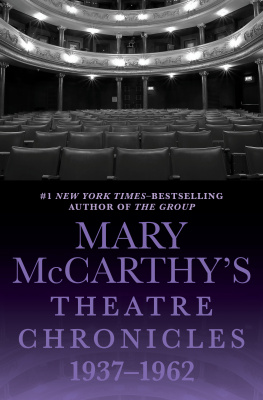

Intellectual Memoirs

New York 19361938

Mary McCarthy

FOREWORD

INTELLECTUAL MEMOIRS: NEW YORK 19361938. I look at the title of these vivid pages and calculate that Mary McCarthy was only twenty-four years old when the events of this period began. The pages are a continuation of the first volume, to which she gave the title: How I Grew. Sometimes with a sigh she would refer to the years ahead in her autobiography as I seem to be embarked on how I grew and grew and grew. I am not certain how many volumes she planned, but I had the idea she meant to go right down the line, inspecting the troops you might say, noting the slouches and the good soldiers and, of course, inspecting herself living in her time.

Here she is at the age of twenty-four, visiting the memory of it, but she was in her seventies when the actual writing was accomplished. The arithmetic at both ends is astonishing. First, her electrifying (to excite intensely or suddenly as if by electric shock) descent upon New York City just after her graduation from Vassar College. And then after more than twenty works of fiction, essays, cultural and political commentary, the defiant perseverance at the end when she was struck by an unfair series of illnesses, one after another. She bore these afflictions with a gallantry that was almost a disbelief, her disbelief, bore them with a high measure of hopefulness, that sometime companion in adversity that came not only from the treasure of consciousness but also, in her case, from an acute love of being there to witness the bizarre motions of history and the also, often, bizarre intellectual responses to them.

Intellectual responses are known as opinions and Mary had them and had them. Still she was so little of an ideologue as to be sometimes unsettling in her refusal of tribal reactionleft or right, male or female, that sort of thing. She was doggedly personal and often this meant being so aslant that there was, in this determined rationalist, an endearing crankiness, very American and homespun somehow. This was true especially in domestic matters, which held a high place in her life. There she is grinding the coffee beans of a morning in a wonderful wooden and iron contraption that seemed to me designed for muscle-buildinga workout it was. In her acceptance speech upon receiving the MacDowell Colony Medal for Literature she said that she did not believe in laborsaving devices. And thus she kept on year after year, up to her last days, clacking away on her old green Hermes nonelectric typewriter, with a feeling that this effort and the others were akin to the genuine in the artsto the handmade.

I did not meet Mary until a decade or so after the years she writes about in this part of her autobiographical calendar. But I did come to know her well and to know most of the characters, if that is the right word for the friends, lovers, husbands, and colleagues who made up her cast after divorce from her first husband and the diversion of the second John, last name Porter, whom she did not marry. I also lived through much of the cultural and political background of the time, although I can understand the question asked, shyly, by a younger woman writing a biography of Mary: Just what is a Trotskyite? Trotskyite and Stalinistpart of ones descriptive vocabulary, like blue-eyed. Trotsky, exiled by Stalin and assassinated in Mexico in 1940, attracted leftists, many of them with Socialist leanings, in opposition to the Stalin of the Moscow Trials, beginning in 1936, which ended in the execution of most of the original Bolsheviks and the terror that followed.

The preoccupation with the Soviet Union, which lasted, with violent mutations of emphasis, until just about yesterday, was a cultural and philosophical battleground in the years of Mary McCarthys debut and in the founding, or refounding, of the magazine Partisan Review. In that circle, the Soviet Union, the Civil War in Spain, Hitler and Mussolini, were what you might call real life but not in the magazines pages more real, more apposite, than T. S. Eliot, Henry James, Kafka, and Dostoyevski.

The memoir is partly ideas and very much an account of those institutional rites that used to be recorded in the family Bible: marriage, children, divorce, and so on. Mary had only one child, her son, Reuel Wilson, but she had quite a lot of the other rites: four marriages, interspersed with love affairs of some seriousness and others of none. Far from taking the autobiographers right to be selective about waking up in this bed or that, she tempts one to say that she remembers more than scrupulosity demandsdemands of the rest of us at least as we look back on the insupportable surrenders and dim our recollection with the aid of the merciful censor.

On the other hand, what often seemed to be at stake in Marys writing and in her way of looking at things was a somewhat obsessional concern for the integrity of sheer fact in matters both trivial and striking. The world of fact, of figures even, of statistics...the empirical element in life...the fetishism of fact...: phrases taken from her essay The Fact in Fiction (1960). The facts of the matter are the truth, as in a court case that tries to circumvent vague feelings and intuitions. If one would sometimes take the liberty of suggesting caution to her, advising prudence or mere practicality, she would look puzzled and answer: but its the truth. I do not think she would have agreed it was only her truthinstead she often said she looked upon her writing as a mirror.

And thus she will write about her life under the command to put it all down. Even the name of the real man in the Brooks Brothers shirt in the fiction of the same name, but scarcely thought by anyone to be a fiction. So at last, and for the first time, she says, he becomes a fact named George Black, who lived in a suburb of Pittsburgh and belonged to the Duquesne Club. As in the story, he appeared again and wanted to rescue her from New York bohemian life, but inevitably he was an embarrassment. As such recapitulations are likely to be: Dickens with horror meeting the model for Dora in later life. Little Dora of David Copperfield: What a form she had, what a face she had, what a graceful, variable, enchanting manner! Of course, the man in the Brooks Brothers shirt did not occasion such affirmative adjectives but was examined throughout with a skeptical and subversive eye. About the young woman, the author herself more or less, more rather than less, she would write among many other thoughts: It was not difficult, after all, to be the prettiest girl at a party for the share-croppers.

The early stories in The Company She Keeps could, for once, rightly be called a sensation: they were indeed a sensation for candor, for the brilliant lightning flashes of wit, for the bravado, the confidence, and the splendor of the prose style. They are often about the clash of theory and practice, taste and ideology. Rich as they are in period details, they transcend the issues, the brand names, the intellectual fads. In The Portrait of the Intellectual as a Yale Man, we have the conflict between abstract ideas and self-advancement, between probity and the wish to embrace the new and fashionable. About a young couple, she writes: Every social assertion Nancy and Jim made carried its own negation with it, like an Hegelian thesis. Thus it was always being said by Nancy that someone was a Communist but a terribly nice man, while Jim was remarking that someone else worked for Young and Rubicam but was astonishingly liberal.

Next page