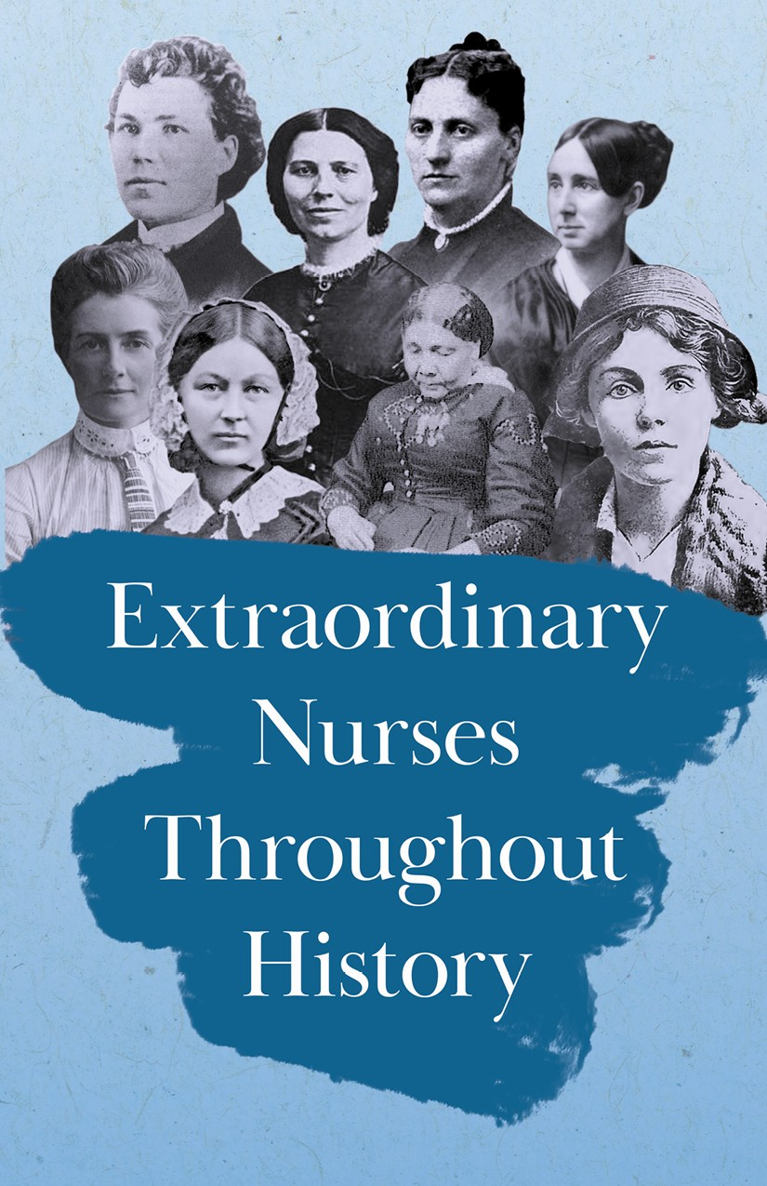

Extraordinary

Nurses

Throughout History

In Honour of

Florence Nightingale

By

VARIOUS

Copyright 2020 Brilliant Women

This edition is published by Brilliant Women,

an imprint of Read & Co.

This book is copyright and may not be reproduced or copied in any

way without the express permission of the publisher in writing.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

Read & Co. is part of Read Books Ltd.

For more information visit

www.readandcobooks.co.uk

"Lo! in that house of misery,

A lady with a lamp I see,

Pass through the glimmering gloom,

And flit from room to room."

Longfellow

Contents

FOREWORD

From time immemorial women have been content to be as those who serve. Non ministrari sed ministrarenot to be ministered unto but to ministeris not alone the motto of those who stand under the Wellesley banner, but of true women everywhere.

For centuries a woman's own home had not only first claim, but full claim, on her fostering care. Her interests and sympathiesher mother lovebelonged only to those of her own household. In the days when much of the labor of providing food and clothing was carried on under each roof-tree, her service was necessarily circumscribed by the home walls. Whether she was the lady of a baronial castle, or a hardy peasant who looked upon her work within doors as a rest from her heavier toil in the fields, the mother of the family was not only responsible for the care of her children and the prudent management of her housekeeping, but she had also entire charge of the manufacture of clothing, from the spinning of the flax or wool to the fashioning of the woven cloth into suitable garments.

Changed days have come, however, with changed ways. The development of science and invention, which has led to industrial progress and specialization, has radically changed the woman's world of the home. The industries once carried on there are now more efficiently handled in large factories and packing-houses. The care of the house itself is undertaken by specialists in cleaning and repairing.

Many women, whose energies would have been, under former conditions, inevitably monopolized by home-keeping duties, are to-day giving their strength and special gifts to social service. They are the true mothersnot only of their own little broodbut of the community and the world.

The service of the true woman is always "womanly." She gives something of the fostering care of the mother, whether it be as nurse, like Clara Barton; as teacher, like Mary Lyon and Alice Freeman Palmer; or as social helper, like Jane Addams. So it is that the service of these "heroines" is that which only women could have given to the world.

Many women who have never held children of their own in their arms have been mothers to many in their work. It was surely the mother heart of Frances E. Willard that made our "maiden crusader" a helper and healer, as well as a standard bearer. It was the mother heart of Alice C. Fletcher, that made that student of the past a champion of the Indians in their present-day problems and a true "campfire interpreter." It was the woman's tenderness that made Mary Slessor, that torch-bearer to Darkest Africa, the "white mother" of all the black people she taught and served.

The Russian peasants have a proverb: "Labor is the house that Love lives in." The women, who, as mothers of their own families, or of other children whose needs cry out for their understanding care, are always homemakers. And the work of each of theseher labor of loveis truly "a house that love lives in."

Mary R. Parkman

REPRESENTATIVE WOMEN

THE FREE NURSE

By Ingleby Scott

By the Free Nurse I mean to indicate the Sister of Charity who devotes herself to the sick for their own sake, and from a natural impulse of benevolence, without being bound by any vow or pledge, or having any regard to her own interests in connexion with her office.

There is no dispute about the beauty and excellence of the nursing institutions of the continent, Catholic and Protestant. There can be no doubt that many lives are utilised by them, which would otherwise be frittered away from want of pursuit and guidance. Every town where they live can tell what the blessing is of such a body of qualified nurses, ready to answer any call to the sick-bed. The gratitude of their patients, and the respect of the whole community, testify to their services and merits: and the frequent proposal of some experiment to naturalise such institutions in England, proves that we English are sensible of the beauty of such an organisation of charity. My present purpose, however, is to speak of a more distinctive kind of woman than those who are under vows. However sincere the compassion, however disinterested the devotedness, in an incorporated Sister of Charity, she lies under the disadvantage of her bonds in the first place, and her promised rewards in the other. She may now and then forget her bonds; and there are occasions when they may be a support and relief to her; but they keep her down to the level of an organisation which can never be of a high character while the duty to be performed is regarded as the purchase-money of future benefits to the doer. Those who desire to establish the highest order of nursing had rather see a spontaneous nurse weeping over the body of a suffering child that has gone to its rest than a vowed Sister wiping away the death-damps and closing the eyes, under the promise of a certain amount of remission of sins in consequence. There is abundance of room in society for both vowed and spontaneous nurses, in almost any number; but, their quality as nurses being equal, the strongest interest and affection will always follow the freer, more natural, and more certainly disinterested service. The weaker sort are perhaps wise to put themselves under the orders of authority, which will settle their duty for them: but such cannot be representative women, except by some force of character which in so far raises them above the region of authority. The Representative Women among Nurses are those who have done the duty under some natural incitement, of their own free will, and in their own way.

It will not be supposed, for a moment, that I am speaking slightingly of such organisation as is necessary for the orderly and complete fulfilment of the nursing function. In every hospital where nurses enter freely, and can leave at pleasure, there must be strict rules, settled methods, and a complete organisation of the body of nurses, or all will go into confusion. The authority I refer to as a lower sanction than personal free disposition, is that of religious superiors, who impose the task of nursing as a part of the exercises by which future rewards are to be purchased. There cannot be a more emphatic pleader for hospital and domestic organisation, as a means to the best care of the sick, than Florence Nightingale: and at the same time, all the world knows that she would expect better things from women who become nurses of their own accord, and remain so, through all pains and penalties, when they might give it up at any hour, than from nuns who enter that path of life because it leads (as they believe) straightest to heaven, and do every act at the bidding of a conscience-keeper who holds the ultimate rewards in his hand.