First published in the UK as

The Mammoth Book of Endurance & Adventure

by Robinson, an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2000

Reprinted in the UK as Survivor: The Autobiography by Robinson, 2011

This edition published by Skyhorse, 2011

Copyright J. Lewis-Stempel, 2000 (unless otherwise stated)

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, New York 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, New York 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing Inc., a Delaware Corporation

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

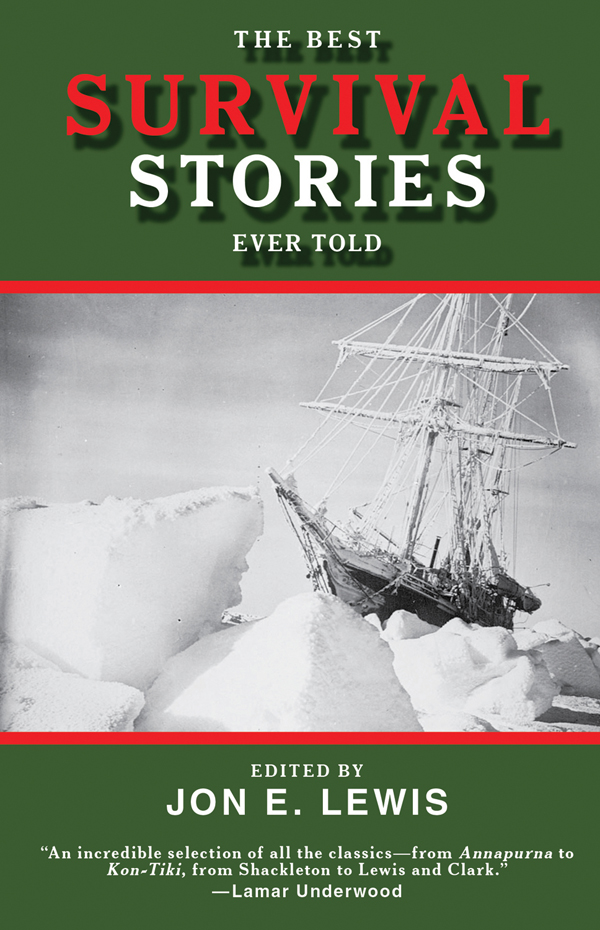

The best survival stories ever told/edited by Jon E. Lewis

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61608-455-4 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Explorers--Biography. 2. Adventure and adventurers--Biography. 3. Discoveries in geography. I. Lewis, Jon E., 1961

G200.S87 2011

910.92'2--dc23

2011018083

ISBN: 978-1-61608-455-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62087-665-7

Jon E. Lewis is a historian and writer, whose books on history and military history are sold worldwide. He is also editor of many The Mammoth Book of anthologies, including the bestselling On the Edge.

Jon holds graduate and postgraduate degrees in history, and his work has appeared in New Statesman, the Independent, Time Out and the Guardian. He lives in Herefordshire with his partner and children.

Praise for Jon E. Lewiss previous books:

A triumph.

Saul David, author of Victorias Army

This thoughtful compilation... [is] almost unbearably moving.

Guardian

Compelling Tornmys-eye view of war.

Daily Telegraph

What a book. Five stars.

Daily Express

ALSO AVAILABLE:

THE BEST COWBOY STORIES EVER TOLD

THE BEST FISHING STORIES EVER TOLD

THE BEST GHOST STORIES EVER TOLD

THE BEST HUNTING STORIES EVER TOLD

THE BEST PARANORMAL CRIME STORIES EVER TOLD

THE BEST PIRATE STORIES EVER TOLD

THE BEST SAILING STORIES EVER TOLD

THE BEST WAR STORIES EVER TOLD

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

... in memories we were rich. We had pierced the veneer of outside things. We had suffered, starved and triumphed, grovelled down yet grasped at glory, grown bigger in the bigness of the whole. We had seen God in his splendours, heard the text that nature renders. We had reached the naked soul of man.

Sir Ernest Shackleton

Mankind has always been an adventurer. No sooner was he out of his African cradle, than he was questing to see what lay over the next horizon, along the next bend of the river. And there has probably always been an audience for his tales. It is easy enough to conjure up a scene of Early Adventurer entertaining his tribal band around the campfire; certainly the earliest recorded exploration, that of Harkhuf to the land of Yam in around 2300 BC , dates back almost to the invention of writing itself.

Todays modern audience, however, is more clamorous for adventure than its predecessors. The reasons are not hard to find. In a world made cosy by a cornucopia of consumer conveniences, people are endlessly trapped in humdrum routines and a surfeit of safety. Few of us would protest against it but all of us know that we have lost sight of something: human mettle, spirit in adversity, the ability to live dangerously. Those who have dared go outside the confines of civilization to pit themselves against Nature remind us of what it is we are made of; their travails, to borrow the phrase of Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, enabling us to see the naked soul of man. They may thrill us, but more importantly they illuminate us. We need them to do what they do.

Shackleton reminds us that the adventurer has other fascinations. In cynical times with very few heroes, he retains an heroic cast. And few were more heroic than Shackleton. As an explorer he was a failure, as a hero he was everything. A true believer in duty and service, he escaped Antarctica and then went back to rescue those in his charge. The boss brought every man back safely. Its small wonder then that Shackleton is a curriculum item in business schools for those wanting to learn leadership skills.

By default, the majority of the eyewitness accounts collected in this book are by those who survived their personal tests of endurance, from Douglas Mawson struggling alone through an Antarctic blizzard to Charles Lindbergs fight against exhaustion aboard the Spirit of St Louis. They lived to bring home the tale. Sometimes, however, the records of the doomed have outlasted their authors, such as the harrowing last diaries found besides the corpse of R. F. Scott in Antarctica the great white laboratory of endurance and those of W. J. Wills in the desolate outback of Coopers Creek. These diaries, aside from chronicling hardship and perseverance almost beyond imagination, also give a salutary lesson: Nature is not easily beaten.

If the public needs its adventurers, there remains the thundering question of what motivates the adventurer. Over time, the necessities of food, shelter, uninhabited land, trade, warfare and imperial ambition have all whipped adventurers across the unknown. So too, the chance for the big prize, fame and glory (theres nothing new about the lust for celebrity). In the centuries following the Enlightenment, adventure has frequently been dressed as the pursuit of knowledge, with expeditions to the ends, heights and depths of the world tasked with some scientific or geographical purpose. And yet, as the following pages secretly testify, the real why? Stimulating the modern adventurer is the exploration of an entirely different objective the self in extremis. The proof of this is childishly easy, for almost all exploration in the last hundred years has, strictly speaking, been unnecessary, neither opening up new trade routes nor tracts of land to the touch of civilization. The relationship between audience and adventurer, then, is purely symbiotic: the public desires adventurers so that they can vicariously experience their own naked soul; fortuitously for the self-same public, some brave enough or maybe foolish enough men and women still feel a desire to test themselves to the limits.

It goes without saying that such a test should be a true endurance, one of mind and body. Endurance is usually conceived as sustained endeavour over time, but the meaning can be stretched to the maintenance of nerve and physical control over mere minutes of dangerous difficulty. Certainly, I have taken such licence in this book. Ekblaws sledge ride over wafer-thin ice, Nick Danzigers gun-running jeep journey over the Afghan border, Charles Watertons wrestle with a Guianese Cayman come to mind.

One of the necessary by-products of adventure is that it takes the adventurer and thus the reader to the last faraway places, where Nature still lives in unsullied magnificence (and deadly power). If this book is a chronicle of first-hand adventure, it is not least an anthology of white-knuckled travel writing. Sometimes, too, it is the travel writing of the highest art, such as Salomon Andres death-march diary across the Arctic, almost painterly in its depiction of the ice pack as a Magnificent Venetian landscape with canals between lofty hummock edges on both sides, water-square with ice-fountain and stairs down to the canals. Divine.