Americas Deadliest Hurricanes: The History of the Three Worst Hurricanes in American History

By Charles River Editors

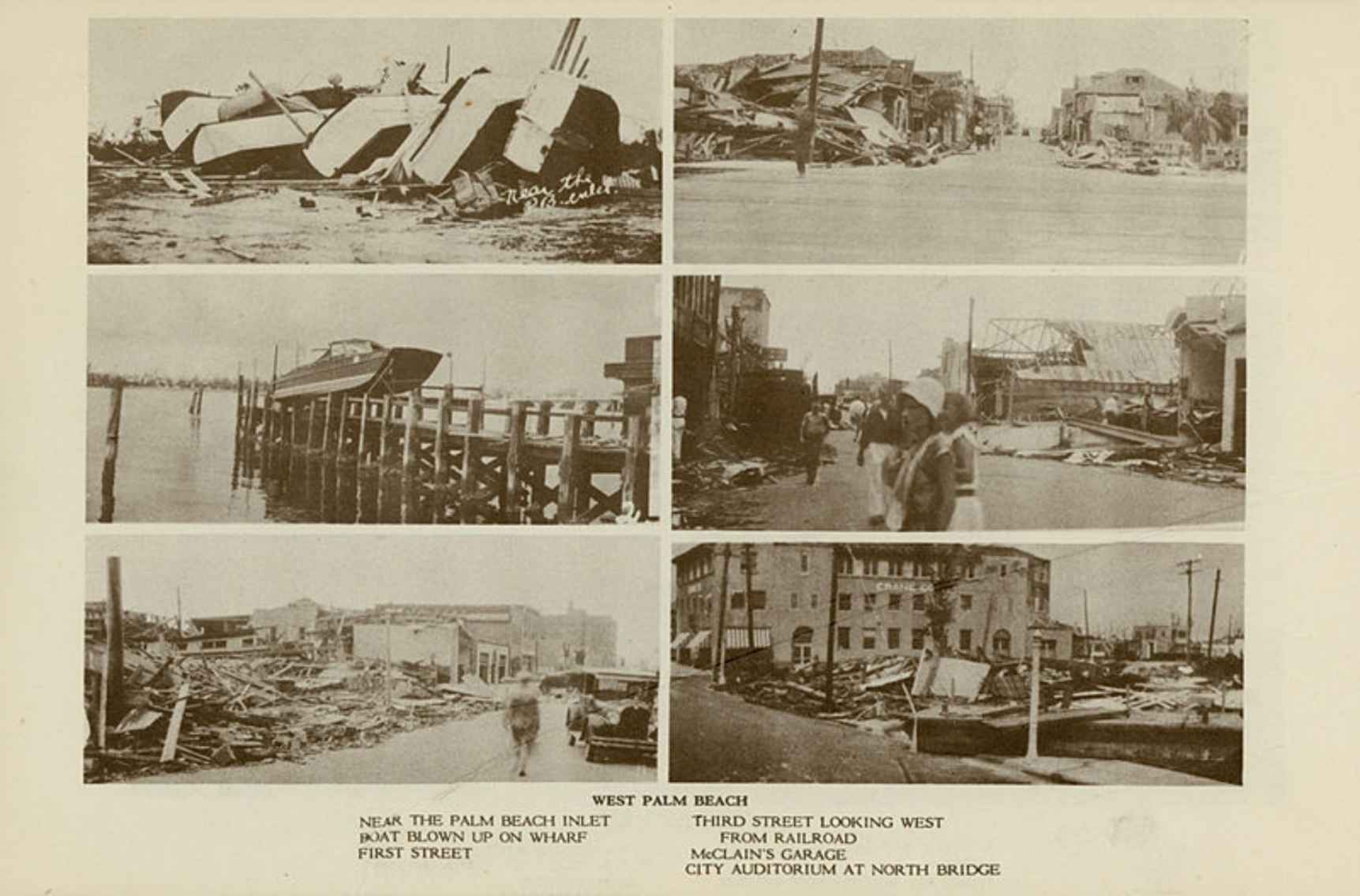

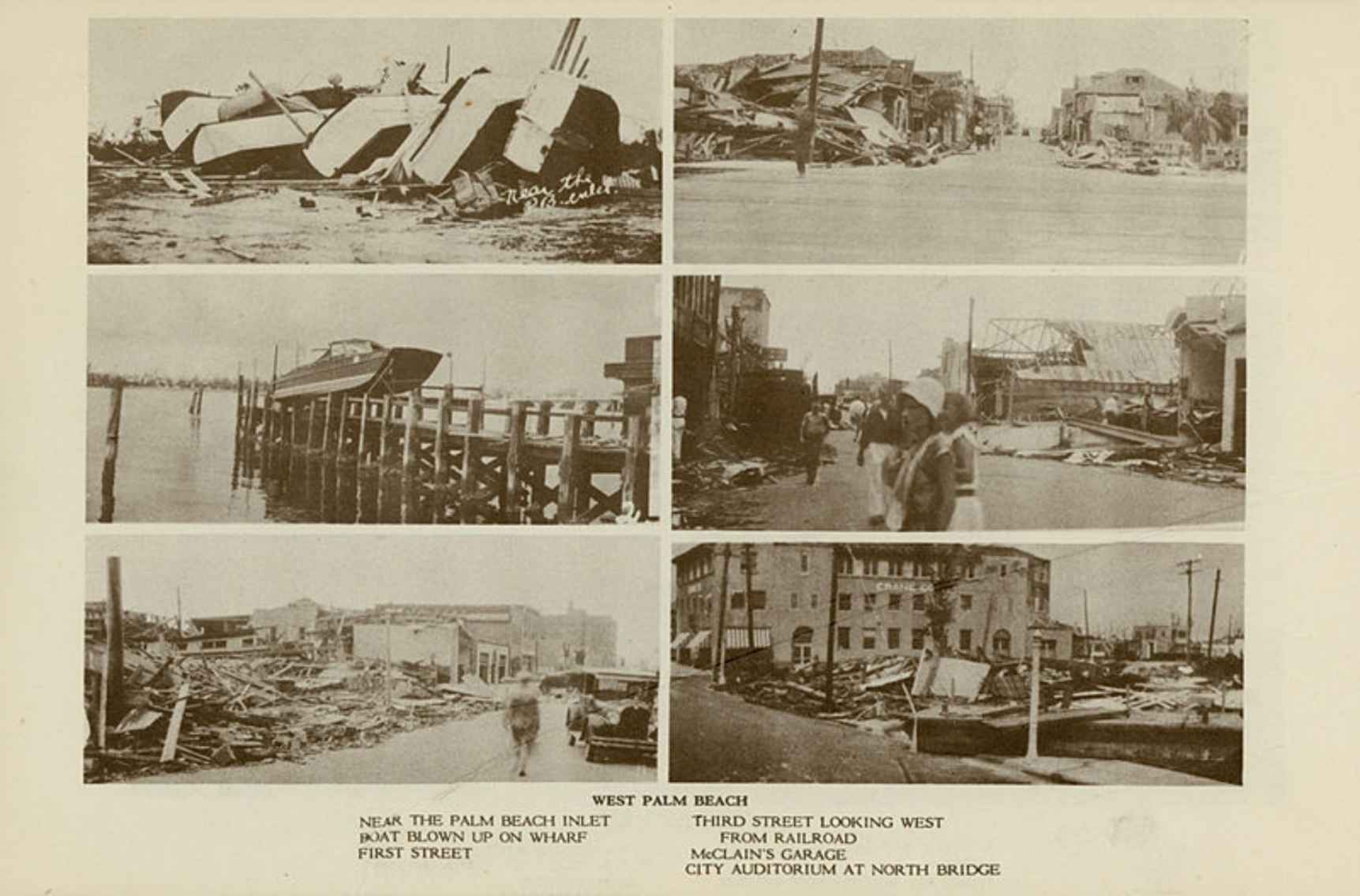

Pictures of damage done by the Lake Okeechobee Hurricane

About Charles River Editors

Charles River Editors is a boutique digital publishing company, specializing in bringing history back to life with educational and engaging books on a wide range of topics. Keep up to date with our new and free offerings with this 5 second sign up on our weekly mailing list , and visit Our Kindle Author Page to see other recently published Kindle titles.

We make these books for you and always want to know our readers opinions, so we encourage you to leave reviews and look forward to publishing new and exciting titles each week.

Introduction

Americas Deadliest Hurricanes

Picture of a 2x4 board driven through a palm tree in Puerto Rico by the 1928 Lake Okeechobee Hurricane

"Pointe a Pitre was a perfect picture of a city that had been dynamited during the preceding night." - William H. Hunt, American Consul on the Guadeloupe, in a letter to Secretary of State Frank Kellogg

Hurricanes have been devastating communities for thousands of years, bringing about various combinations of rain and wind that can do everything from taking down some dead limbs to wiping out houses. They are also common enough that people who live for any length of time in a region prone to having hurricanes are inclined to accept them as something of a periodic nuisance rather than a serious danger. Modern construction styles allow houses to withstand winds in excess of 100 miles an hour, and early warning systems allow people to evacuate. Thus, most hurricanes of the 21st century take fewer lives than a serious highway accident.

As a result, the world watched in horror as Hurricane Katrina decimated New Orleans in August 2005, and the calamity seemed all the worse because many felt that technology had advanced far enough to prevent such tragedies, whether through advanced warning or engineering. Spawning off the Bahamian coast that month, Katrina quickly grew to be one of the deadliest natural disasters in American history, killing more than 1,800 people and flooding a heavy majority of one of Americas most famous cities. At first, the storm seemed to be harmless, scooting across the Floridian coast as a barely noticeable Category 1 storm, but when Katrina reached the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico, its winds grew exponentially before slamming into the southern Louisiana coast as a massive Category 5 hurricane.

In addition to the deadly nature of the hurricane, it was also incredibly destructive as a result of failed levees around the New Orleans area. By the time the storm had passed, it had wreaked an estimated $108 billion of damage across the region, and the human suffering, with nearly 2,000 deaths and a million people displaced, was available for viewing across the world. Naturally, the reactions of political leaders would be heavily scrutinized in the aftermath, and people studied the lessons to be learned from the disaster to prevent a similar occurrence in the future.

As bad as Hurricane Katrina was, the hurricane that struck Galveston, Texas on September 8, 1900 killed several times more people, with an estimated death toll between 6,000-12,000 people. Prior to advanced communications, few people knew about impending hurricanes except those closest to the site, and in the days before television, or even radio, catastrophic descriptions were merely recorded on paper, limiting an understanding of the immediate impact. Stories could be published after the water receded and the dead were buried, but by then, the immediate shock had worn off and all that remained were the memories of the survivors. Thus, it was inevitable that the Category 4 hurricane wrought almost inconceivable destruction as it made landfall in Texas with winds at 145 miles per hour.

It was only well into the 20 th century that meteorologists began to name storms as a way of distinguishing which storm out of several they were referencing, and it seems somewhat fitting that the hurricane that traumatized Galveston was nameless. Due to the lack of technology and warning, many of the people it killed were never identified, and the nameless corpses were eventually burned in piles of bodies that could not be interred due to the soggy soil. Others were simply buried at sea. The second deadliest hurricane in American history claimed 2,500 lives, so its altogether possible that the Galveston hurricane killed over 4 times more than the next deadliest in the U.S. To this day, it remains the countrys deadliest natural disaster.

Similarly, the hurricane that struck southern Florida in September 1928 killed hundreds more, with an estimated death toll of over 2,500 people. Without the warnings available today, it was inevitable that the Category 5 hurricane wrought almost inconceivable destruction as it made landfall in Florida with winds at nearly 150 miles per hour. In addition to the powerful storm itself, the flooding of Lake Okeechobee, the 7 th largest freshwater lake in the country, exacerbated the damage by spilling across several hundred square miles, which were covered in up to 20 feet of water in some places.

Americas Deadliest Hurricanes: The History of the Three Worst Hurricanes in American History examines each of the deadly storms, from their meteorological origins to the tolls and aftermath of each one. Along with pictures of important people, places, and events, you will learn about the hurricanes like never before.

The Galveston Hurricane of 1900

1900

You know the year of 1900, children, many years ago

Death came howling off the ocean; death calls, you got to go.

Now Galveston had no seawall to keep the water down, and the

High tide from the ocean spread the water over the town. Wasnt That A Mighty Storm

In 1900, America was in the process of turning itself into a world power. The bold and brash Teddy Roosevelt was in the White House, the Wild West had just about been completely settled, and the immigrants who had come to the country during the great migration of the 1880s were now citizens and becoming increasingly upwardly mobile. Literacy was increasing, and joblessness was decreasing. In many ways, it was a golden age, and Galveston was a golden town, the home of so many newly prospering immigrants that it was sometimes called the Ellis Island of the West. It had survived the Civil War largely unscathed and was, in many ways, the jewel of Texas, with a largely middle-class population and an ever-expanding tax base.

In his report filed with the National Weather Service following the storm, meteorologist Isaac Cline described Galveston Island as a sand island about thirty miles in length and one and one-half to three miles in width. The course of the island is southwest to northeast, parallel with the southeast coast of the State. The City of Galveston is located on the east end of the island. To the northeast of Galveston is Bolivar Peninsula, a sand spit about twenty miles in length and varying in width from one-fourth of a mile to about three miles. Inside of Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula is Galveston Bay, a shallow body of water with an area of nearly five hundred square miles. The length of the bay along shore is about fifty miles and its greatest distance from the Gulf coast is about twenty-five miles. The greater portion of the bay lies due north of Galveston.