For my mother, whose interest in everything

turned out to be the greatest gift

Contents

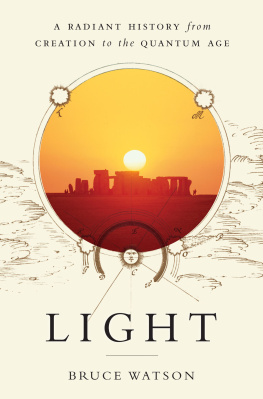

:

Myths of Creation and First Light

:

Early Philosophers from Greece to China

:

The Millennium of Divine Radiance

:

Islams Golden Age

:

Paradise in the Middle Ages

:

Light and Dark on Canvas

:

The Scientific Revolution and the Century of Celestial Light

:

Isaac Newton and Opticks

:

The Romantics and the Light Seductive

:

Particle vs. Wave

:

Frances Dazzling Century

:

Electricity Conquers the Night

:

Lasers and Other Everyday Wonders

We eat light, drink it in through our skins.

JAMES TURRELL, LIGHT AND SPACE ARTIST

Galileo was bewildered. Toward the end of his life, a life that had witnessed wondrous light that none had seen before, the great scientist confessed one failure. Decades had passed since a friend had given him several of the stones Italians called solar sponges. Soaking up sunlight, emitting a soft green glow, the stones convinced Galileo that Aristotle had been wrong about light. It was not a warm, ethereal element. Light could be as cold as the moon and as corporeal as water. But what was it?

Over the years, Galileo had learned to reflect light, to bend it, to amaze observers with telescopes that spotted ships two hours sail from Venice. Turning his telescope toward the night sky, he had been the first to see the moons of Jupiter and identify craters on the moon. Later he proposed the first experiment to clock the speed of light, bouncing lantern beams across the hilltops of Tuscany. Galileo never conducted his speed test. Other experiments, other trials, demanded his attention, yet he continued to wonder about light. Shortly before his death, blind and broken, he admitted how he longed for an answer. Though under house arrest for heresy, he said he would gladly suffer a harsher imprisonment. He would live in a cell with nothing but bread and water if, upon emerging, he could know the truth about light.

The truth is that, despite three millennia of investigation by humanitys most brilliant detectives, light refuses to surrender all its secrets. As familiar as our own faces, light is the first thing we see at birth, the last before dying. Some, having seen a warm glow as they flirted with death, swear that light will welcome us to another life. Painting is light, the Italian master Caravaggio noted, and each day light paints a mural that sweeps around the globe, propelling us into the morning. Ever since the Big Bang, light has been stealing the show. And for countless scientists, philosophers, poets, painters, mystics, and anyone who ever stood in awe of a sunrise, light is the show.

If there is magic on this planet, the naturalist Loren Eiseley wrote, it is contained in water. Light, however, is the magician of the cosmos. Light makes darkness vanish and worlds reappear. Light opens each day with a blaring overture, then throws its wands to earth and casts diamonds on lakes and oceans. Each night, lights tricks make the stars seem alive. Seen through telescopes Galileo could never have imagined, light dances across the rings of Saturn, shapes gas clouds into crabs and horse heads, spirals from great galaxies and bursts from newborn stars. As reliable and relentless as time, light will begin tomorrow with another hurrah, then close the show with house lights, low and glimmering. Drawn to it as surely as any moth, we cannot live without it. When the great night comes, everything takes on a note of deep dejection, the psychologist Carl Jung wrote, and every soul is seized by an inexpressible longing for light.

But what is light? What meaning have our brilliant detectives found in it? Is it God? Truth? Mere energy? Since the dawn of curiosity, these questions have been at the core of human existence. The struggle for answers has given light a history of its own. In human consciousness, light first appeared in stories of creation, stories spun in the glow of firelight or torch. From the immortal Let there be light of Genesis to the Icelandic edda that had God throwing embers into the darkness, light is the primal ingredient of every creation story. Following its mythical creation, light matured into a mystery that intrigued philosophers from Greece to China. Was light atoms or shimmering eidola? Were we all, as the Apostle Paul wrote, children of light? Just when each sage had light pinned down, the mystery rose again, posing further questions, fresher metaphors.

Light was Jesus (I am the light of the world). No, it was Allahthe Light of the heavens and the earth. No, it was the Buddha, also called Buddha of Boundless Light, Buddha of Unimpeded Light, Buddha of Unopposed Light Light was inspirationinner light. Light was love (the light in her eyes). Light was sexdivine coupling, according to Tantric Buddhism, fills sexual organs with radiance. Light was hope, thought, salvation (seeing the light). Dante filled his Paradiso with the heaven of pure light. Shakespeare toyed with it: Light, seeking light, doth light of light beguile. The blind poet Milton was obsessed with light: Hail, holy light, offspring of Heavn first-born. Caravaggio and Rembrandt captured light as a sword cutting through the blackness. Vermeer sent it streaming through windows. Beethoven heard it as French horns. Haydn preferred an orchestras full blare. Meanwhile, ordinary people spoke of the light of freedom, the light of day, the light of reason, the light of their lives

Yet from the first theories about its origin, light sparked bitter disputes. The earliest philosophers quarreled about lightwas it emitted by the eye or by every object? Holy men debated whether light was God incarnate or merely His messenger. And then there was lights handmaidencolor. Was it innate in each object or merely perceived by the eye? While some debated, others celebrated in festivals of light ranging from Hanukkah and winter solstice to the Hindu Diwali and the Zoroastrian Nowruz. Meanwhile, without the slightest concern for science or religion, sunrise and sunset circled the planet, rarely disappointing those who paused to admire.

Traced from creation to the quantum age, lights trajectory suggests that the miracle has lost some luster. Once we spoke of the light fantastic, but now we find light cheap and easy, available not just in every home and office but in every palm and pocket. Artificial light once came from precious few sourcescandles, lamps, and torches. But with lighting now a $100 billion industry, beams shoot out of bike helmets, key chains, shower heads, e-readers, smartphones, tablets, and dozens more devices. Light has become our most versatile tool, healing detached retinas, reading bar codes, playing DVDs. Light from liquid crystal displays brings us the World Wide Web. Light through fiber-optic cables carries the messages that girdle the planet. Thus we have made light as common as breath, as precise as a laptop.

But there was a time when light waged a heroic battle with darkness. It was a time when night skies were not bleached by urban glare, when candles were not romantic novelties, when light was the source of all warmth and safety. For the vast majority of human history, each sunrise was a celebration; each waxing moon stirred hope of nights less terrifying. And to anyone caught unpreparedin dark woods, on echoing streets, even at home when lamps flickered and failedlight was, simply, life. Unlocking its secrets required an uncommon set of keys. Curiosity. Persistence. Mirrors, prisms, and lenses. Through the centuries, as civilizations took turns asking and answering, the keys passed from Greece to China to Baghdad, from medieval France to Italy and back. When the keys came to Isaac Newton, his answers spread to the world, unlocking secrets we are still exploring.

Next page