CONTENTS

Prologue

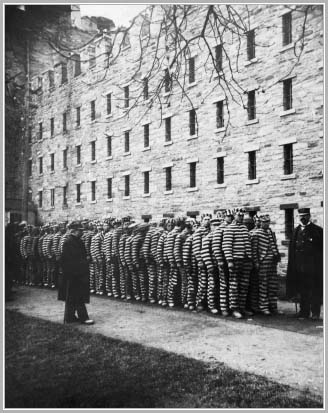

SING SING: FEBRUARY 1900

Part One

THE SOLDIER AND THE CLUBMAN

Part Two

BLANCHE

Part Three

DEGENERATE

Part Four

INQUEST

Part Five

THE PEOPLE VERSUS MOLINEUX

Part Six

THE MAN INSIDE

Part Seven

AFTERMATH

For Will and Mary Molineux

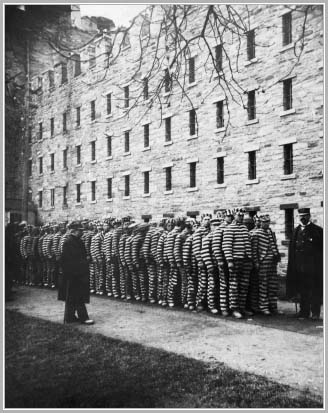

A t the start of the twentieth century, death by electricity was a relatively recent form of capital punishment. It was only in June 1888 that New York became the first state to pass a law replacing hanging with electrocution. Two years later, on August 6, 1890, a thirty-year-old ax murderer named William Kemmler became the first man to die in the chair. After being hooked up to the apparatus, Kemmler was hit with a high-voltage charge lasting seventeen seconds. When the shock failed to kill him, the switch was thrown again. This time, the current was kept on for more than a minute. As Kemmler roasted, the room filled with the stench of burning hair and flesh. Some witnesses vomited, while others fainted or fled in horror.1

Over the succeeding decade, more than three dozen criminals were put to death in New York by the new, presumably more humane, mode of execution. All were men. That particular gender barrier was broken in March 1899, when a hard-bitten housewife named Martha Place became the first female to be killed in the chair. In the weeks leading up to her electrocution, her case became a cause clbre. Even while reveling in the lurid details of her crime (Mrs. Place had smothered her seventeen-year-old stepdaughter after flinging sulfuric acid in the girls face), the New York JournalWilliam Randolph Hearsts wildly sensationalistic yellow papercrusaded for clemency on the grounds of her sex. The effort proved unavailing. Governor Theodore Roosevelt refused to commute her sentence, declaring that, when it came to punishment, female criminals deserved equality with men. On the morning of March 20, 1899, clutching a psalm book and muttering Lord, save me, Lord, save me, Mrs. Place was led to the death chair, becoming a pioneer of sorts in the womens rights movement.2

Eleven months later, during the second week of February 1900, the Sing Sing Death House received a convicted murderer whose notoriety outstripped even that of the infamous Mrs. Place. His name was Roland Burnham Molineux, andlargely thanks to the feverish attentions of Hearst and his fellow scandal-mongerer, Joseph Pulitzerhis case had riveted the country for more than a year.

At the time of his transfer to Sing Sing, he had already spent twelve months in the city prison, known as the Tombs. Since his arrest in early 1899, his clean-favored face had grown pasty and his athletes physique had lost much of its muscular tone. Still, at thirty-four years old, he cut a striking figure. Even behind bars he was never less than immaculately dressed, grooming himself each morning as though preparing to visit his club. Unfailingly suave (if not supercilious) in manner, he bore himself at all times like a gentleman of the highest rank. Throughout his trialthe longest at that time in the history of New York Statehe had barely been able to conceal his ennui. For a man convicted of what his accusers called the greatest crime of the age, he struck observers as a marvel of nonchalance.

Once immured in the Death Housean environment so grim that, by comparison, the Tombs seemed like a Newport hotelhe managed to maintain his unflappable air. At least in the beginning. Within weeks of his arrival, however, something happened that shook even Roland Molineuxs remarkable aplomb.

Among the other inmates on Death Row was a thirty-seven-year-old Italian immigrant named Antonio Ferraro. A year and a half earlier, in September 1898, Ferraro had bumped into a onetime friend, Lucciano Machio, on a Brooklyn street corner. Machio was overdue in repaying some cash he had borrowed from Ferraro, and before long, the two were hurling insults into each others face. The words grew uglier. Knives were drawn. Within minutes, Machio lay dying on the sidewalk, a gaping wound in his throat.3

Convicted and sentenced to die, Ferraro pinned his last hopes on an appeal. Late on the afternoon of February 23, 1900, however, he received word that the effort had failed and his execution would take place within the week. Ferraro did not take the news well. As one paper reported, he emitted a prolonged scream that broke in fearful violence on the silence of the Death House and terrified the other prisoners. For a half hour, the hopeless man shrieked hysterically and rushed around the cell, moaning and shouting curses.4

Though his priest, Father Orestes Allucci, eventually managed to calm him down a bit, Ferraro spent the next few days intermittently bursting into inhuman howls or spewing fearful blasphemies. Even on the morning of his executionMonday, February 26Ferraro was still violently protesting his fate. The curtains had been drawn in front of the other condemned cells, so that Roland could see only shadows. But he could hear Father Allucci say, Do you forgive your enemies?

Ferraro answered with a bitter curse.

But you must, Father Allucci pleaded as he walked beside the doomed man. Say yes, for Gods sake, say yes! You must, or God will not By then, the priest was weeping.

No! shrieked Ferraro. Nono!

That cry of maddened refusal was the last Roland heard of Ferraro. In another moment, the condemned man was led into the execution chamber. Later, Roland heard that it had taken five separate jolts of electricity to kill Ferraro. He had died, according to The New York Times, harder than any man who has so far died in the electric chair.5

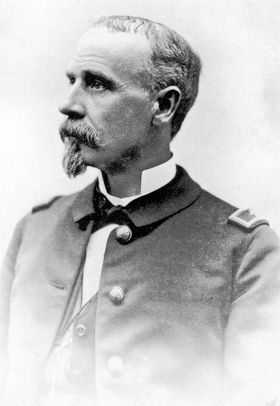

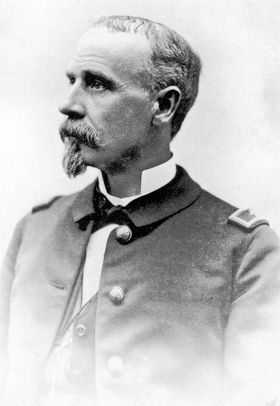

Roland was so badly rattled that, for days afterward, he found it hard to eat or sleep. Gradually, however, he recovered his composure. What, after all, did he have to fear? His father had vowed to win his freedom and bring him safely home. And if anyone could be counted on to keep his word, it was General Edward Leslie Molineux, who throughout his long and celebrated life had maintained a moral stance as upright as his posture; a man for whom the concepts of duty, honor, and justice were nothing less than sacredhowever quaint and outmoded they might seem to his son.

O n July 15, 1852, Edward Leslie Molineuxstill three months shy of his nineteenth birthdaybegan what he called his scrapbook. It was not a pasted-in collection of newspaper and magazine clippings (though in later years, when his own name began to appear regularly in the press, he would assemble several of those, too). Rather, this ledger-sized volume was a handwritten miscellany of striking facts, inspirational sayings, and practical information on everything from military tactics to medicinal recipes.

Next page