Stories of Famous Regiments by Philip Warner

Index Of Contents

Introduction

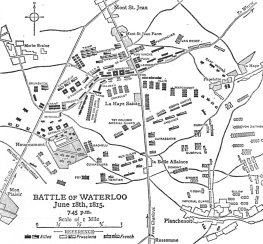

Chapter 1 - The Napoleonic Wars

Quatre Bras

Albuera

Vitoria

Chapter 2 - Actions in the Crimea

Balaclava

The Royal Sappers and Miners at Sebastopol

The Naval Brigade at the Redan

Chapter 3 - The Last Eleven at Maiwand

Chapter 4 - The South Wales Borderers at Isandhlwana

Chapter 5 - The Battle of Abu Klea

Chapter 6 - The Battle of Omdurman

Chapter 7 - The 2nd Devons at Bois des Buttes

In Billets

At Bois des Buttes

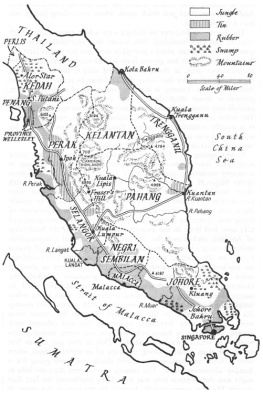

Chapter 8 - The Punjabis

Chapter 9 -The SAS

Maps

Picture Gallery

Philip Warner A Short Biography

Philip Warner A Concise Bibliography

Introduction

This book includes but a small number of the many hundreds of feats of outstanding bravery performed by British soldiers. Some are well known, some scarcely known at all, and yet others have never been recorded, apart from a bare mention in a regimental diary. Equally, some of the regiments are world famous; others have disappeared in a welter of amalgamations, although it is still possible (usually) to trace one battalion - or even company - which is a direct descendant of a much larger and more renowned predecessor. One fact will sing out like a trumpet to those who read this book and that is whatever the century, whatever the country, and whatever the task, the British soldier is second to none. There are brave men in all countries and not only brave men but enduring, flexible, ingenious, and resilient men too; however, in the annals of history the British soldier has a record which is unsurpassed. It will not escape the readers notice that for a regiment to perform a brave deed it needs first-class, or at least plentiful, opposition. A regiment can only prove itself in daunting circumstances; every tribute to a British regiment in this book in greater or lesser degree reflects some credit on its opponents.

Regiment is a broad term. It is best understood by taking a quick look at its origins. With the development of gunpowder in the sixteenth century the army was loosely organized into a number of companies of varying strength, some with as few as a hundred and fifty men; others with double that number. Each company had a colour or ensign and in later military history we often find accounts of stirring action to save a colour or to capture one from the enemy. There was, of course, nothing new in the sacred nature of the colour. Throughout history it has been the hope and rallying point of the unit and men have not hesitated to sacrifice their lives to preserve it.

Experience showed that if several companies were grouped together this formed a convenient battle unit. Such groupings were called regiments, and numbered up to three thousand men; companies, however, still carried their own colours.

In the sixteenth century, when Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden was organizing his army with great skill, it was noted that his regiments did not exceed a thousand in number. His organization was soon copied by other nations, including our own. The new units, which usually consisted of ten companies of one hundred men each, were commanded by a colonel. His second-in-command was called the sergeant-major but later this became major. Sergeant-major reappeared later as a non-commissioned rank. As more men were needed for various wars, second regiments were raised. These became known as the 2nd . In the present century, principally in the First World War, regiments were rapidly expanded; in the infantry the extra regiments were known as battalions and one regiment acquired forty-two. Specialist arms were usually called corps although some of these, such as the Kings Royal Rifle Corps, were really regiments. At the other end of the scale was the Royal Regiment of Artillery, which ultimately became enormous and consisted of regiments within a regiment, for instance, 15 Field Regiment. For most of the actions in this book it may be assumed that the deeds described were performed by a part of a regiment, whether or not it was designated as such at the time. Sometimes a number of small detachments from different units would make up a balanced force. The Light Brigade which charged in the Crimean War was less than three-quarters of the strength of a normal regiment; the term brigade now means a group of three regiments. Obviously numbers vary from time to time to meet operational requirements - or even changes in recruiting - and present-day numbers are no guide to the formations of the past.

Unfortunately efficiency has not been the main reason for the reshaping of the regimental system. The combination of apparent economy and tidier planning has swept away many a regimental name which once stirred the blood. This is no place to comment on present-day organization other than to say that the lesson of military history has been that a man tended to perform better in an easily recognizable and memorable unit than in a large organization composed of several extinguished regiments with no clear territorial association or historically renowned number. It would be invidious to mention names but readers of the following pages may sometimes look for a famous regiment among modern army lists - and look in vain. To quote but one - where is the Rifle Brigade? It does in fact exist: it is the third battalion of the Royal Green Jackets but for a time it did not exist at all.

And now to the actions that made some of the living and dead regiments famous.

Chapter I

The Napoleonic Wars

QUATRE BRAS

The length and impact of the Napoleonic wars is, not surprisingly, little known nowadays. But one hundred and fifty years ago it was appreciated well enough by people who were still suffering from the after effects. The war with France had begun in 1793 and it continued with short breaks until 1815. During that period there were several terrifying disasters and it often seemed that England might lose the war. The worst stage of the war was from 1803 to 1815. For the first two and a quarter years of that period Napoleon had 120,000 men on the French coast with a flotilla of boats, waiting to invade this country.

In a war of such size there were inevitably many heroic actions. One of these concerns the Rifle Brigade. In 1801 a group of riflemen was formed to experiment with the new Baker rifle. The rifle was modelled on the Hessian weapon and produced by a Whitechapel gunsmith. It had a range of three hundred yards, fired one round a minute, and had a twenty-three-inch-long bayonet. The regiment, then known as the 95th, wore a green uniform like that of gamekeepers. The colonel of the regiment, Colonel Coote Manningham, trained his men to be self-reliant, enduring and able to move and fight in small groups.

In the second battalion was a young officer, Captain Sir John Kincaid. In 1811 he was in the Peninsula campaign. On 12 March Massena was retreating and Wellington was following him up closely.

Kincaid wrote of his experiences at this time in the first extract given here.

Later Kincaids regiment was in Belgium. Napoleon had escaped from Elba and rejoined a now revitalized French army.

On 15 June 1813 he advanced on allied armies in Belgium. Blucher had 80,000 men but Wellington had only 7,000 (to confront 19,000 French). Napoleon beat Blucher at Ligny, then turned on Wellington at Quatre Bras. Before the end of the fighting Wellington had acquired substantial reinforcements but his victory was due to skill and not to numbers...

I was one of a crowd of skirmishers who were enabling the French ones to carry the news of their own defeat through a thick wood, at an infantry canter, when I found myself all at once within a few yards of one of their regiments in line, which opened such a fire, that had I not, rifleman like, taken instant advantage of the cover of a good fir tree, my name would have unquestionably been transmitted to posterity by that nights gazette. And, however opposed it may be to the usual system of drill, I will maintain, from that days experience, that the cleverest method of teaching a recruit to stand at attention, is to place him behind a tree and fire balls at him; as, had our late worthy disciplinarian, Sir David Dundas, himself, been looking on, I think that even he must have admitted that he never saw any one stand so fiercely upright as I did behind mine, while the balls were rapping into it as fast as if a fellow had been hammering a nail on the opposite side, not to mention the numbers that were whistling past, within an eighth of an inch of every part of my body, both before and behind, particularly in the vicinity of my nose, for which the upper part of the tree could barely afford protection.

Next page