Richard Dawkins - An Appetite for Wonder: The Making of a Scientist

Here you can read online Richard Dawkins - An Appetite for Wonder: The Making of a Scientist full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Ecco, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:An Appetite for Wonder: The Making of a Scientist

- Author:

- Publisher:Ecco

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

An Appetite for Wonder: The Making of a Scientist: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "An Appetite for Wonder: The Making of a Scientist" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

With the 2006 publication of The God Delusion, the name Richard Dawkins became a byword for ruthless skepticism and brilliant, impassioned, articulate, impolite debate (San Francisco Chronicle). his first memoir offers a more personal view.

His first book, The Selfish Gene, caused a seismic shift in the study of biology by proffering the gene-centered view of evolution. It was also in this book that Dawkins coined the term meme, a unit of cultural evolution, which has itself become a mainstay in contemporary culture.

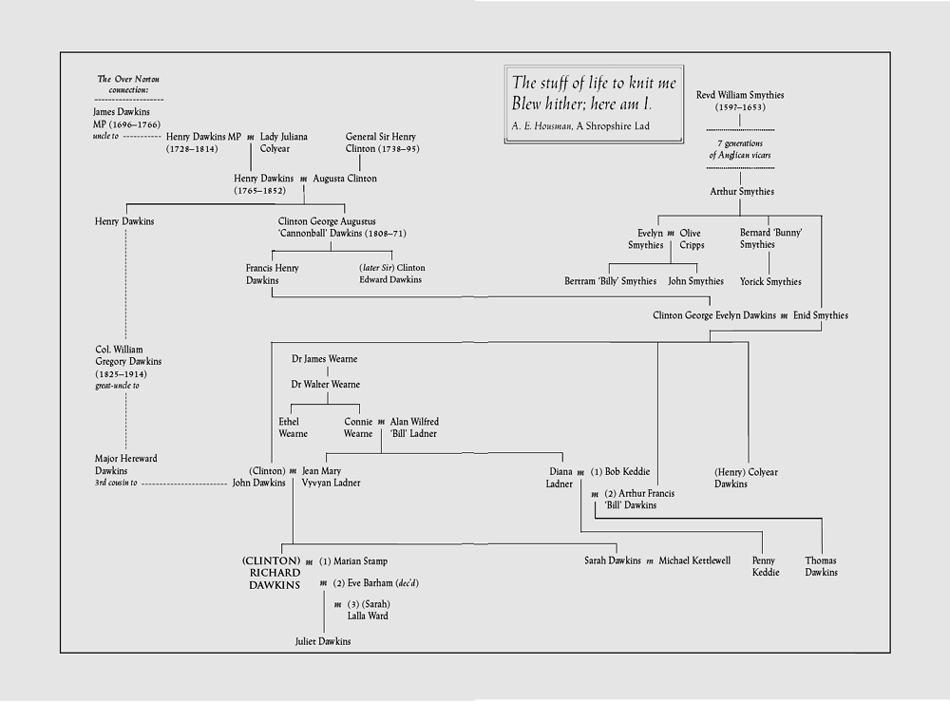

In An Appetite for Wonder, Richard Dawkins shares a rare view into his early life, his intellectual awakening at Oxford, and his path to writing The Selfish Gene. He paints a vivid picture of his idyllic childhood in colonial Africa, peppered with sketches of his colorful ancestors, charming parents, and the peculiarities of colonial life right after World War II. At boarding school, despite a near-religious encounter with an Elvis record, he began his career as a skeptic by refusing to kneel for prayer in chapel. Despite some inspired teaching throughout primary and secondary school, it was only when he got to Oxford that his intellectual curiosity took full flight.

Arriving at Oxford in 1959, when undergraduates left Elvis behind for Bach or the Modern Jazz Quartet, Dawkins began to study zoology and was introduced to some of the universitys legendary mentors as well as its tutorial system. Its to this unique educational system that Dawkins credits his awakening, as it invited young people to become scholars by encouraging them to pose rigorous questions and scour the library for the latest research rather than textbook teaching to any kind of test. His career as a fellow and lecturer at Oxford took an unexpected turn when, in 1973, a serious strike in Britain caused prolonged electricity cuts, and he was forced to pause his computer-based research. Provoked by the then widespread misunderstanding of natural selection known as group selection and inspired by the work of William Hamilton, Robert Trivers, and John Maynard Smith, he began to write a book he called, jokingly, my bestseller. It was, of course, The Selfish Gene.

Here, for the first time, is an intimate memoir of the childhood and intellectual development of the evolutionary biologist and world-famous atheist, and the story of how he came to write what is widely held to be one of the most important books of the twentieth century.

Richard Dawkins: author's other books

Who wrote An Appetite for Wonder: The Making of a Scientist? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.