Winston S. Churchill - Great Contemporaries: Savinkov & Trotsky (post-1937 omission)

Here you can read online Winston S. Churchill - Great Contemporaries: Savinkov & Trotsky (post-1937 omission) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 1937, publisher: Thornton Butterworth Ltd., genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Great Contemporaries: Savinkov & Trotsky (post-1937 omission)

- Author:

- Publisher:Thornton Butterworth Ltd.

- Genre:

- Year:1937

- City:London

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Great Contemporaries: Savinkov & Trotsky (post-1937 omission): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Great Contemporaries: Savinkov & Trotsky (post-1937 omission)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Winston S. Churchill: author's other books

Who wrote Great Contemporaries: Savinkov & Trotsky (post-1937 omission)? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Great Contemporaries: Savinkov & Trotsky (post-1937 omission) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Great Contemporaries: Savinkov & Trotsky (post-1937 omission)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

'How do you get on with Savinkov' I asked M. de Sazonov when we met in Paris in the summer of 1919.

The Czar's former Foreign Minister made a deprecating gesture with his hands.

'He is an assassin. I am astonished to be working with him. But what is one to do? He is a man most competent, full of resource and resolution. No one is so good.'

The old gentleman, grey with years, stricken with grief for his country, a war-broken exile striving amid the celebrations of victory to represent the ghost of Imperial Russia, shook his head sadly and gazed upon the apartment with eyes of inexpressible weariness.

'Savinkov. Ah, I did not expect we should work together.'

*****

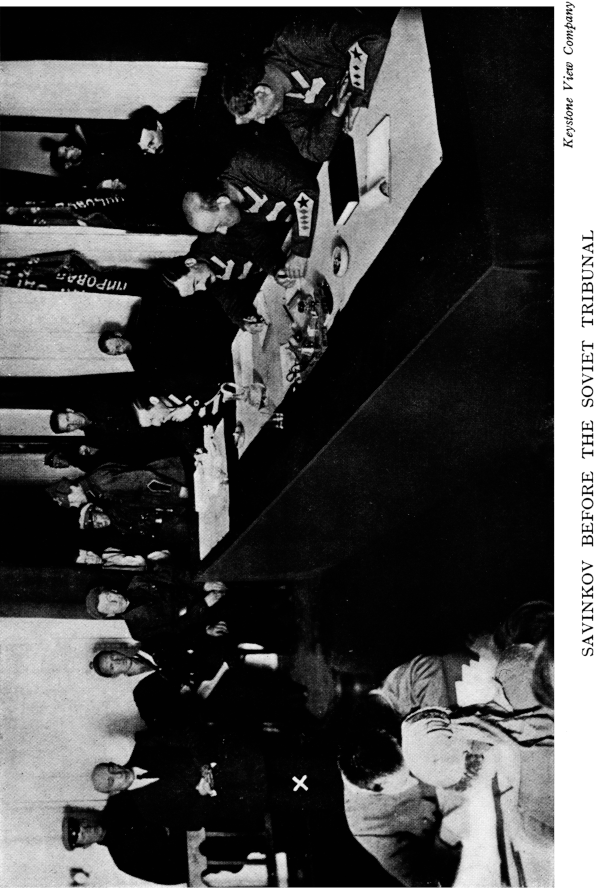

Later on it was my duty to see this strange and sinister man myself. The 'Big Five' had just decided to support Koltchak, and Boris Savinkov was his accredited agent. I had never seen a Russian Nihilist except on the stage, and my first impression was that he was singularly well cast for the part. Small in stature; moving as little as possible, and that noiselessly and with deliberation; remarkable grey-green eyes in a face of almost deathly pallor; speaking in a calm, low, even voice, almost a monotone; innumerable cigarettes. His manner was at once confidential and dignified; a ready and ceremonious address, with a frozen, but not a freezing, composure; and through all the sense of an unusual personality, of veiled power in strong restraint. As one looked more closely into this countenance and watched its movement and expression, its force and attraction became evident. His features were agreeable; but though still only in the forties, his face was so lined and crow's-footed that the skin looked in placesand particularly round the eyesas if it were crinkled parchment. From these impenetrable eyes there flowed a steady regard. The quality of this regard was detached and impersonal, and it seemed to me laden with doom and fate. But then I knew who he was, and what his life had been.

Boris Savinkov's whole life had been spent in conspiracy. Without religion as the Churches teach it; without morals as men prescribe them; without home or country; without wife or child, or kith or kin; without friend; without fear; hunter and hunted; implacable, unconquerable, alone. Yet he had found his consolation. His being was organized upon a theme. His life was devoted to a cause. That cause was the freedom of the Russian people. In that cause there was nothing he would not dare or endure. He had not even the stimulus of fanaticism. He was that extraordinary producta Terrorist for moderate aims. A reasonable and enlightened policythe Parliamentary system of England, the land tenure of France, freedom, toleration and goodwillto be achieved whenever necessary by dynamite at the risk of death. No disguise could baffle his clear-cut perceptions. The forms of government might be revolutionized; the top might become the bottom and the bottom the top; the meaning of words, the association of ideas, the rles of individuals, the semblance of things might be changed out of all recognition without deceiving him. His instinct was sure; his course was unchanging. However winds might veer or currents shift, he always knew the port for which he was making; he always steered by the same star, and that star was red.

During the first part of his life he waged war, often single-handed, against the Russian Imperial Crown. During the latter part of his life, also often single-handed, he fought the Bolshevik Revolution. The Czar and Lenin seemed to him the same thing expressed in different terms, the same tyranny in different trappings, the same barrier in the path of Russian freedom. Against that barrier of bayonets, police, spies, gaolers and executioners he strove unceasingly. A hard fate, an inescapable destiny, a fearful doom! All would have been spared him had he been born in Britain, in France, in the United States, in Scandinavia, in Switzerland. A hundred happy careers lay open. But born in Russia with such a mind and such a will, his life was a torment rising in crescendo to a death in torture. Amid these miseries, perils and crimes he displayed the wisdom of a statesman, the qualities of a commander, the courage of a hero, and the endurance of a martyr.

*****

In his novel, The Pale Horse, written under an assumed name, Savinkov has described with brutal candour the part he played in the murder of M. de Plehve and Grand Duke Serge. He depicts with an accuracy that cannot be doubted the methods, the daily life, the psychological state and the hair-raising adventures of a small group of men and women, of whom he was the leader, working together for half a year in mortal pursuit of a High Personage. From the moment when, posing as a British subject with a passport signed by Lord Lansdowne in his pocket and 'three kilograms of dynamite under the table', he arrives in the town of N., till the murder of 'the Governor' who is blown to pieces in the street, and the death, execution or suicide of three out of his four companions, all is laid bare. Most instructive of all is the account given by implication of the relations of the actual Terrorists with the Nihilist Central Committee who lay deep and secure in the underworld of the great cities of Europe and the United States.

'M. le Ministre,' he said to me, 'I know them well, Lenin and Trotsky. For years we worked hand in hand for the liberation of Russia. Now they have enslaved her worse than ever.'

Between Savinkov's first forlorn war against the Czar and his second against Lenin there was a brief but remarkable interlude. The outbreak of the Great War struck Savinkov and his fellow revolutionary, Bourtzev, in exactly the same way. They saw in the cause of the Allies a movement towards freedom and democracy. Savinkov's heart beat in sympathy with the liberal nations of the West, and his ardent Russian patriotism, put to the test, sundered him from the cold Semitic internationalists with whom he had been so long associated. Even under the Czar, Bourtzev was invited back to Russia, and threw himself into the task of national defence. Savinkov returned with the Revolution. In June, 1917, he was appointed by Kerensky, then Minister for War, to the post of Political Commissar of the 7th Army on the Galician front. The troops were in mutiny. The death penalty had been abolished. German and Austrian agents had spread the poison of Bolshevism through the whole Command. Several regiments had murdered their officers. Discipline and organization were gone. Equipment and munitions had long been lacking. Meanwhile the enemy battered ceaselessly on the crumbling front.

Here was the opportunity for his qualities. No sincere revolutionary could impugn his blood-dyed credentials of Nihilism. No loyal officer could doubt his passion for victory. And when it came to political philosophy and the interminable arguments with which the Russians beguiled the road to ruin, there lived no more accomplished student or devastating critic of Karl Marx than the newly-appointed Commissar. Alone, though not unarmed, he visited regiments who had just killed their officers, and brought them back to their duty. One one occasion he is reported to have shot with his own hand the delegates from a Bolshevik Soldiers' Council who were seducing a hitherto loyal unit. Meanwhile his organizing gifts amid a thousand difficulties repaired the administrative structure. In a month he had put a new heart into the discouraged Army Commander and his staff, and had so far redisciplined the Army as to enable it to take the offensive and win a notable action at Brzezany early in July.

Kerensky, becoming aware of Savinkov's good work, having himself seen evidence of it on a visit to the 7th Army front, appointed him forthwith Chief Commissar for the Army Group of the South Western front, then commanded by General Gutor. Savinkov had no sooner reached the scene than the front was broken by the Germans at Tarnopol (July 16-19, 1917). The military disaster was followed by wholesale desertions to the enemy, mutinies, massacres of officers and widespread revolt among the civil population. At the instance of Savinkov, Gutor was replaced on the 20th July by General Kornilov. We now approach one of the great mischances of Russian history. In Kornilov Savinkov believed that he had found the man who was to be the complement to his own character, a simple, obstinate soldier, popular among officers and men, with rigid views upon discipline, with no class prejudices, a sincere love of Russia and a knowledge of how to carry through schemes propounded by others. The time had come for a strong and ruthless hand, preferably corporate, if the Army was to be steadied and the country saved. Together with Kornilov, who in all Army matters shared his views, Savinkov demanded the reimposition of the death penalty for cowardice, desertion or espionage, both behind the line and among the fighting troops. Kerensky thus had at his disposal at this most fateful moment in Russian destinies both the political and the military man of action whom the crisis demanded; and both these men were heart and soul together. Here already at the summit of power was the triumvirate that could even at the eleventh hour have saved Russia from the awful fate which impended, which could have gained at a stroke both Russian victory and Russian freedom. Those who united could have retrieved all were in the event destroyed separately.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Great Contemporaries: Savinkov & Trotsky (post-1937 omission)»

Look at similar books to Great Contemporaries: Savinkov & Trotsky (post-1937 omission). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Great Contemporaries: Savinkov & Trotsky (post-1937 omission) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.