Table of Contents

PENGUIN CLASSICS

CLASSICS EARLY WRITINGS

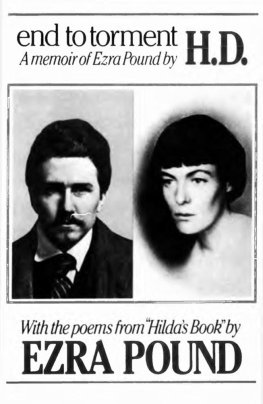

EZRA POUND, poet, essayist, editor, translator, anthologist and literary provocateur, was one of the major modernists of the twentieth century. Born in Hailey, Idaho, on October 30, 1885, he attended the University of Pennsylvania and Hamilton College, then briefly taught at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana, before heading to Europe in 1908 and settling for a time in Venice, where he published his first book, A Lume Spento. He then moved to London, where he continued to write and met such authors as Yeats, Henry James, Wyndham Lewis, Ford Madox Ford, and T. S. Eliot. In late 1920 he and his wife, Dorothythey had married in 1914moved to Paris, but not before he guided movements like Imagism and Vorticism to prominence and aided writers like H.D. and Joyce in getting their early works published.

In Paris, Pound met the American violinist Olga Rudge, who would become his companion for almost fifty years, and continued to work on his long poem, The Cantos, which he had begun in 1917. He also edited Eliots The Waste Land and became friendly with Picabia, Brancusi, Duchamp, Cocteau, and Ernest Hemingway, while working on an opera, Le Testament, based on the work of Franois Villon. In 1923 he visited Rimini and became absorbed by the life of Sigismundo Malatesta and his Tempio, which would prompt the Malatesta Cantos, numbers VIII-XI of his long work. He continued to publish criticism and visit Italy, where he and Dorothy, and then Olga, moved in 1924, settling in Rapallo and Venice. At the same time, prose works like the ABC of Economics (1933) and Jefferson and/or Mussolini (1935), became increasingly economic and social in outlook.

Pound remained in Italy the rest of his life, except for two trips to the United States: the first, in 1939, was an aborted attempt to visit President Roosevelt and several congressmen to prevent U.S. involvement in World War II; the second, in 1945, occurred after his arrest for treason at the end of the war following his anti-American broadcasts on Italian radio. Declared to be mentally unfit to stand trial, Pound was committed to St. Elizabeths mental hospital in Washington, D.C., where he remained from 1946 to 1958, during which time he continued to write. In 1949, he won the prestigious Bollingen Prize for The Pisan Cantos, which he began while at a U.S. Army detention camp in Pisa, Italy. Following his release from St. Elizabeths, Pound returned to Italy, where he wrote sporadically. He died in Venice on November I, 1972.

IRA B. NADEL, educated at Rutgers and Cornell universities, is professor of English and Distinguished University Scholar at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. His books include Biography: Fiction, Fact and Form; Joyce and the Jews; Various Positions: A Life of Leonard Cohen; Double Act: A Life of Tom Stoppard; and Ezra Pound: A Literary Life. He has also edited The Letters of Ezra Pound to Alice Corbin Henderson and the Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound.

Introduction

T. S. Eliot called Ezra Pound il miglior fabbro, the better craftsman. James Joyce declared he was a miracle of ebulliency, gusto and help. W. B. Yeats recalled that to talk over a poem with him was like getting you to put a sentence into dialect. All becomes clear and natural. Wyndham Lewis summed him up as the demon pantechnicon driver, busy with removal of the old world into new quarters. The supercharged Ezra Pound seemed to be everywhere at once in the literary world of the early twentieth century, cajoling, hectoring, provoking, and refashioning literature whether in London, Paris, New York, or Rapallo. He met Henry James and corresponded with Hardy. He redirected the poetry of Yeats, discovered Robert Frost, and promoted H.D. His admirers were right: Pound was the quintessential modernist, the figure who overturned poetic meter, literary style, and the state of the long poem. Only his experimentation with new forms and determination to make it new exceeded his boldness in editing The Waste Land, overseeing publication of Ulysses, and creating new movements like Imagism. As he wrote in a note to his early poem Histrion, I do not teachI awake.

Pounds multiple importance might be condensed to a single conviction: poetry shapes the world. Like Shelley, who believed that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world, Pound knew that poetry informed the moral and aesthetic values of a culture: Poetry is a sort of inspired mathematics which gives us equations ... for the human soul, he proclaimed. Literature, he announced in the ABC of Reading, is news that stays news because it galvanizes readersespecially if it follows his precept to use no superfluous word. Cut direct, he ordered when discussing style. Pound, in other words, was a literary activist who insisted that ideas be put into action.

Some of Pounds best and most challenging work is his earliest. Rewriting the dramatic monologue, the Provenal lyric, or the pentameter line meant the discovery of personae, Imagism, and a new form of dramatic expression that his earliest poetry embodied. To break the pentameter, that was the first heave, Pound wrote in The Pisan Cantos (Canto LXXXI), recalling his first encounter with late-nineteenth-century poetry but, more important, suggesting the aggressive and challenging approach he took to the task of poetic composition. Self-possessed and assured in his early work, he could fashion a narrative out of a shifting change,/A broken bundle of mirrors, as he writes in his remarkable reworking of Provenal traditions, Near Perigord, a poem that combines Dante, Provenal, and modernist form.

Pound contested traditional if not accepted conventions of poetic writing, replacing Swinburne with Arnaut Daniel, late Victorian elaboration with Imagism. The elegance and precision of the Chinese written character, where the ideogram replaced expansive metaphors, became his new focus. From 1908, when his first book, A Lume Spento, appeared, through 1923, when he was well under way with his lifetimes preoccupation, The Cantos (by 1923 there were 8; the final number, some only fragments, would be 117), Pound tested, revised, rejected, and recovered forms of poetic expression that became a new direction for poetry for a host of contemporaries, including H.D., T. S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, and Basil Bunting.

Pound began to remake his language on or about 1910: I was obfuscated by the Victorian language ... I hadnt in 1910 made a language ... to think in (LE, 19394). His poetic as well as cultural education had been alternately stultifying and liberating. It takes six or eight years to get educated in ones art, and another ten to get rid of that education, he declared (LE, 194). In criticizing his own Rossetti-influenced efforts to translate Guido Cavalcanti, for example, Pound explained that his mistake was in taking an English sonnet as the equivalent for a sonnet in Italian (LE, 194). They are not the same, and when he realized this it freed him to explore, expand, discover, and construct his version of these works.

The anti-Romantic essays of T. E. Hulme, the English philosopher, provided Pound with an early direction: beauty may be in small dry things ... the great aim is accurate, precise and definite description, wrote Hulme. By 1912, Pound would express similar ideas in a set of rules:

CLASSICS

CLASSICS