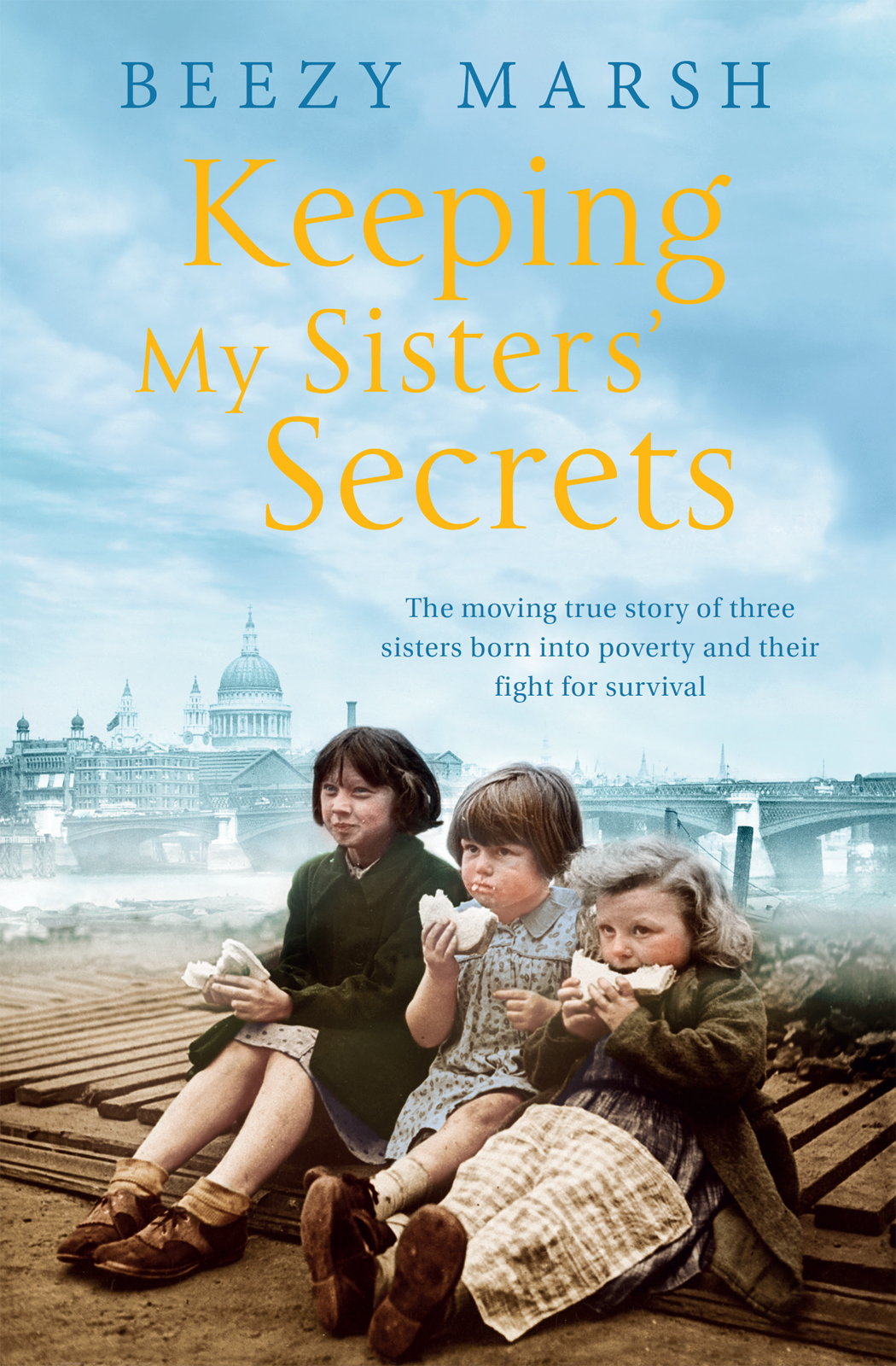

Keeping

my Sisters

Secrets

BEEZY MARSH

PAN BOOKS

To the memory of Londoners

who lost their lives in the Second World War.

Contents

Prologue

1931

The grimy streets of Lambeth, nestled beside the river Thames, had changed little since the days of Charles Dickens, when the poorest working classes lived cheek-by-jowl with thieves and drunkards. Women living there took in piece-work such as laundry or fur-pulling to help make ends meet, just as their mothers and grandmothers had done before them. Their husbands worked long hours, either in the factories as labourers, as costermongers or down at the docks. And that was if they were lucky enough to have their men in work. Families were large five or six children, or more and diseases including scarlet fever and diphtheria were fatal and much-feared. The threat of poverty was ever present but the temptation for husbands to drown their sorrows in one of the many local pubs could lead to the whole family being thrown out into the street when the rent- and tallyman came knocking for their dues.

These little rows of two-up, two-downs were tight-knit communities where scores were sometimes settled with fists. The police would only venture down there in pairs and rarely after nightfall when the dim glow of gaslight did little to illuminate pea-souper fogs. Yet for those growing up in this corner of Lambeth, the cobbled streets, the stench of the river, the shouts of the factory workers, the nosy neighbours and the rumble of the trains over at Waterloo meant one thing home.

This is the story of three sisters growing up in one such street, Howley Terrace, in the years between the wars. It is the story of their hopes and dreams and struggles for a better life when the odds were stacked against them.

This is the story of the Lambeth girls, Peggy, Kathleen and Eva, who learned to keep each others secrets in a bond of sisterhood, which even dire poverty, violence and war could not break.

Eva, May 1931

She didnt really mind getting up so early.

Eva could hear her father downstairs in the scullery, clattering about making himself a pot of tea before work. It was barely light outside but if he didnt leave the house soon, shed miss all the best buns at the bakery over in Covent Garden.

Eva waited until she heard him pulling on his boots and the front door slam shut before she forced her feet out of her warm nest in the flannelette sheets and onto the bare boards of the bedroom floor. Kathleen, her sister, lay next to her, soundly asleep. Her hair was tied in rags, which spread out on the pillow like little snakes. Mum didnt bother putting Evas hair in rags. Dead straight, like your fathers, she told her. Theres little or no point trying to make it curly. Kathleen, on the other hand, had near-perfect ringlets even without the help of mother and her nightly rag-ties. Eva toyed with the idea of yanking one of those raggy little tails but thought better of it. She didnt want to wake the whole street with Kathleens squealing.

Instead, Eva grasped her own thick, long black hair and tied it with a grubby ribbon before pulling on her pinafore and making her way out onto the landing. Mum, already dressed in her housecoat and slippers, was standing there, holding out a pillowcase for her.

Mind he doesnt see you, she whispered.

Eva took the pillowcase and nodded solemnly. If Dad knew what she was up to, it would earn her a belting, not that she cared. Shed felt the buckle end of his belt on more than one occasion. The welts went down after a while and all that remained was an empty feeling inside, which was worse than hunger. At least bread made her feel a bit better. Day-old bread from Godden and Hanken bakery was a mainstay of their diet and a cheap way for Mum to fill their rumbling bellies when the housekeeping was running short which was most of the time, these days. But Evas father wouldnt tolerate her queuing up for handouts with the children from the Thieves Kitchen of the Seven Dials, like some common urchin.

Eva was eight, nearly nine in fact, so she was too young to go out to work but she would have done if she could, just to help Mum. She was the youngest after Frank but was more daring than any of her brothers and sisters. Kathleen would soon be eleven and she should really have made the trip but liked her sleep too much to bother, same as her twin, Jim. Peggy was thirteen and would be leaving school in a year or so but she was a goody-two-shoes, Dads favourite, and wouldnt dare do anything to risk his anger.

The early mornings were making Eva tired and she was prone to catching forty winks in the afternoons during lessons. Her teacher at St Patricks had said as much when she met her mother on the Walworth Road last week: Eva really does need to get to bed earlier, Mrs Fraser!

Eva hurried down their tiny street, each house with the same two storeys of grimy bricks as the last, before turning left onto Waterloo Bridge. She knew the route by heart: up Bow Street, into Long Acre and over to Great Newport Street.

Flower sellers in long skirts and straw hats, their woollen shawls pulled tightly around their shoulders, were already at their pitches and the drunks from the night before were still lying in the gutter as Eva ran the last hundred yards to the bakery door. She was the last one there. A row of ragged children, some with dirty faces and no shoes, jostled in front of her, brandishing their pennies.

Eva drew herself up to her full height and flicked imaginary dust off her pinafore as she looked down her nose at them. Yes, she was poor but she was clean; Mum always made sure of that, even though Eva hated having her face wiped with a dishcloth before she left the house. The tin bath took pride of place in the scullery once a week and she got her turn in it. She scratched her head. Nits again, probably, but Mum would sort that out with a metal comb later. Eva winced at the thought of her hair being pulled and scraped. She sighed as she waited her turn, the penny in her hand growing sweaty. What if there was nothing left for her to take home?

Dad had a good job as a wood sawyer down at the cricket bat factory but with five of them to feed on wages of two pounds a week, there just wasnt enough to go around. It was all their mother could do to keep shoes on their feet. Frankies were full of holes, mainly because he was the youngest and got all the hand-me-downs. And that was before Mum got to paying out the insurances. Eva didnt fully understand what they were but it was to do with the hospital and teeth and the like. Mum said, Dont worry your head about it, chicken, but Eva did worry. Especially when she saw her mother twisting her thin gold wedding band round and round her finger and her eyes red-rimmed from crying when all the money had run out by Wednesday.

The insurances had seemed to go up after Frankie got run over by a lorry a couple of years back. Eva swallowed hard at the memory of it. She was supposed to be minding him while Mum went out to clean at one of the little hotels up by Waterloo Station to earn a few pennies more. She had another job in the mornings cleaning over at the Imperial Chemical Industries building but that didnt pay enough.

It had all happened so fast. They were playing in the streets with the other kids from Howley Terrace, larking about. Someone had a dog which had caught a rat and they poked at the dead body a bit with some sticks and watched it ooze blood. Massive teeth, said one boy. Like yer grandad! said Frankie, poking him in the ribs and making everyone hoot with laughter.

Frankie got bored of it all in the end. Kathleen turned her nose up and went to go skipping with Doreen from a few doors down. Peggy had her head stuck in a book, as usual, and was sitting on the front step, reading. Eva was only chatting to her pal, Gladys, for an instant about the new clothes her Nanny Day had knitted for her peg dolly, which made her look so pretty. Then she heard Frankie shout: Got any cards, mister? just as one of the lorries from the wastepaper factory at the top of the road came trundling past.