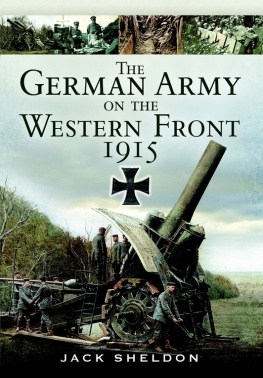

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Jack Sheldon 2007

9781783409044

The right of Jack Sheldon to be identified as the author of this work has

been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by

any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information

storage and retrieval system, without

permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Sabon by

Phoenix Typesetting, Auldgirth, Dumfriesshire

Printed and bound in England by

CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword

Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History,

Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Foreword

F or some ninety years now, Passchendaele the name widely given to the Third Battle of Ypres after that engagements murderous final phase has been collectively regarded by the British and Commonwealth public as a synonym for all the hardships and suffering borne by the front-line soldier in the First World War. This was particularly the case in the years following the publication of Lloyd Georges War Memoirs in the 1930s. In the unabridged version of his Memoirs , the former wartime Prime Minister predicted that the slaughter of Passchendaele, together with Verdun and the Somme, will always rank as the most gigantic, tenacious, grim, futile and bloody fights ever waged in the history of war. Defining Passchendaele as one of the wars greatest disasters, Lloyd George pronounced that no soldier of any intelligence would now defend this senseless campaign. As Ian M Brown has pointed out, Lloyd George, with the active assistance of Basil Liddell Hart, devoted over one hundred pages of his War Memoirs to Passchendaele as against twenty-seven to the battles of August to November 1918, when the Allies actually won the war. Lloyd Georges largely negative, and often venomous, views on the conduct of the battle by the British High Command were reinforced in the late 1950s by the appearance of Leon Wolffs In Flanders Fields , a book which heralded another round of Haig bashing, though Professor Brian Bond has wisely reminded us that Lloyd George, as Prime Minister at the time of Haigs 1917 Flanders offensive, had the constitutional responsibility to stop it if he deemed it to be failing or too costly in casualties. It is probably fair to say that, since the early 1970s, the Somme offensive of 1916 has supplanted Third Ypres as the battle which is popularly judged to have had the most significant impact, and to have inflicted the deepest physical and psychological scars, upon the British army and society as a whole. Nevertheless, Passchendaele has never lost its power to shock even the most hardened student of the Great War and, to many people, it remains the quintessential symbol of the horrors of the fighting on the Western Front.

In the last twenty years or so, there has been a steadily increasing flow of new books, essays, doctoral theses and battlefield guides covering virtually every aspect of the war from a British and Commonwealth standpoint, and especially the nature and conduct of the struggle on the Western Front. Historians such as Martin Middlebrook, Denis Winter, Bill Gammage, Desmond Morton, Tony Ashworth, Lyn Macdonald, Peter Liddle, Richard Holmes, Malcolm Brown, Nigel Steel and Peter Hart to name but a few have presented us with a highly detailed picture of the experiences and attitudes of British and Dominion junior officers and other ranks. Others including Tim Bowman, Terence Denman, James W Taylor, K W Mitchinson, Jill Knight and Helen McCartney and Mark Connelly have published important socio-military studies of various formations; Paddy Griffith, Bill Rawling, Martin Farndale and Jonathan Bailey are among those who have considerably enhanced our understanding of tactical developments and improvements in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF); numerous new unit histories have been produced; and thanks to the recent scholarship of Gary Sheffield, Ian Beckett, Andy Simpson, John Bourne, Simon Robbins, Chris Pugsley, Chris McCarthy, John Lee, and Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson we also have a much more precise idea of how operations were planned, and how command and control really functioned at different levels, in the BEF between 1914 and 1918. However, as Richard Holmes indicated in his Foreword to Jack Sheldons previous book, The German Army on the Somme 1914-1916 , we are distinctly less well catered for in terms of serious works, in English, on the German army in the First World War. As a result, our perception of the major operations on the Western Front, and of the lot of the ordinary soldier there, has inevitably become more than a trifle Anglocentric.

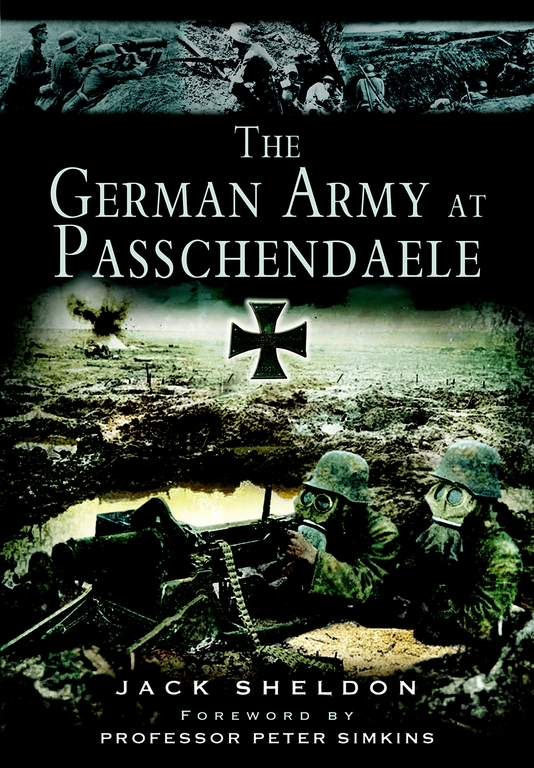

The same can be said of even the best recent works on Messines and Third Ypres. Apart from two short essays in the 1997 collection Passchendaele in Perspective , edited by Peter Liddle, most of the studies of these battles which have appeared since 1990 notably by Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, Nigel Steel and Peter Hart, Chris McCarthy, John Lee, Ian Passingham, Rob Thompson, Ian Beckett and Andrew Wiest have looked at the fighting in Flanders in 1917 primarily, if not exclusively, from the British side of the wire. While some useful and important works on the German army have also been published including studies by Timothy Lupfer, Bruce Gudmundsson, Dennis Showalter, Martin Samuels, John Lee, Martin Kitchen, Robert Asprey and Christopher Duffy they have focused mainly upon the German High Command and upon strategy and tactics rather than upon the daily, and nightly, ordeals of the Feldgrauen in their trenches, pillboxes and muddy shell-holes. With the distinguished exception of Christopher Duffy whose Through German Eyes: The British and the Somme 1916 was published in 2006 Jack Sheldon has, almost single-handed, begun to rectify this situation and to restore some sort of balance to the historiography of the First World War by furnishing us with a vivid and invaluable record of the men on the other side of No Mans Land, first in The German Army on the Somme and now in The German Army at Passchendaele . For this all serious students of the Great War are hugely in his debt.

So long as the German nation and the German army chose to maintain their occupation of large tracts of Belgium and northern France, the Allies, in their turn, had no realistic option other than to attack the Germans on the Western Front in an attempt to eject them, whatever the cost. To claim that, for the Allies, there was a viable alternative to the Western Front is to ignore or misunderstand the cardinal importance of logistics in the First World War. For the British it was just feasible to supply a massively-expanded BEF across the English Channel to France, where it could utilise the relatively sophisticated and extensive infrastructure of the French road, rail and waterways network. But, even on the Western Front, it was not until 1917-1918 that the BEF possessed an administrative and supply system which truly enabled it to begin to exploit the concurrent strides it was making in the spheres of operations and tactics. Bearing in mind the Royal Navys commitment to the blockade of Germany and to the absolutely vital task of anti-submarine warfare, it would surely have been well-nigh impossible to sustain a major army in a decisive land campaign through the mountainous Balkans or beyond Alexandretta and across the inhospitable Anatolian plateau, where communications were notoriously poor. If, then, the Germans had to be defeated on the Western Front, Jack Sheldons latest book - with its numerous accounts of resolute, heroic and skilful German defensive actions makes it abundantly clear that this would never be quickly or easily accomplished by the Allies. As Jack Sheldon underlines, moreover, the BEF was not the only army undergoing a process of learning and tactical improvement in 1917. Changes in German platoon organisation for example, as described in the extract from the history of Infantry Regiment 418, appear to have been based on the same principles as those adopted by the BEF early in 1917.