Anthony Bourdain - Typhoid Mary

Here you can read online Anthony Bourdain - Typhoid Mary full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2005, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Typhoid Mary

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing PLC

- Genre:

- Year:2005

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Typhoid Mary: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Typhoid Mary" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Typhoid Mary — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Typhoid Mary" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Thanks to: Hope Killcoyne for her dogged and spectacular research on a difficult subject. Joel Rose, Gladys Bourdain (thanks, Mom), Michael Batterberry, the incredible Rose Marie Morse at Morse Partners. Brian Anderson. Assistant Comissioner of Geneology and Public Relations at the New York City Department of Records and Information Services, Ken Cobb, Bill Cobert of the Irish Historical Society, Dr. Kevin Cahill, Clem Berne, Melinda Gellman, Dimitri Kasterine. Maureen Hope. Peter Herb and Andrea Moss (legal documents). Jonothan Kuhn, Director of Arts and Antiquities for the New York City Parks Department, Ellen Morales at the Museum of the City of New York, Rebecca Tatem and Scott Norman at the BBC, Ed ODonnel, The New York Historical Society particularly Juliet Berman, Kathleen Hulser and the photo and library departments, the staff at the New York Public Library Reference and Microfilm departments. Lisa Westheimer. Paul Paradise of the Municipal Reference and Research Center, Bonnie Slotnick, Meryle Evans, Matt and Tracy at Kitchen Arts and Letters, my brother, Chris Bourdain, for getting me out to St. Raymonds Cemetary and helping all the way. Kim Witherspoon. Camelia Cassin. Philippe Lajaunie and Jose de Meireilles at Les Halles. Edilberto Perez, sous-chef extraordinaire, Pascal Graf, chef de cuisine (for covering my ass in the kitchen) and to all the chefs and line cooks Ive met in the last ridiculous and wonderful year. You know who you are.

Anthony Bourdain s books include the bestselling A Cooks Tour and Anthony Bourdains Les Halles Cookbook . His work has appeared in the New York Times and The New Yorker , and he is a contributing authority for Food Arts magazine. He is also the host of the Emmy Award-winning television show No Reservations . His latest book, Medium Raw , is a follow-up to Kitchen Confidential .

Sick

Historically, to be a cook, to prepare food for others, was always to identify oneself with the degraded and the debauched. As far back as ancient Rome, and as recently as pre-Civil War America, cooks were slaves. Untrustworthy, unpleasant, and more often than not, unhealthy, cooks in early twentieth-century Europe and America worked in hot, unventilated spaces for long hours. They were underpaid, underfed, and underappreciated their cruel masters despotic, megalomaniacal tyrants, parsimonious desk-jockeys, and brutish warders. Cooks tended as they still do to drink. And they died, usually at a young age, with their livers bloated by booze, their feet flattened, hands gnarled, faces ravaged, their lungs coated with the sediment of years of inhaling smoke, airborne grease, and bad air. Their brains were fried by the heat and the pressure and the difficulty of suppressing mammoth surges of rage and frustration, their nervous systems frazzled by mood swings which peaked and crashed with each incoming rush of business. They sweated and toiled in obscurity, cursed their customers, one another, their underlings, and their evil overlords. They cursed the world outside their kitchen doors for making them work like animals, for making them bend always to anothers will. For existing.

And yet they were almost always proud. Cooks knew then, as they know now, that the people out there, the ones who lived outside those swinging kitchen doors, the ones who owned homes, who went out to dinner or to the theater on weekend nights, the ones who had holidays off and who saw their loved ones for more than a few fleeting hours a week, were different. Civilians, as all cooks know, take their pleasures in different ways and, just as significantly, at different times. The rules they live by are different too. And just as cooks are not understood, they dont, cant, and never have understood them. The world of the nine-to-five worker, the property owner, the regular restaurant goer, the boss, is completely and maddeningly incomprehensible to those whove spent most of their lives bent over a hot range. As author Michael Ruhlman points out, cooks dont understand how others can live the way they live out there, in all that sloppy, unregimented luxury. Its messy. Its wasteful. Its scary and disorganized. Out there , things just dont seem to work the way they should.

For a cook, the well-ordered safety and certainty of the kitchen, however hot, cramped, and occasionally crazed, is a place of absolutes. The chef is the Absolute Leader. Food is always served on time. Cold food is served cold. Hot food is served hot. No one is late. No one calls in sick.

Let me repeat that: No one calls in sick.

The world outside the kitchen doors, to the mind of the cook, is imperfect a constant source of disappointment, a place of thousands of tiny betrayals which threatens at all times to intrude into their own territory. Cooks are territorial creatures. No Serbian militia or feral dog defends its terrain more fiercely, and seemingly unreasonably, than a cook protects his station. Mis-en-place , the general sense of things being the way they should be of being ready for anything extends only to the exit. Outside, its a strange and terrible place where things happen and dont happen in unpredictable and unforeseeable ways.

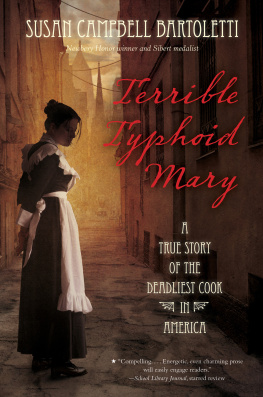

Mary Mallon, the woman who came (to her everlasting displeasure) to be known as Typhoid Mary, was a cook. Much has been written about Ms. Mallon over the years. There have been sensational newspaper accounts, plays, works of fiction, the predictable feminist reevaluations depicting her as the sad victim of an unfeeling, racist, sexist society bent on bringing a good woman down her persecution and incarceration the result of some gender-insensitive Neanderthals looking for a quick fix to an embarrassing public health problem. And there is an element of truth in almost all these characterizations. She was a woman. She was Irish. She was poor. None of these, listed on a resume in 1906, was going to put you on the fast track to the White House or a corporate boardroom or even a box seat at the opera.

Because, first and foremost, Mary Mallon was a cook. And her story, first and foremost, is the story of a cook. While that may not explain everything about some of the troubling aspects of her life, it explains a hell of a lot. Her tale has not yet, to my knowledge, been told from that point of view.

Little historical record of Marys life can be depended on and there are few recorded words or utterances from her own mouth. The accounts of the time, from others involved, directly or indirectly, with her case, are all too often self-serving, incomplete, sensationalistic, or plain wrong. Few, if any, take into account the worldview of the career cook.

There is one excellent, scrupulously researched, comprehensive and insightful telling of Marys story: Judith Walzer Leavitts Typhoid Mary: Captive to the Publics Health, an absolutely indispensable volume which should (and did, in my case) serve as a road map to anyone interested in her life and times. But Leavitts work focuses largely on the troubling public health and civil liberties issues raised by Marys incarceration by health authorities, drawing a meaningful comparison to todays AIDS crisis, and the moral quagmire officials encounter when confronted with otherwise blameless people who can, through casual contact with others, cause illness or death.

Thats not where Im going here. Im a chef, and what interests me is the story of a proud cook a reasonably capable one by all accounts who at the outset, at least, found herself utterly screwed by forces she neither understood nor had the ability to control. Im interested in a tormented loner, a woman in a male world, in hostile territory, frequently on the run. And Im interested in denial the ways that Mary, and many of us, find to avoid the obvious, the lies we tell ourselves to get through the day, the things we do and say so that we can go on, drag our aching carcasses out of bed each day, climb into our clothes and once again set out for work, often in kitchens where the smell, the surroundings, the ruling regime oppress us.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Typhoid Mary»

Look at similar books to Typhoid Mary. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Typhoid Mary and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.