Copyright 2016 by TwoDeeTV

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

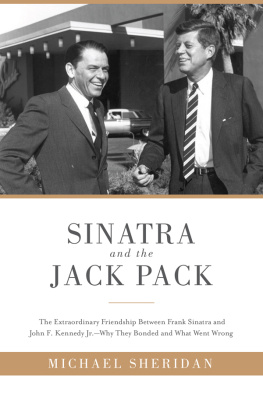

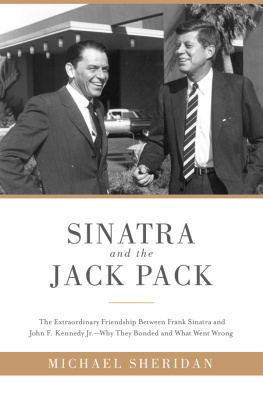

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Front cover photograph: AFP

Print ISBN: 978-1-51070-362-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-51070-371-1

Printed in the United States of America

For a comprehensive bibliography, please visit www.circlefilms.tv/jackpack.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1: The Beginnings

15 MONROE STREET was an unremarkable building on an unremarkable street in the unremarkable town that is Hoboken, New Jersey. A four-story tenement surrounded by many of similar size and some much smaller, one and two story, the sort of buildings that defined the immigrant communities that grew up on both sides of New Yorks Hudson River in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From the top of the building, located just twelve blocks from the shoreline, you could see the three churches of St. Ann, St. Francis, and Our Lady of Grace and St. Joseph, established in the area to cater to the optimistic Catholic emigrants who had streamed into the town hoping for a new life in America. Beyond these places of worship was the growing skyline of Manhattan, where some of the neighborhoods residents traveled daily to try to make a living.

For many people, the American dream had come to a crashing halt in Hoboken, just five miles from where they had entered the United States at Ellis Island, the nations busiest immigration inspection station from around the turn of the nineteenth century. For Italian peasants from as far apart as the picturesque shores of Lake Como in northern Lombardy to the arid and tiny towns of Ragusa in southern Sicily, the hope of wealth and prosperity had given way to the harsh reality of life at the bottom of the immigrant ladder in the New World. At the time, German merchant classes occupied the top rung, a trend that would decline rapidly as a result of anti-German sentiment at the outbreak of World War I. Their dominance was followed by the Irish, who controlled the police and fire services, leaving the scraps for the Italians, many of whom arrived in the country without papers, prompting the denigrating nickname WOP.

Saverio Antonino Martino Sinatra was just twelve when he passed through the Ellis Island inspection in 1904 with his mother, Rosa, and his sisters, Angela and Dorotea. Francesco, his father, had traveled ahead and was already working in a pencil factory when his family arrived. Rosa appears not to have considered education essential to her sons advancement, and Saverio, who had adopted the more Americanized moniker of Marty, remained illiterate. First apprenticed as a shoemaker, he turned in his late teens to prizefighting, adopting the pseudonym Marty OBrien, possibly to ingratiate himself with the Irish locals but more likely because Italians were not allowed in the fight game. Marty had tattoos drawn all over his arms, but with a slight build and an asthmatic condition, he did not come across as fearsome or threatening, neither to his opponents nor to the local street gangs. He was also too laid back in personality to make any impact either in, or outside, the ring.

He had, however, made an impact on Natalie Dolly Garavente, another Italian immigrant who lived nearby. Dolly had left the town of Rossi in Liguria, northern Italy in the late 1800s and had settled with her family in Hoboken. Dolly and Marty had been seeing each other since late 1910, when she had just turned fifteen and he was eighteen, and Dolly would dress up in her brothers clothes, hair bunched up under his cap, to go to Martys bouts in a time when women were not allowed at boxing matches. Dollys brother, Dominick, was also a disguised Italian fighter and regular opponent of Martys.

The Ligurian Garaventes had little time for the Sicilian Sinatras and regarded the illiterate Marty as highly unsuitable for the daughter of a family keen on bettering itself. As a result, Dollys parents refused to countenance the relationship. When the Garaventes refused point blank to host a wedding, Dolly and Marty eloped. The most romantic destination within their means was Jersey City, four miles down the road, and it was there, in the city hall, on Valentines Day 1914, that they were married. The bridegrooms occupation was registered as athlete, and the couples friends Anna Caruso and Harry Marrotta witnessed the ceremony. It was a tribute to Dollys courage to go down this path without her parents blessing and against the background of the importance of the act of marriage in the staunchly Catholic ethos of Italian culture, and all the more so among the immigrant community. It was also a vote of confidence in Marty who, although kind and decent in every respect, did not engender much confidence as a potential breadwinner. The couple would not starve though, because of the money Dollys mother made at her grocery store. But they had two great assets, the bond that had kept them together and Dollys ambition and maturity beyond her tender years.

When the dust from the secret wedding eventually settled, Dollys parents grudgingly accepted the union and the couple settled on Monroe Street. It was in a small, dark room of the tenement house, on December 12 of the following year, that the most life-changing event of the young couples lives was to occur. Dolly had become pregnant in the late spring, and as she began her labor the local midwife attended her, as was the custom in the community. Professional medical care was beyond the means of most, and with her sister and mother by her side, Dolly knew she would be delivering her baby with the most experience and attention at hand that she could hope for. After hours of labor, things seemed to stop abruptly, and Dolly was suddenly in great distress. This was most likely because at less than five feet in height, she had a small pelvic area, and the baby was so large that she couldnt push any longer because of exhaustion. At once, everyone in the room became increasingly worried by the progress of the birth. Sensing danger and realizing that the solution was beyond her skills, the midwife called the local doctor. Ten minutes later he arrived, quickly recognized that this had to be a forceps procedure, and literally ripped the baby from the exhausted mothers womb. The action, however crude, had been a matter of life and death. The doctor had not had time for niceties, knowing full well the potential consequence of two deaths as opposed to one. Safely delivering the child while making sure the mother survived was his priority in a time when infant mortality was extremely high.