Contents

Eora people asked the question,

Waube-rong orab,

Where is a better country?

This thief colony might hereafter become a great empire,

whose nobles will probably, like the nobles of Rome,

boast of their blood.

The Morning Post, LONDON,

1 NOVEMBER 1786

authors note

I have taken the liberty in quotations from historic sources to standardise spelling, and in cases of misspellings left intact, to avoid the use of the mannerism [sic]. Any insertions I have made for the sake of clarifying the intentions of the original writers are signalled by square brackets.

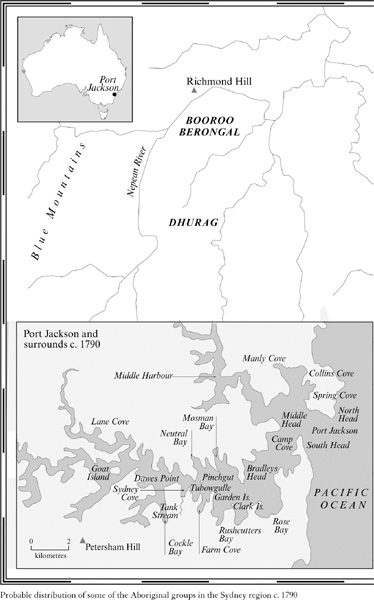

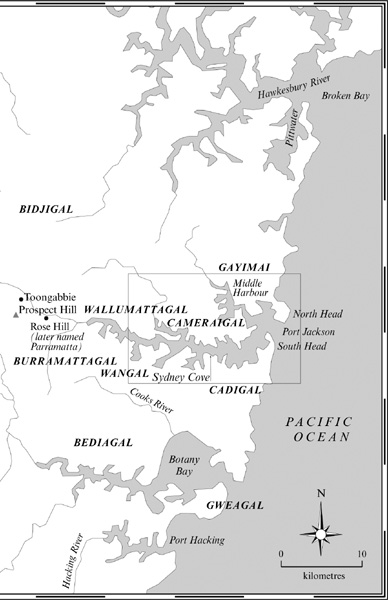

All Aboriginal personal and place-names have variations with which generally I have avoided burdening the text, though some of the variant spellings can be found in the notes.

As the text makes frequent use of imperial measurement, a conversion table to metric has been provided at the end of the book.

T.K.

one

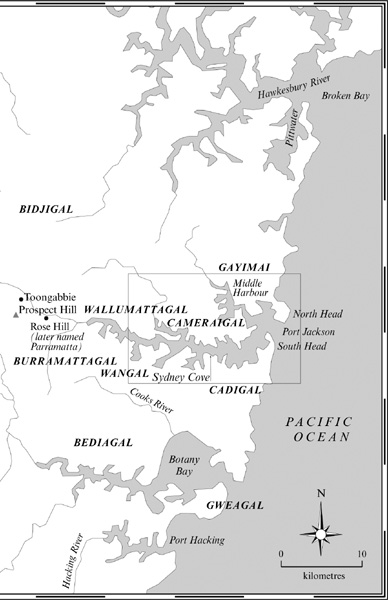

I F, IN THE NEW YEAR of 1788, the eye of God had strayed from the main games of Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa, and idled over the huge vacancy of sea to the south-east of Africa, it would have been surprised in this empty zone to see not one, but all of eleven ships being driven east on the screaming band of westerlies. This was many times more than the number that had ever been seen here, in a sea so huge and vacant that in today's conventional atlases no one map represents it. The people on the eleven ships were lost to the world. They had celebrated their New Year at 44 degrees South latitude with hard salt beef and a few musty pancakes. Their passage was in waters turbulent with gales, roiling from an awful collision between melted ice from the Antarctic coast and warm currents from the Indian Ocean behind them, and the Pacific ahead. High and irregular seas broke over the decks continuously, knocking the cattle in their pens off their legs. The travellers knew they were past the rocks of sub-Antarctic Kerguelen Island and were reaching for the dangerous southern capes of Van Diemen's Land, which they intended to round on their way to their destination.

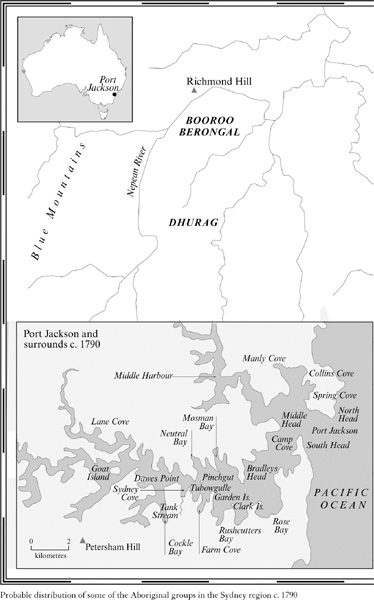

What would have intrigued the divine eye was the number of vesselsthough they travelled in two sections, each division separated from the other by a few hundred miles. So far in the history of Europe, only six ships had come into this area named the Southern Ocean, which lay between the uncharted south coast of New Holland (later to be known as Australia) and Antarctica's massive ice pack. In 1642, a Dutchman, Abel Tasman, a vigorous captain of the Dutch East India Company, had crossed this stretch to discover the island he would name Van Diemen's Land after his Viceroy in Batavia (now Jakarta), but which would in the end be named Tasmania to honour him.

His ships, a high-sterned, long-bowed yacht named Heemskerck and a round-sterned vessel of the variety called a flute, the Zeehaean, were of such minuscule tonnage as to be overshadowed by HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure's roughly 400 ton each. These last two, still tiny vessels by modern standards, less than one-third a football field in length, came through the Southern Ocean in 1774 under the overall command of the Yorkshireman James Cook. The Resolution travelled well to the south near the Antarctic ice mass, and rendezvoused with Adventure at the islands Tasman had named New Zealand. Then in 1776, the Resolution and the HMS Discovery, again under Cook, could have been seen in these waters. And that was all.

What were these eleven ships that in 1788 followed the path of Cook and Tasman to the southern capes of Van Diemen's Land? One might expect them to be full of Georgian conquistadors, or a task force of scientists to suit the enlightened age. If not that, then they must have carried robust dissenters from the political or religious establishment of their day.

The startling fact was they carried prisoners, and the guardians of prisoners. They were the degraded of Britain's overstretched penal system, and the obscure guardians of the degraded. Any concepts of commerce and science on these ships were secondary to the ordained penal purpose. Few aboard had commercial capacities, though a number of the gentlemen were part-time scientists. Their destination was to be not a home of the chosen, or even a chosen home, but a place imposed by authority and devised specifically with its remoteness in mind. The chief order of business for all of them, prisoners and guardians, was to apply themselves to a unique penal experiment.

The merchant ships of the fleet were to return to Britain after discharging their felons, picking up cargoes of cotton and tea in China and India on the return journey. But because this outward cargo was debased, some in Britain expected never to hear again from the fleet's passengers. It was believed they would become a cannibal kingdom on the coast they were bound for, andone way or anotherdevour each other.

THE IDEA OF EXPELLING CONVICTS to distant places was not new. It had occurred to European powers from the fifteenth century onwards, once they began acquiring huge and distant spaces in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. As a policy, it could solve many problems at the one time, including the problem which in modern days would be designated NIMBY, Not In My Backyard. But the chief difference of opinion soon emerged. As early as 1584, Hakluyt's Discourse for Western Planting proposed that sturdy vagabonds should be sent away to the colonies so that the fry of the wandering beggars of England that grow up idly and burden us to this realm may there be unladen, better bred up, and may people waste countries. Francis Bacon, however, debated the wisdom of unloading miscreants on far-off dominions in his essay Of Plantations. It is a shameful and unblessed thing, to take the scum of people, and wicked and condemned men, to be the people with whom you plant.

In reality, Hakluyt would win the debate with Bacon. It was the scum of people, and wicked and condemned menand womenwho made up the cargo of the criminal transports found in the Southern Ocean in the New Year of 1788. It would not have consoled the condemned on those wind-tossed mornings as they stirred and complained in their 18 inches of space on the convict decks that, uniquely placed as they were, they were also part of a long European tradition of transporting the unfortunate and the fallen, beginning with Cromwell's transportation of many Irish peasants, sent as labour to the plantations of the West Indies, and progressing to the 1656 order of the Council of State that lewd and dangerous persons should be hunted down for transporting them to the English plantations in America.

Next page