TALES OF

FRESH-WATER FISHING

FISHING BOOKS BY

ZANE GREY

TALES OF FISHES

TALES OF SOUTHERN RIVERS

TALES OF FRESHWATER FISHING

TALES OF FISHING VIRGIN SEAS

TALES OF SWORDFISH AND TUNA

TALES OF THE ANGLERS ELDORADO, NEW ZEALAND

ZANE GREY

PLATE I

Tales of

FRESHWATER

FISHING

ZANE GREY

THE DERRYDALE PRESS

Published in the United States of America

by The Derrydale Press

4720 Boston Way, Lanham, Maryland 20706

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK, INC.

Copyright 1928, 1955 by Zane Grey

First Derrydale paperback printing 2001

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any

means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Grey, Zane, 18721939.

Tales of Freshwater Fishing / Zane Grey.

p. cm.

Originally published: Tales of fresh-water fishing. New York ; London:

Harper & Brothers, 1928.

ISBN: 978-1-58667-052-8

1. Fishing I. Title

SH441 .G6 2001

799.11dc21 00-060140

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of

American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of

Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

TALES OF

FRESH-WATER FISHING

OUR summer outing at Lackawaxen slipped by swiftly, as only such days can, and the last one arrived. As we started out in the early morning the fog was rising from the river and hung like a great gray curtain along the mountain tops; while here and there, through rifts, the bright sun shone, making the dew sparkle on the leaves. Far up the mountain-side could be heard the loud caw of a crow and the shrill screech of a blue jay. A gray squirrel barked from his safe perch in a tree by the roadside. A ruffed grouse got up from the bushes along the road, and with a great whir disappeared among the trees. The air was keen, with a suspicion of frost in it, and fragrant with pine and hemlock. This was to be our last day. We were going to improve every moment of it, and, perhaps, add more glorious achievements to memorys store, to be lived over many times in the dark, cold days of winter. I looked at Reddy and marveled at the change a month could bring. He was the color of bronze and the spring of the deer-stalker was in his rapid step.

Well, looks as if you were not going to get that big one today, he said.

I am afraid not, I said. We would have had him if it had not been for your idiotic failure to land the big fellow you hooked the other day.

I wish you would stop reminding me of that and give me a chance to forget it, he answered. I suppose you never make any mistakes.

But it was so careless, I insisted, to have a four-pounder in your hands and then lose him.

Yes, I know; but lets forget it. I hope you will hook one twice as big and that he will break your tackle and give me a chance to get a picture of you for future reference, he replied.

At the lower end of the big eddy below Westcolang Falls, the Delaware narrows, and there commences a two-mile stretch of eddies, rifts, falls, and pools that would gladden the heart of any angler.

Now, my boy, I said, we will toss for choice as to who takes the other side going down.

I dont know if I would not just as willingly take this side, said Reddy, noting the swift water between him and the other shore.

No, I answered, that would not be fair. You know I am acquainted with the river, and the other side is the best, so here goes for the toss.

I won the toss and chose the near side, with a cheerful consciousness of my generosity, which was not in the least affected by Reddys suspicious glances. He was game, however, and waded into the swift water without another word; and he got safely across a deep place that had baffled me many a time. I stepped into the water, which was clear and beautiful, and as cold as ice. In a little eddy below me I saw the swirl of one of those vultures of the Delaware, a black bass, as he leaped for his prey and sent a shower of little shiners out of the water, looking like bright glints of silver as they jumped frantically for dear life. It was a grand day for fishing, and the bass seized hungrily at any kind of bait I offered. They were all small, however, and as I was after big game I returned them safe to the water.

Occasionally I looked over to see what Reddy was doing. Usually he was up to his neck in the water and half the time his rod was bent double. I also noticed something that worried me considerably. It was a long, black object, and it floated from a string tied to Reddys belt.

About noon we both made for the big stone near the middle of the river, where we rested and had our lunch. My fears were realized. That long black object was a three-pounder, a beautiful specimen of the red-eyed bronze-back of the Delaware.

Have you been fishing, or did you come along just for company? asked Reddy, cheerfully. I made some remark about the luck of certain people.

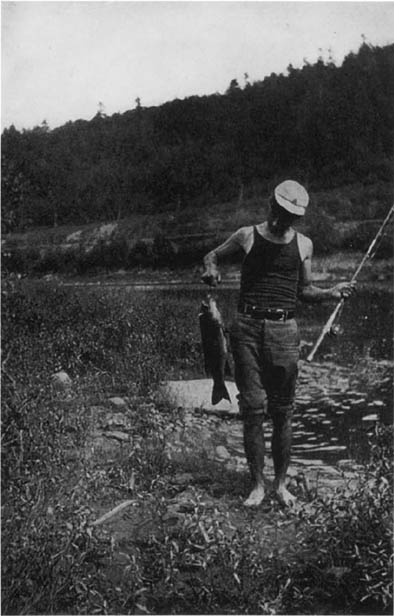

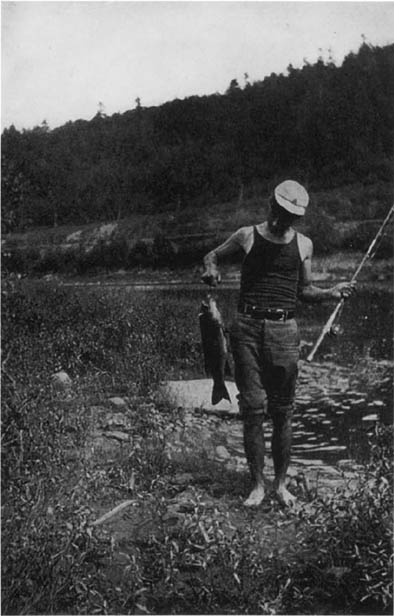

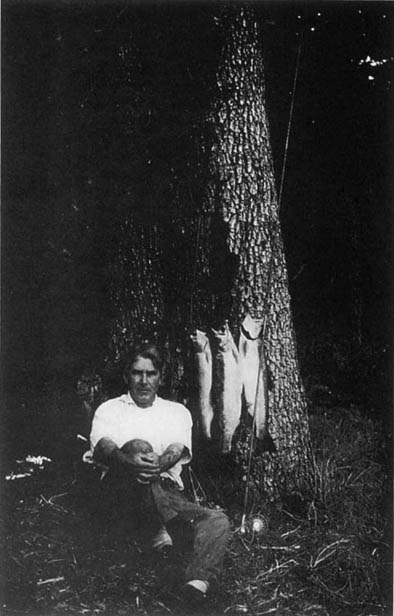

ZANE GREY WITH A SIX-POUND SMALL-MOUTH BLACK BASS OF THE DELAWARE

PLATE II

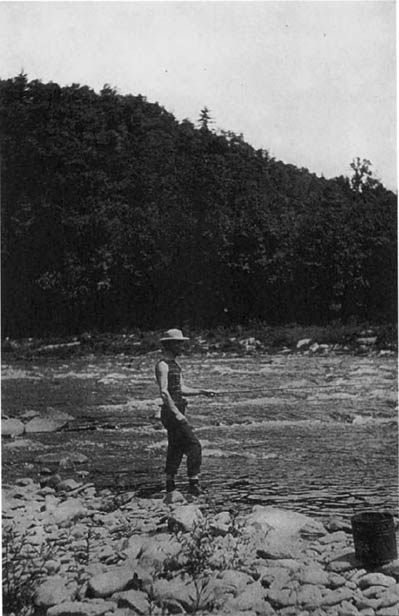

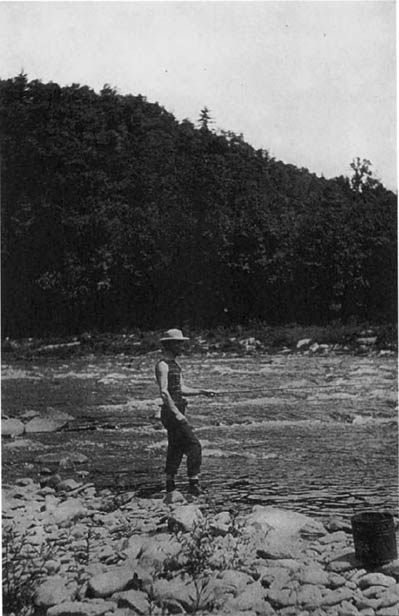

REDDY GREY CATCHING BAIT

PLATE III

Reddy was satisfied to stop then; in fact, he loafed the rest of the day, but I am a hard loser and I hated to quit. Five oclock found us at the foot of the rifts with only one more hole to fish. It was the Beer Mug, a hole so deep that it looks black, and always is covered with great patches of foam. It was a likely place for a big fellow, but I had never caught one there. Now I have memories of that hole which will never be effaced.

Reddy hooked and landed a big eel which wound the six-foot leader entirely around its slippery body. This made Reddy so tired that he said things which cannot be repeated here, and quit for the day.

I caught two small bass and a sunfish. Then I tried a hellgramite for a change. I fished the hole every way, but without success. I was reluctantly winding in my line, of which I had more than one hundred feet out, when I felt a little bite and hooked what I knew at once to be a chub. I continued to reel in my line in disgust, when suddenly it became fast on something. It felt like a water-soaked log. I pulled and pulled, but could not get the line off. I did not wish to lose fifty feet or more of good line, so I waded out and down the side of the pool to a point opposite where I thought I was fast. Imagine my surprise when I got there to find my line going slowly and steadily upstream, through water that was quite swift. I could not believe my eyes and was paralyzed for the moment. That chub was six inches long, probably, but he could never have moved the line in that manner. Reddy dropped his things and became interested in a moment, with his characteristic remark that something must be doing.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of