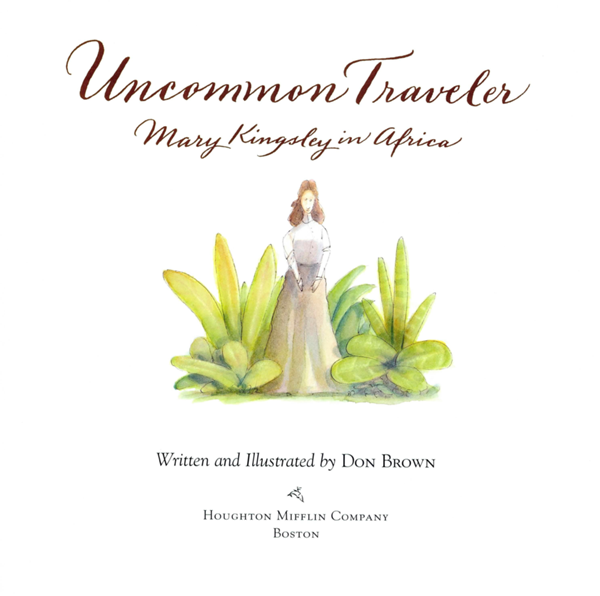

Uncommon Traveler

Mary Kingsley in Africa

Written and Illustrated by D ON B ROWN

H OUGHTON M IFFLIN C OMPANY

B OSTON

Copyright 2000 by Don Brown

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com

Calligraphy by Deborah Nadel.

The text of this book is set in Goudy.

The illustrations are pen and ink and watercolor on paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brown, Don, 1949

Uncommon traveler: Mary Kingsley in Africa / written and illustrated by Don Brown. p. cm.

Summary: A brief biography of the self-educated nineteenth-century English woman who, after a

secluded childhood and youth, traveled alone through unexplored West Africa in 1893 and 1894

and learned much about the area and its inhabitants.

RNF ISBN 0-618-00273-1 PAP ISBN 0-618-36916-3

1. Kingsley, Mary Henrietta, 1862-1900Juvenile literature. 2. ExplorersAfrica, West

BiographyJuvenile literature. 3. ExplorersGreat BritainBiographyJuvenile literature.

4. Woman explorersAfrica, WestBiographyJuvenile literature. 5. Women explorers

Great BritainBiographyJuvenile literature. 6. Africa, WestDiscovery and exploration

BritishJuvenile literature. [1. Kingsley, Mary Henrietta, 18621900. 2. Explorers.

3. WomenBiography. 4. Africa, WestDiscovery and exploration.] I. Title.

DT476.23.K56B76 2000

916.604'312'092dc21

[B]

99-087823

Manufactured in China

LEO 10 9 8

For Tyler, an uncommon brother

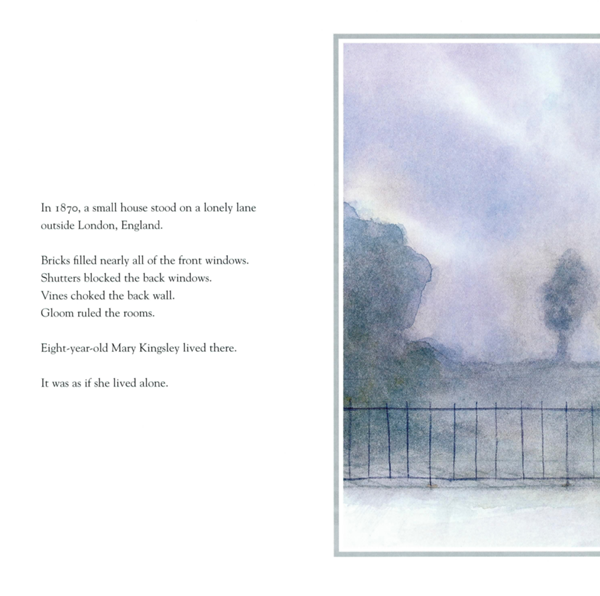

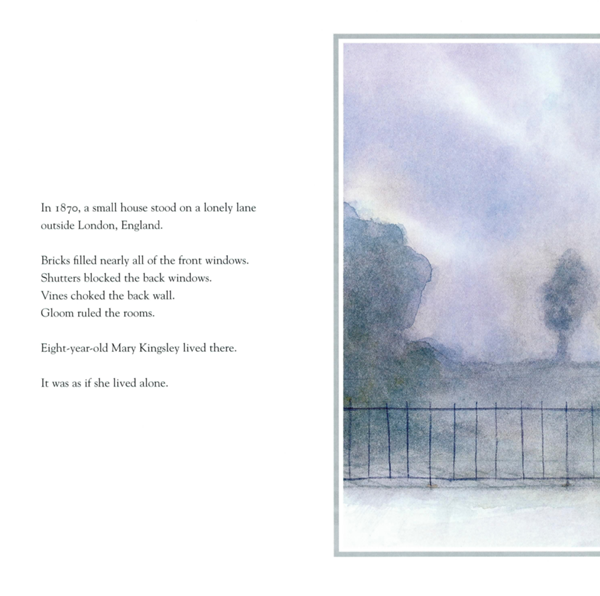

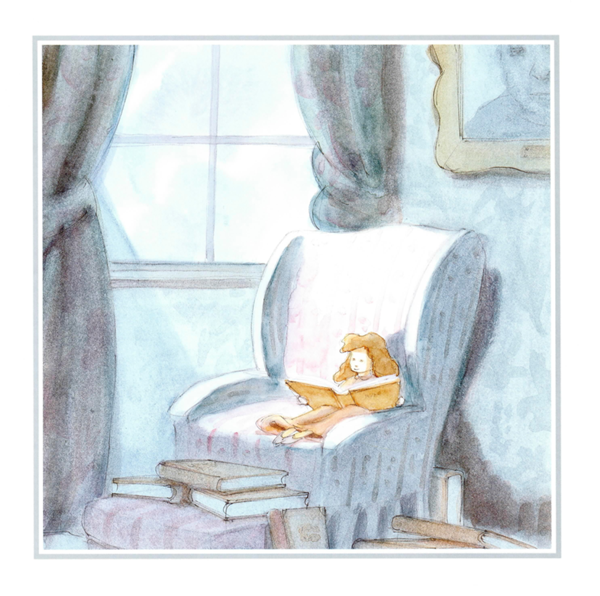

In 1870, a small house stood on a lonely lane outside London, England.

Bricks filled nearly all of the front windows. Shutters blocked the back windows. Vines choked the back wall. Gloom ruled the rooms.

Eight-year-old Mary Kingsley lived there.

It was as if she lived alone.

Her father, George, traveled the world seeking adventure.

Her mother, also named Mary, was sickly and rarely left her bed.

Her younger brother, Charles, was away at school.

Mary didn't go to school and would never go to school.

"The whole of my childhood and youth was spent at home in the house and garden," she later said. "The living outside world I saw little of. I felt out of place at the few parties I ever had the chance of going to, for I knew nothing of play and such things."

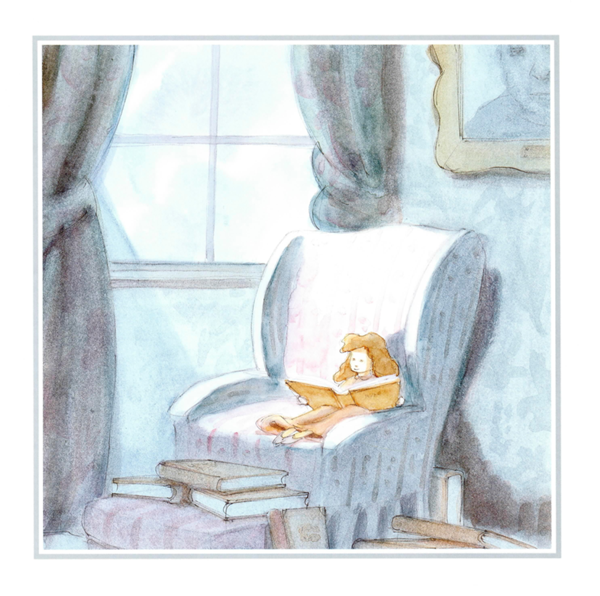

Still, Mary was happy.

"I had a great, amusing world of my own: the books in Father's library."

Novels and poetry books.

Science and history books.

Travel and adventure books.

Books were her companions and teachers.

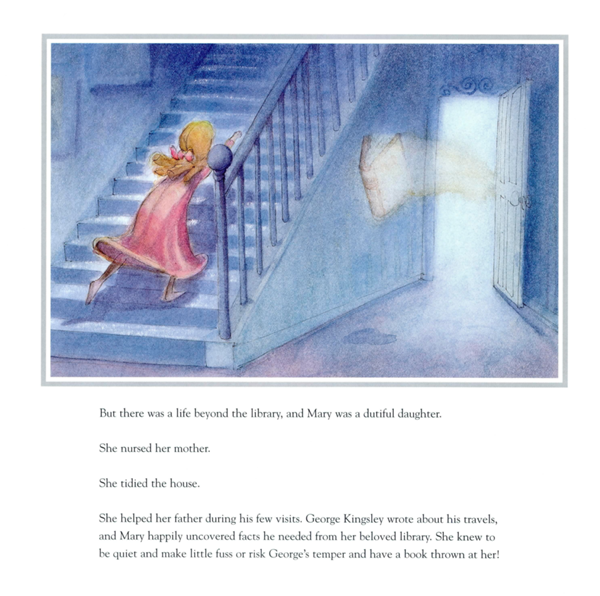

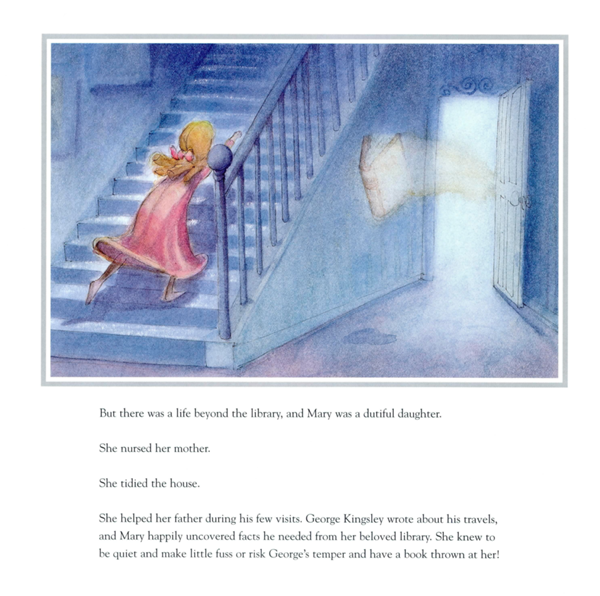

But there was a life beyond the library, and Mary was a dutiful daughter.

She nursed her mother.

She tidied the house.

She helped her father during his few visits. George Kingsley wrote about his travels, and Mary happily uncovered facts he needed from her beloved library. She knew to be quiet and make little fuss or risk George's temper and have a book thrown at her!

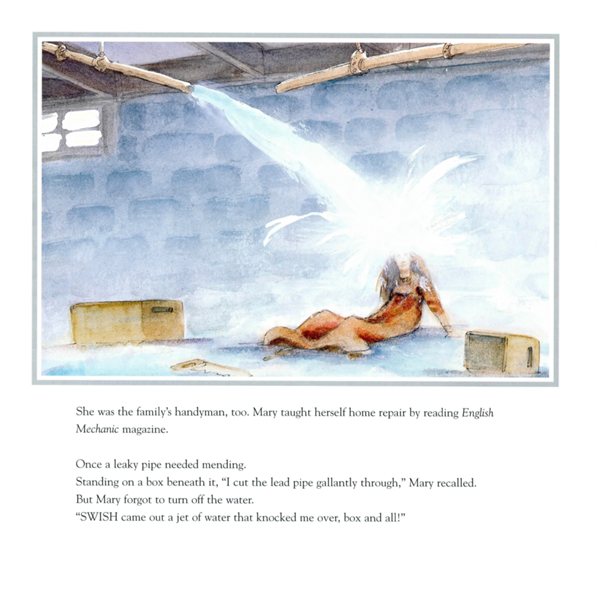

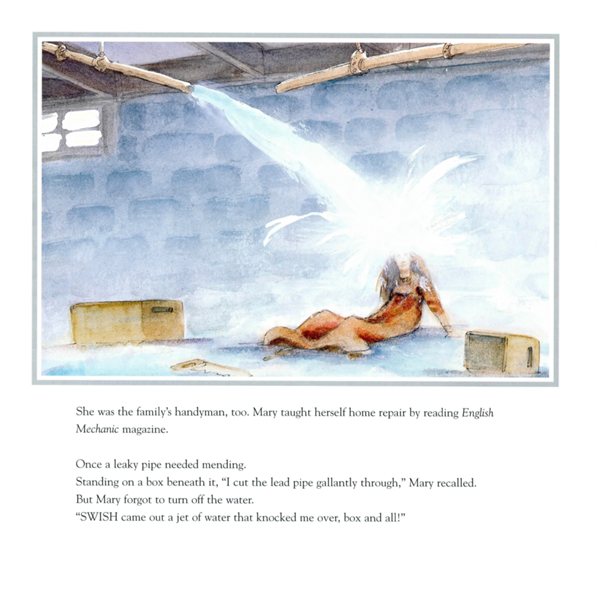

She was the family's handyman, too. Mary taught herself home repair by reading English Mechanic magazine.

Once a leaky pipe needed mending.

Standing on a box beneath it, "I cut the lead pipe gallantly through," Mary recalled.

But Mary forgot to turn off the water.

"SWISH came out a jet of water that knocked me over, box and all!"

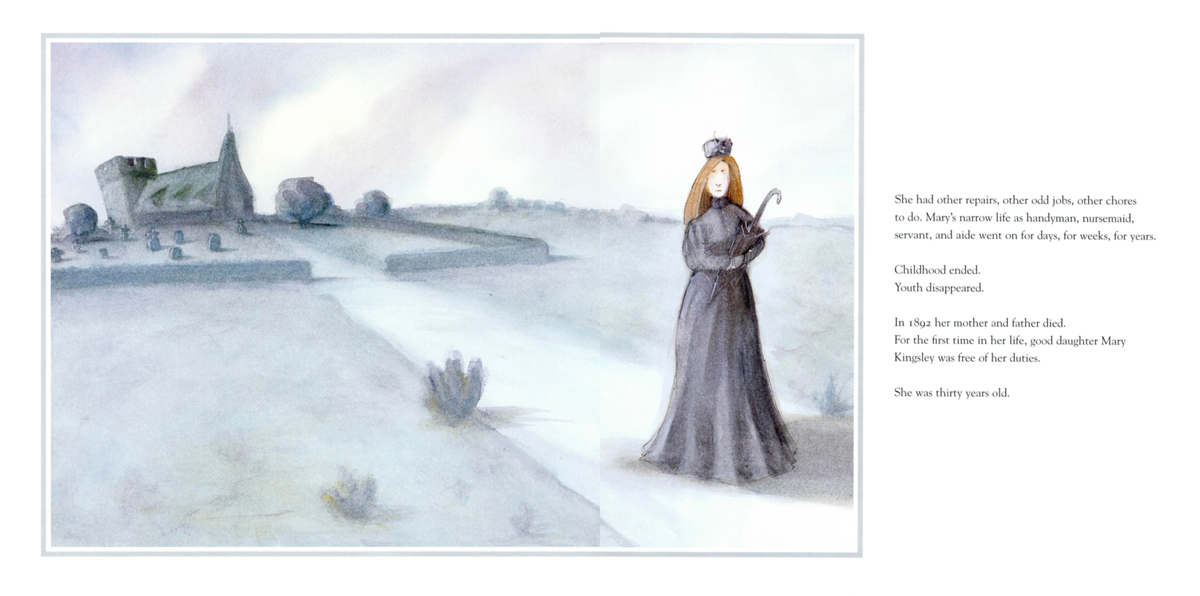

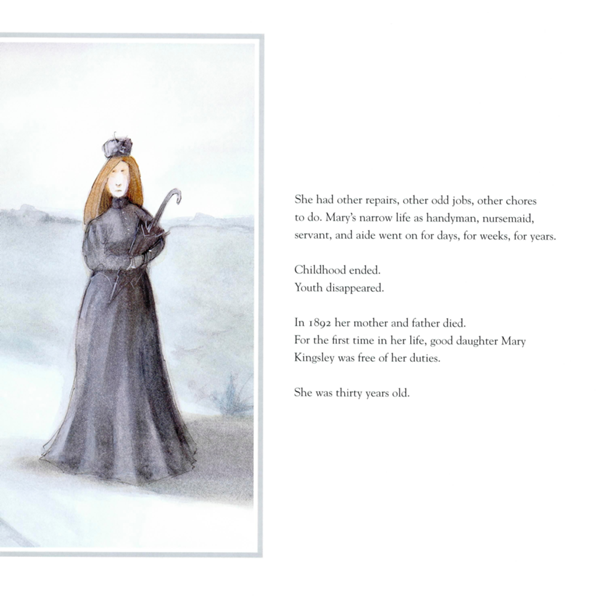

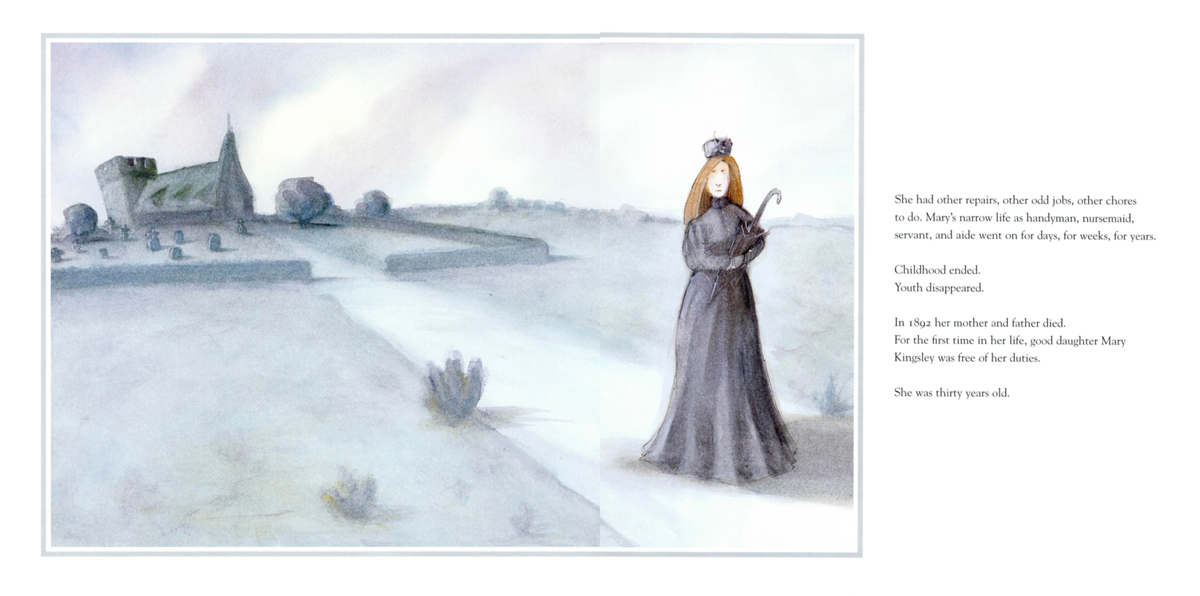

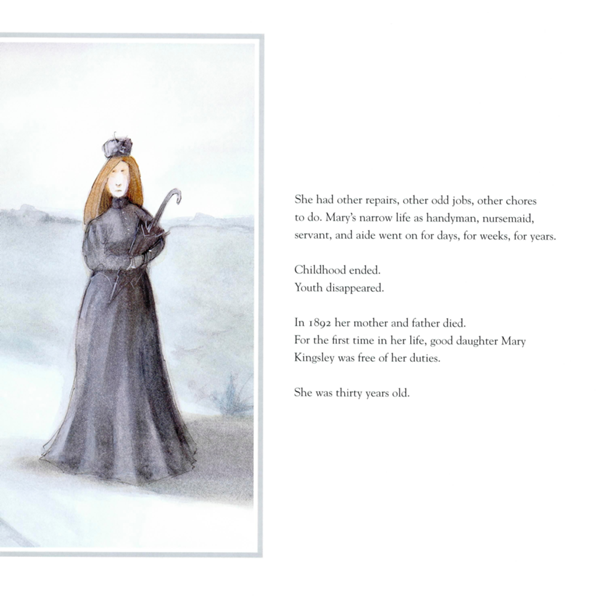

She had other repairs, other odd jobs, other chores to do. Mary's narrow life as handyman, nursemaid, servant, and aide went on for days, for weeks, for years.

Childhood ended.

Youth disappeared.

In 1892 her mother and father died.

For the first time in her life, good daughter Mary

Kingsley was free of her duties.

She was thirty years old.

Her world, once cramped and dark, was now as big as the globe. The idea of it made her head spin.

Inspired by her father's journeys and the travel books she loved, Mary had the remarkable notion of going to West Africa.

People thought Mary was foolish. Much of West Africa was a mystery, even to those who lived there. Visitors risked disease, wild animal attacks, and the hostility of some Africans. West Africa was not a place for a single woman to visit.

Mary ignored the warnings and planned her trip. She would travel light, without a tent, eating native food and wearing her regular English clothes. She would trudge, wade, clamber, and climb in a high-necked, long-sleeved shirt, long heavy skirt, and proper Victorian boots.

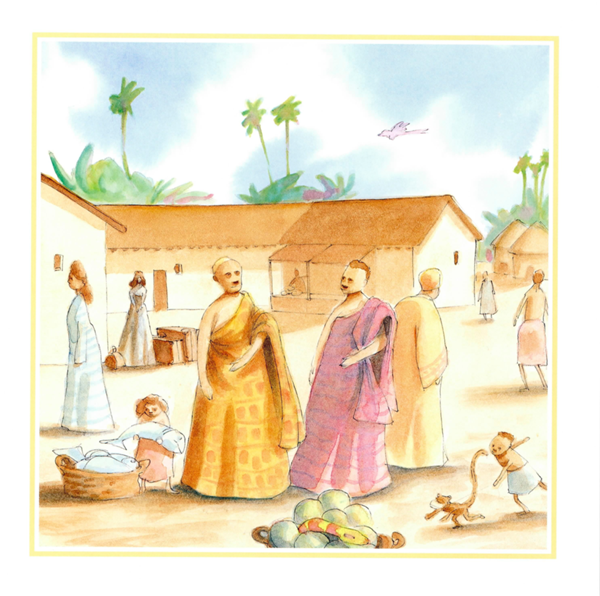

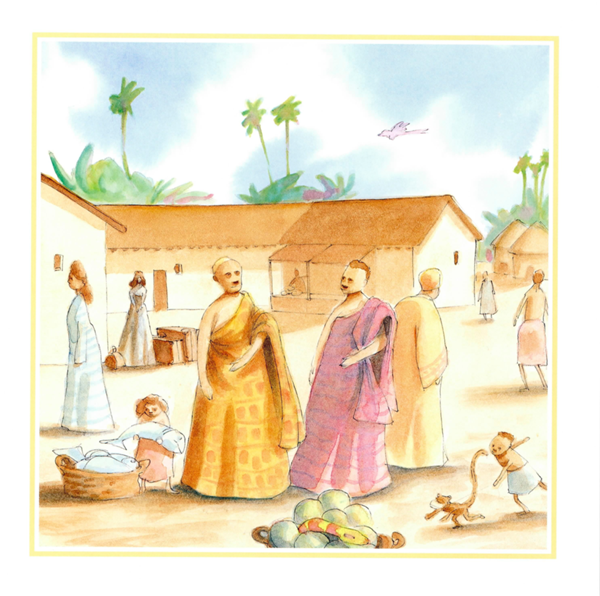

She arrived in West Africa in 1893. Mary was delighted. Oh, the grand and vivid sights, sounds, and smells she met!

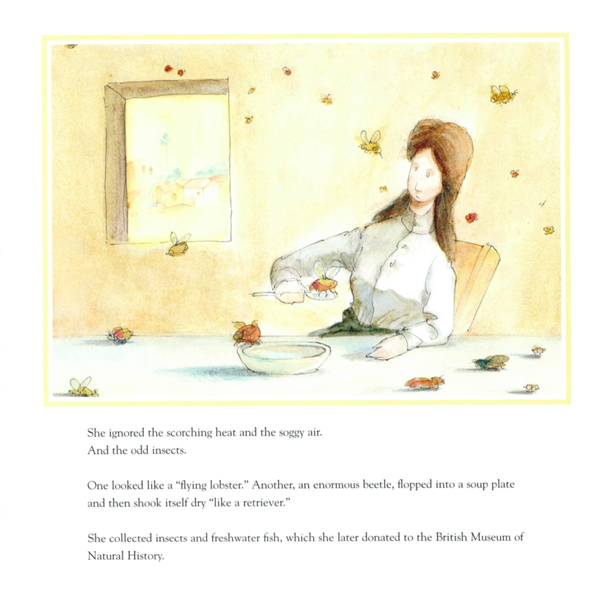

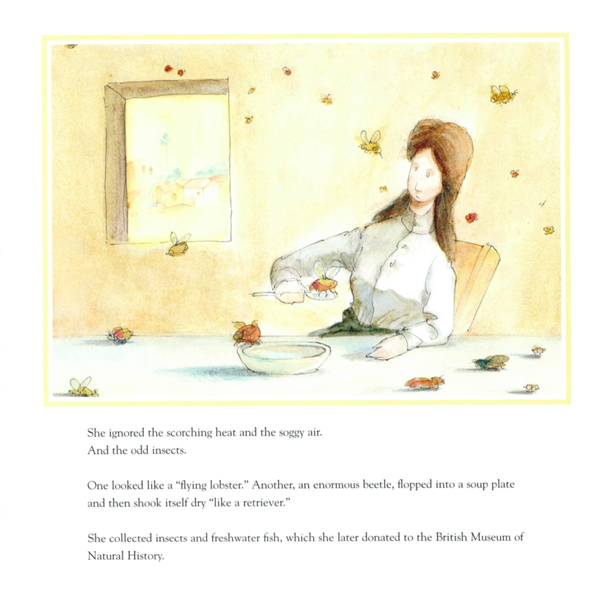

She ignored the scorching heat and the soggy air.

And the odd insects.

One looked like a "flying lobster." Another, an enormous beetle, flopped into a soup plate and then shook itself dry "like a retriever."

She collected insects and freshwater fish, which she later donated to the British Museum of Natural History.

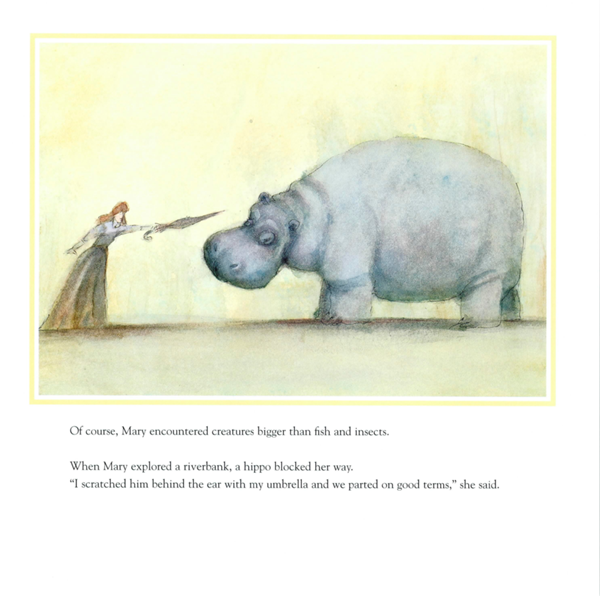

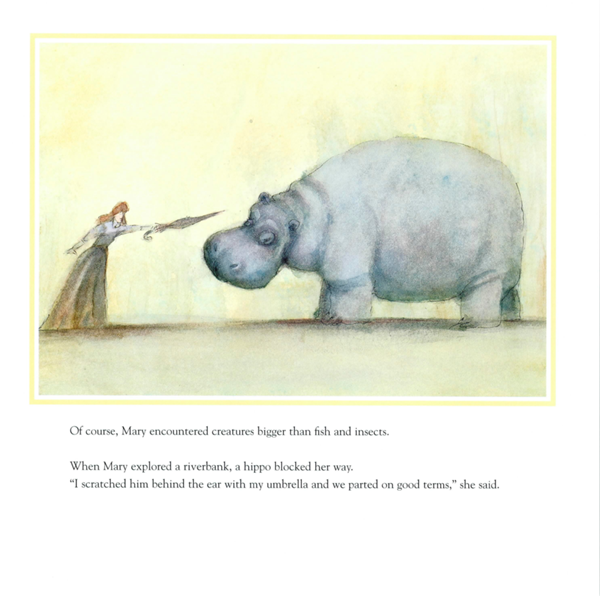

Of course, Mary encountered creatures bigger than fish and insects.

Next page