All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America.

2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 10 9 87 6 5 4 3 2 1

Introduction

By the time I arrived in South Korea in 1996, this small East Asian nation had already pulled itself out of poverty and overcome its turbulent history to create a modern, middle-class nation. After twenty-five years of frenzied development, most of the major cities had taken shape, roads were laid out, and neighborhoods were well defined. All the really big changes had taken place.

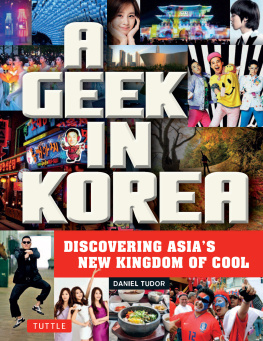

With, however, one major exceptionKoreas modern pop culture. The movie industry, music, comic books, television, and more all underwent complete transformations over the next decade. Through no design of my own, I was living there at the time and saw it all. In almost every genre, the changes to Koreas pop scene in the late 1990s and early 2000s were incredible.

When I first arrived in Korea, I taught English. When I asked my students for advice on what Korean movies to watch, I received a lot of embarrassed looks and hemming and hawing. Some students offered an opinion, even with enthusiasm. But I mostly heard embarrassed laughs and advice like, Its all bad. Music was a little different. The first dance-pop wave had already hit, with young people going crazy for Seo Taiji and Boys, and dance groups springing up like weeds after Koreas rainy season. Koreas television dramas were already established, although, as with music, almost no one outside Korea was aware of them. Comic books and animation were extremely popular, with Japan supplying the bulk of the materials.

From the beginning of my time in Korea, these were the aspects of Korea that fascinated me. I checked out what concerts I could find, and while most of them were bad heavy-metal hair bands, I did stumble across the quirky underground group Hwang Shin Hye Band at a tiny underground venue in western Daejeon. When I moved to Seoul, I was so impressed by the energy of the music and art scenes that not only did I want to learn more about them, I wanted to write about them, too. The great dance beats of Saebome Pin Dalgikkot. The bizarre trot parody of Bolbalkkan. The artists and quirky people who populated the bars and all-night establishments of the Hongik University neighborhood in western Seoul. Korea had been such a conservative, work-oriented culture for so long, there was a real sense in the 1990s that the arts and pop culture were driving a fundamental change, creating a new Korea. After a few stories for local English-language publications, gradually international newspapers and magazines started buying my articles. When I was lucky enough to stumble into Billboard and the Hollywood Reporter in 2002, a new career was born.

Today, the huge success of Korean pop culture is well known. At home, South Koreans watch far more of their own movies than Hollywood imports. They listen, dance, and rap to their own music far more than anything from the United States (or Europe or even Japan). Foreign programs have almost vanished from televisions regular, terrestrial channels, banished to the cable dial.

Abroad, Korean culture similarly caught on in ways no one could have predicted in the 1990s. In February of 2006, for example, giant posters of the Korean singer Rain blanketed the city of Bangkok, far more numerous and imposing than those for Franz Ferdinand or any Western act passing through. In March that year, in the hip Tokyo neighborhood of Roppongi, a new movie theater opened up, chiefly for Korean films. The newest, nicest movie theater in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, is run by a South Korean company and usually has at least one Korean film playing. In 2005, the biggest television hit in Hong Kong was not CSI or 24, but the Korean period drama The Jewel in the Palace; over 3 million of the citys 6.5 million residents tuned in to see the final episode. And a look around any black market in Asia will reveal an impressive collection of CDs, DVDs, and whathaveyou of South Korean content.

In short, at home, around Asia, and increasingly around the world, Korean movies, music, television dramas, comic books, and more are hot items, both artistically and commercially, winning awards and enthralling fans in ever-larger numbers.

So how did South Korea come to this special point? Who had a vision that Korean culture could compete on the world stage? What was special about Korea and Koreans that enabled them to go toe-to-toe with Hollywood and the Western entertainment machine, which has overwhelmed almost every other culture around the world? What allowed them to compete with Japanese pop culture, which exerts a huge influence around Asia?

Korean History: A Primer

Koreas artistic traditions date back centuries and mirror its long and often turbulent history. Most historians think Koreans are probably descended from the people of Mongolia, but China has been the dominant influence over the centuries. Culturally, Koreas oldest traditions are shaman in origin, with China adding Confucianism and Taoism first, then Buddhism in the fourth century.

The first major government in what is now Korea was called Gojoseon, dating back to 2333 BC according to myth, but more likely, the Gojoseon government developed into a state from the seventh to fourth centuries BC. Gojoseon gave way to the Three Kingdoms period in the first century BC, with Goguryeo in the north, Baekje in the southwest, and Silla in the southeast. In the seventh century, Silla teamed up with China to take out its rivals and unite the Korean peninsula. That was followed by the Goryeo dynasty in 918, and the Joseon dynasty in 1392 (also written Chosun in another Romanization system). The Joseon ruled Korea until Japan colonized the peninsula in 1910.

The Dear Director

Kim Jong-il, leader of North Korea, has long been reputed to be an avid film fan, owning over 20,000 videotapes (no word on his DVD collection). He even wrote On the Art of the Cinema, the ultimate book on filmmaking (well, if you are a North Korean filmmaker).

The Joseon dynasty began with an incredible flourishing of creativity. Most famously, King Sejong led the creation of hangul, the Korean writing system, unveiled in 1446. Although originally considered only for the vulgar classes and women, and not widely used until the twentieth century, hangul was nonetheless an impressive achievement. Koreans still take great pride in their writing system.

The thirteenth to the sixteenth century in Korea was a fruitful time for many inventions and innovations. Koreans invented, in addition to hangul, the metal, movable-type press around 1234, years before Gutenberg. (Unfortunately, no one in Korea or China invented the mechanized press, making their inventions much less efficient than the Gutenberg press, which is why Korean and Chinese presses never caught on and revolutionized their worlds.) Koreans were, at the time, one of the foremost masters of astronomy in the world. Water clocks, rain gauges, sundials, and many other technical achievements mark the period.