Table of Contents

PENGUIN TWENTIETH-CENTURY CLASSICS

EARLY PLAYS OF EUGENE ONEILL

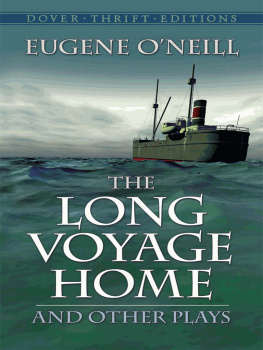

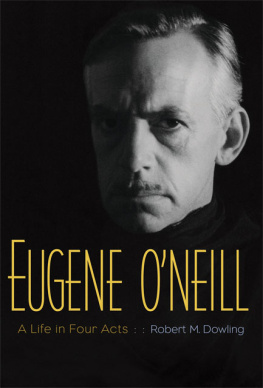

Eugene ONeill (1888-1953) is one of the most significant forces in the history of American theater. With no uniquely American tradition to guide him, ONeill introduced various dramatic techniques, which subsequently became staples of the U.S. theater. By 1914 he had written twelve one-act and two long plays. Of this early work, only Thirst and Other One-act Plays (1914) was originally published. From this point on, ONeills work falls roughly into three phases: the early plays, written from 1914 to 1921 (The Long Voyage Home, The Moon of the Caribbees, Beyond the Horizon, Anna Christie); a variety of full-length plays for Broadway (Desire Under the Elms; Great God Brown; Ah, Wilderness!); and the last, great plays, written between 1938 and his death (The Iceman Cometh, Long Days Journey Into Night, A Moon for the Misbegotten). Eugene ONeill is a four-time Pulitzer Prize winner, and he was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 1936.

Jeffrey H. Richards, professor of English at Old Dominion University, teaches early American literature and early through contemporary American drama. He is the author of Theater Enough: American Culture and the Metaphor of the World Stage, 1607-1789, and Mercy Otis Warren, and most recently the editor of Early American Drama, published in Penguin Classics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The editor wishes to thank the graduate students in his ONeill seminar at Old Dominion University, John Seelye, and Michael Millman for their critique and encouragement of the project; research assistants Ruth Barrineau Brooks and Elisabeth Simmons for their invaluable sleuthing of bibliographical items; and Stephanie Sugioka, Aaron Richards, and Sarah Richards for their unfailing support.

INTRODUCTION

The fame accorded to Eugene ONeill lies largely with his late plays, especially The Iceman Cometh (1940) and Long Days Journey into Night (1941), as well as those of his middle period, including Desire Under the Elms (1924), The Great God Brown (1925), and Strange Interlude (1927). Those plays were only made possible, of course, by the work he produced between 1913 and 1922, the first phase of his career as a playwright. For the most part, scholars have examined these early plays as material to be considered as predictive of the later, in the way that New Testament theologians often read the Old. Certainly, such reading of early into late is inevitable for readers of the whole corpus of ONeills work: one cannot help, for instance, but connect the barroom scene in Anna Christie to that in Iceman or see the family conflicts in Beyond the Horizon as harbingers of the Tyrones troubles in Long Days Journey. Unfortunately, such readings often obscure what ONeill was doing when plays like Ile or Moon of the Caribbees were the newest things he wrote, and critics were hailing him as the most innovative playwright in the American theater.

This volume brings to readers a selection of ONeills early work, written between 1914 and 1921 and produced for the stage between 1916 and 1922. The last play printed here, The Hairy Ape, was ONeills forty-first written dramaan enormous output of something like four plays a year from 1913. Indeed, by the time he wrote Bound East for Cardiff (1914), the earliest play in this Penguin edition, he had already written seven plays; the next earliest in this book, In the Zone (1917), was ONeills twenty-first. The point of such numbers is to suggest that even with much of his early work, ONeill was a practiced playwright, not simply an apprentice waiting to write A Moon for the Misbegotten (1943). Rather, he was a late Victorian who took the theater of his day and wrestled it into modes as yet unexploited or unexplored, producing dramas that still have the power to move and provoke. The challenge for readers and scholars of American drama is to be able to see these plays as something more than a source of motifs for the dramas of ONeills last years.

LIFE

Eugene Gladstone ONeill was born in a hotel in New York on October 16, 1888, the third child of Mary Ellen Quinlan and James ONeill. His father, a noted actor, had been born in Ireland and was making his career as the star of a vehicle play, Monte Cristo. His mother, daughter of an Irish-American merchant family from Cleveland, had difficulties during Eugenes birth and began taking morphine. She soon became addicted, unbeknownst to Eugene until he was a teenager, and only overcame the habit in 1914. A brother, Edmund, had died of measles before Eugene was born. His oldest brother, James Jr. (Jamie), became a member of his fathers acting company and took other bit roles in theatrical performances but led a dissolute life before dying in late 1923, at age forty-five. The transience of a life on the road with his father, the tensions in the family occasioned by his mothers addiction, and his brothers failure to make his mark would profoundly influence Eugenes dramatic thinking in later years.

ONeills scholastic career was checkered. Much of what he learned he picked up from acquaintances in New York City, including the radical politics of socialists and anarchists; the philosophy of Nietzsche; drama by Ibsen and later Strindberg; and poetry by the decadent writers Baudelaire, Dowson, Swinburne, and Wilde. Suspended after one year at Princeton University, ONeill lived a bohemian existence. An affair with Kathleen Jenkins in 1909 led to a secret marriage, then ONeills sudden departure on a mining trip to Honduras. When he returned stateside, after a bout with malaria, he shipped out on a sailing vessel, the Charles Racine, not bothering to visit his wife or new son, Eugene Jr. This trip took him to Buenos Aires, an experience that haunts the fringes of some of his early plays like a nightmare; eventually, he departed South America on board a British steamer, the Ikala, the model for the SS Glencairn in several plays. He returned to New York in April 1911, without any interest in taking up again with Kathleen.

The next five years would be greatly formative for ONeill the playwright. He lived for several months at a flophouse tavern run by James Jimmy the Priest Condon, fitting in last voyages as a seaman on the luxury liners New York and Philadelphia in 1911. After a suicide attempt at Condons in 1912, he spent more time with his parents in New London, Connecticut. The onset of tuberculosis led to commitment to a county sanatorium, then a private one, Gaylord, at the end of 1912. His months there, he said later, were the impetus to his becoming a playwright. Beginning with A Wife for a Life, ONeill took to writing one-act and a few full-length plays, publishing five of his one-acts in 1914. In that year, too, he entered Harvard as a special student in George Pierce Bakers English 47 class on playwriting, learning craft elements that remained with him his whole career. With his father in financial trouble, ONeill left Harvard after the spring 1915 term, and returned to New York, resuming such long-term bad habits as heavy drinking and consorting with prostitutes.

In the summer of 1916, ONeill and an anarchist friend, Terry Carlin, took a boat from Boston to Provincetown at the tip of Cape Cod. There he met a group of writers and actors, the Provincetown Players, who hoped to challenge what they saw as a moribund American theater through new, more intimate forms of presentation. Led by George Cram Cook, his wife Susan Glaspell, Neith Boyce, and her husband Hutchins Hapgood, the group attracted a number of talented, innovative writers and artists, including Louise Bryant, with whom ONeill would have an affair. For their second summer bill, played at the old wharf they had converted to a theater space, the group chose ONeills