work at the bottom of the studio hierarchy as a tape operator, I discovered that there was an informal system of apprenticeship in the recording industry. I was expected to learn by watching and listening while I made tea and performed other mundane jobs about the studio. However, I never resented being the dogsbody. To work in a studio and to train under such engineers as Keith Grant, Glyn Johns and Eddie Kramer was a privilege, and I gained a unique approach and attitude towards recording that I carried with me through the next 30 years. Although in those early days everything seemed strange and new, I could have no notion of the crazy sessions that lay ahead, the extraordinary people I would work with or the wildly varied types of music I would help to create.

The sequence of events that led me to become a sound recording engineer began when I was still at school in the early 1960s. In 1964 my elder brother Terry started working at Olympic Studios in London as a trainee sound engineer. Since leaving school, he had been working at the post room of J. Walter Thompson, the advertising agency where our father had worked for 15 years. My brother was expected to rise through the ranks and become successful in the advertising industry. To me this seemed a dismal fate. However, one day Terry delivered a package to Olympic Studios. He caught a glimpse of an exotic world of unconventional characters, mysterious equipment and most attractive of all, exciting music. He decided to ask for a job at Olympic. My parents were not keen on this idea. They were conventional and careful in outlook, and were concerned that Terry would lose his pension and security.

At that time I was 13 years old and in my third year as a day pupil at Stanborough Park, a private day and boarding school in Garston, Watford. The school was run by the Seventh Day Adventists a nonconformist Christian sect with a firm moral code and strict principles. Children from all over the world were sent to Stanborough Park by parents who upheld these religious beliefs, but the school was also attended by local children. Most of these had failed their 11-plus examinations, an ordeal to which all children in state schools were subjected at the time. The successful minority was creamed off to a grammar school. The rest, which included me, would have to make do with secondary modern education. The only alternative was to opt out. This is what my parents decided I should do, due to the poor reputation of the three secondary modern schools within the area.

bust a gut comes to mind.

bust a gut comes to mind.