Table of Contents

The author is grateful to the following rights holders for permission to reprint lyrics:

James David: Ill Never Fall in Love Again by Hal David and Burt Bacharach 1968 (renewed 1996) Casa David & New Hidden Valley Music. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Tim Rice: Circle of Life and Chow Down by Tim Rice. Used by permission.

Warner Bros. Publications U. S., Inc., Miami FL 33014:

Any Place I Hang My Hat Is Home by Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen 1946 (renewed) Chappell & Co. (ASCAP). All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Call Me Mister by Harold Rome 1946 (renewed) Warner Bros. Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

The Heather on the Hill by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe 1947 (renewed) Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe. World rights assigned to and administered by EMI U Catalog Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

New York, New York by Betty Comden, Adolph Green, Leonard Bernstein 1945 (renewed) Warner Bros. Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Night and Day by Cole Porter 1932 (renewed) Warner Bros. Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Old Devil Moon by E. Y. Harburg and Burton Lane 1946 The Players Music Group. renewed, assigned to Chappell & Co. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Speak Low by Ogden Nash and Kurt Weill. TRO 1943 (renewed) Hampshire House Publishing Corp. and Chappell & Co. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

When Im Not Near the Girl I Love by E. Y. Harburg and Burton Lane 1946 The Players Music Group. renewed, assigned to Chappell & Co. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

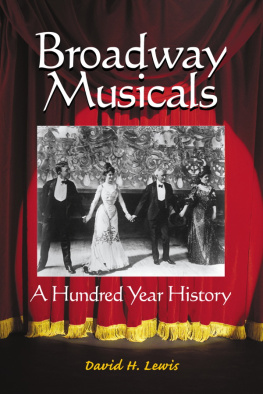

All photographs provided by Photofest.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Lewis, David H., 1940

Broadway musicals : a hundred year history / by David H. Lewis.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references, discography, and index.

ISBN 0-7864-1269-0

1. MusicalsUnited StatesHistory and criticism. I. Title.

ML2054 .L48 2002

782.1'4'097471dc21

2002009785

British Library cataloguing data are available

2002 David H. Lewis. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Left to right: George M. Cohan with sister Josie and parents Jerry and Nellie on Broadway (Photofest). Background 2002 Comstock.

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To

Abel Green

Preface

If I could have but one wish granted from the world of higher entertainment, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II would be back working on a new musical. I was lucky to be alive and attentive during the creation of their last four works. Still vivid are my recollections of advance news reports announcing subject matter, song titles, and stars signed. Still vivid are the first out-of-town reviews in Varietyin particular the one which began Sensational musical is on its way to Broadway when The Sound of Music opened in New Haven. How fond are my memories of waiting anxiously to hear the songs for the first time, staying tuned to the radio for new releases that might bear their titles.

Then the ultimate thrill: listening to the recorded score, usually on a Sunday evening broadcast a week or so before the original cast album arrived at our local record store. There, I savored its newness in my hands. Once home, the album was the star of the house, morning, noon and night. And what a glorious note the masters would go out on! I would live to see my high estimation of The Sound of Musictheir final opusrousingly affirmed forty years later when audiences attended sing-along versions of the movie.

How did such an addiction begin? As far as I can recall, it was one evening in Santa Rosa, California, in front of the old console radio in the bedroom I shared with my older brother, Dick, when I heard Mary Martin singing A Cockeyed Optimist from the original cast album of South Pacific. Something quite extraordinary happened, for my young ears were riveted to the artfully constructed verse and the haunting music. Perhaps at that fateful moment the elevated world of Broadway songwriting claimed a part of my soul.

It might have proved only a passing infatuation had not my brother, Dick, gone to San Francisco a few years later and been unexpectedly swept away by a touring production of Carousel. As a result, he started bringing home show albums. In retrospect, his keen enthusiasms seem to have helped nurture the seed that Mary, Dick and Oscar planted. What a time to fall in love with musical theatre. What a century. I am left with indelible memories of a greatness not guaranteed every age.

Those years of enchanted craftsmanship would not last forever. No golden age does. I had grown up during the last act, and it would take me many years to realize and appreciate that the first act had been even better. By that time, I had learned to endure something even more dispiriting than the arguable decline in a great American art form: a suicidal cynicism among insiders and hard-core fans against postgolden age developments. Many who lived through the halcyon days would turn intolerant and bitter as the faces and voices of singing shows changed, unable or unwilling to allow the occasional new musical with valid offerings into their closed hearts. Yet I can tell you this: If my most thrilling moment was watching Mary Martin sing Im in Love With a Wonderful Guy when South Pacific played the Curran Theatre in San Francisco in 1957, probably the second greatest thrill was delivered from the same stage over forty years later when Petula Clark sang As If We Never Said Goodbye in a postgolden age show, Sunset Boulevard.

Perhaps the good new shows are fewer and farther between than they were in the 1940s and 1950s. Nonetheless, real musical theatre has not completely given way to mindless spectacle. Originality still struggles, now and then, to assert itself in fresh formats. And sometimes, still, the results can be compelling. If American writers lost their way the last quarter of the twentieth century, it was not for lack of a desire to experiment and extend or evenheaven, forbidto entertain.

Creative forces from foreign shores would come at least to their temporary if unwelcome rescue. For a number of years the names Andrew Lloyd Webber and Steven Sondheim were considered the only two options on Broadway. How sadly limiting that was; it surely took some kind of toll on alternative voices striving to break free of clich expectations. And truth be told, of late Broadway hasnt allowed in many new voices with strong visions of their own. When the producer assumes too much power over the act of creation itself, beware. Alan Jay Lerner was onto something when he wrote, The theatre flourishes when it is a writers theatre.

Once the final curtain falls and the lights and sets are struck, what remains are the cast albumsthe tangible and permanent reminders of variable fortunes along 42nd Street. Cast albums live on to charm and exhilarateand to annoy and irritate. We are confounded by the contradictory lessons they impart: How could such a marvelous set of songs have gone to bed with so dreadful a script? How could so legendary a success contain such mediocre words and music? We listen to magic and lament early closings. We endure banalities and are at a loss to understand why audiences rushed to embrace them in the first place. But those songs are only a fraction of what theatregoers experienced in the first placea mere echo of a long-lost enterprise whose particular makeup in all its complexities can never be recaptured. Such is the fleeting beauty of the living theatre.

Next page