This book could not have been put together without the help of many, many people. Listing them all is probably impossible, but Ill give it a try.

Id like to thank some of the many people who helped me assemble the stories within. My dear friend Tom McIntyre not only made suggestions of books to excerpt, but also gave me a very insightful piece on what killing really means.

Lamar Underwood, the most voracious reader of outdoor literature that I know, made many valuable suggestions on what I might consider excerpting. While I was unable to obtain some of them, I was able to assemble many of Lamars recommended chapters.

Nick Lyons, with whom I had the great pleasure of working at the old Lyons Press, lent me many hard-to-find books from his library, with his thoughts on what might be appropriate for this book.

My friend, book author and screenwriter Terry Mort, was also instrumental in suggesting a number of excerpts for this book, including those by Anthony Trollope.

Laurie Morrow was helpful in getting permission for me to use the Corey Ford pieces, plus she helped track down and get some other, difficult-to-obtain excerpts.

Phil Caputo, Dave Petzal, Rick Bass, Tom McGuane, Bob Butz.... I thank all the authors whose names appear on the table of contents.

Amy Berkley, Field & Stream s photography editor, helped me find some crucial illustrations and photos for the book, some of them literally minutes before press time. Thank you Amy!

I also want to thank Steve Corcoran and Abigail Gehring of Skyhorse Publishing for all their hard work on this project. Without them, this book would never have come into existence.

Finally, I want to thank John Rice, who provided so many fine illustrations for this book.

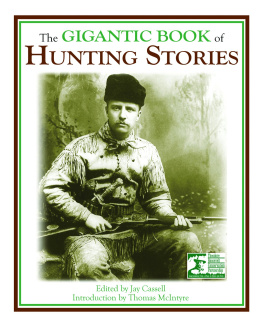

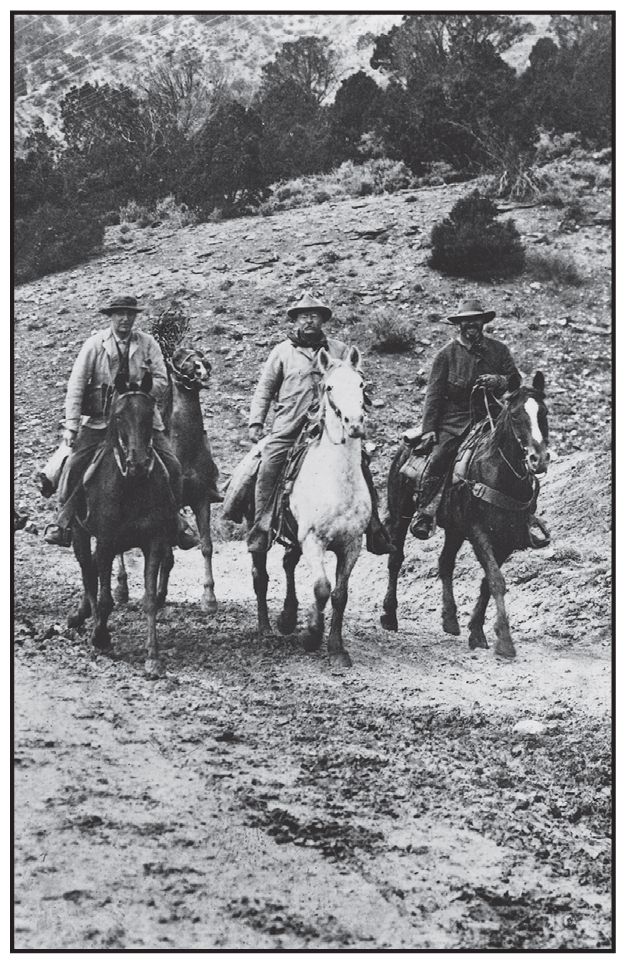

Theodore Roosevelt: Americas Greatest Hunter/Conservationist

JIM CASADA

Throughout his years, Theodore Roosevelt strove to live what he called the strenuous life. Following that credo, he was, at various times in his career, a soldier, diplomat, politician, author, reformer, and visionar ya true Renaissance man. Yet if one sought for bright, shining threads that ran through the fabric of his entire life, none would stand out more vividly than his love of hunting and his staunch commitment to conservation. The more one learns of his activities in these areas, the greater becomes ones appreciation of his zest for life and incredible accomplishments.

Born on October 27, 1858, in New York City, young Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., enjoyed many of the privileges associated with being the child of affluent parents, but from a tender age he also had firsthand acquaintance with adversity. A sickly, asthmatic lad, he faced health problems throughout his adolescent years. At an early age though, TR demonstrated the dogged perseverance that would characterize him as a hunter and in so many other arenas, saying simply: I ll make my body. Through boxing, wrestling, horseback riding, climbing, rowing, swimming, hiking, camping, and most of all, hunting, he did just that.

His father, although the owner of some lovely guns (such as a set of W. W. Greener percussion pistols and a Lefaucheux pinfire 12-gauge shotgun), had little interest in the outdoors. Instead, young Theodore found inspiration in the novels of Mayne Reid, books on exploration by the likes of Dr. David Livingstone, and in the accounts of African hunting by Roualeyn Gordon-Cumming and Sir Samuel Baker. His mentor for outdoor pursuits, at least at the outset, was his uncle, Robert Barnwell Roosevelt. A respected authority on fishing and ichthyology, he also wrote two hunting-related books, Game Birds of the Coasts and Florida and the Game Water Birds. As a long-time member of the New York Fish and Game Commission and some one who was quite active in politics, Uncle Robert probably had much more to do in shaping TRs philosophical outlook than did his father.

Another influential figure in shaping his perspectives and nurturing the budding outdoorsman was a Maine guide, outfitter, and lumberman, Bill Sewall. Even as Roosevelt was proving himself, as a collegian, an individual of great intellect possessing an exceptional work ethic (he earned a Phi Beta Kappa key at Har vard), he spent summers in the Maine wilderness. The first of these adventures came in 1878, following his fathers death late in the previous year. Its original intent was, likely, simple escape from the sorrow that threatened to consume the young man, but TRs linkage with Sewall proved to be a real watershed in his life.

Sewall initially saw him as a thin, pale youngster with bad eyes and a weak heart, and he fully expected three weeks of nursemaiding lay before him. Furthermore, by his own admission Roosevelt shot so poorly that he was moved to comment I am disgusted with myself. Yet the tenacity and sheer determination to succeed, no matter what the odds, which would become hallmarks of his career, served him well, and he insisted on arduous dawn-to-dusk activity every day. His confidence blossomed, as did his hardiness, and two subsequent Maine outings, both in 1879, added immensely to his education in the school of the outdoors.

Meanwhile, TR completed his undergraduate studies. With graduation a time for momentous decisions was at hand. Before considering thesegraduate study, a career path, possibly marriage, and other mattersRoosevelt took an extended hunting trip in company with his brother, Elliott. This type of escape to the wilderness and engagement in what he described as manly pursuits would become a prominent feature of his entire life. On this occasion and many subsequent ones, when faced by pressures in his personal or political life, TR would find that the solitude of the wild world, often shared with a close companion, was the ideal way to clear his mind and strengthen his resolve when critical decisions lay before him. During this particular trip, the brothers hunted upland birds and small game. TR treated himself to a new shotgun, and he got his first taste of the West, a region that would exert magnetic influence on him the rest of his life.

In his heart of hearts, he found that nothing held as much appeal for him as sport. Indeed, when writing of an 1883 trip on the Little Missouri River, he commented: I am fond of politics, but fonder still of a little big-game hunting. This was quite introspective as well as being a statement of simple reality. As Paul Cutright would note in the preface to his book, Theodore Roosevelt: The Naturalist (1956), Roosevelt began his life as a naturalist, and he ended it as a naturalist. Throughout a half century of strenuous activity his interest in wildlife, though subject to ebb and flow, was never abandoned at any time.

In the fall of 1883, bothered by a return of the asthma that had periodically plagued him throughout his youth and tired of the grind of politics (he had, after a brief stint as a graduate student at Columbia University, been elected to the State Assembly in New York), TR went on a hunting trip in the Dakota Badlands. He shot a buffalo and encountered various misadventures including miserable weather, proving along the way that he almost welcomed obstacles as a challenge. As TR suggested to his guide on the trip, Joe Ferris, It s dogged as does it. Ferris for his part, while initially harboring serious doubts about the hardihood of his client, in the end evaluated him as a plumb good sort.