Chapter One

Cold War Stand Off

N ow a decade old, Operation Enduring Freedom, designed to oust the Taliban from power, is an echo of a much bloodier war that was fought in Afghanistan over thirty years ago.Those who recall how grim Kabul was in the late 1970s will know that it became even grimmer after the arrival of Soviet tanks, jets and helicopters. Once more, geography, as in the earlier Korean and Vietnam wars, was to preclude the effective use of armour in Afghanistan. It was as if the Russians never bothered to heed any of the lessons of these previous conflicts and proceeded to learn the hard way from scratch.

The Soviet Union was at the height of its military power by the late 1970s. It was a vast monolith whose military resources were only rivalled by the worlds other Superpower the United States of America. Every year during Moscows Red Square military parades the Soviet armed forces put on displays of equipment bristling with firepower, designed to impress the population and cow its enemies. These parades also served to tip off Western intelligence of the existence of new equipment.The Soviets could not resist showing off.

For the previous two decades the Warsaw Pact and NATO had been at military loggerheads, facing off against each other in armed confrontation across central Europe in what was known as the Cold War. It was largely the threat of mutually assured destruction, should conflict break out and escalate to a nuclear war, that kept the two sides from coming to blows.

In fact the Cold War was anything but cold, with both the Soviet Union and US fighting a series of long and bloody proxy wars around the world. Ever since the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 they had been constantly testing each others resolve on foreign battlefields.The Soviet Union also had a track record of intervening with its neighbours it stamped out pro-democracy movements in Hungary and Czechoslovakia in 1956 and 1968 respectively, and on both occasions NATO had done nothing.

The Soviet intervention in Hungary was dubbed Operation Whirlwind. In response to calls for Soviet troops to leave the country, elements of two Soviet motor rifle divisions supported by tanks had rolled into Budapest and a further 75,000 troops streamed into the country. The Hungarian Army melted away and the revolutionaries were overwhelmed. In the fighting that followed, 3,000 Hungarians were killed. In total this invasion involved up to twelve divisions with 3,000 tanks.This was a conventional operation in which the Soviets employed the same tactics they had used during the Second World War.

In the case of Czechoslovakia, as part of Operation Danube, the 103rd Guards Air Assault Division (GAAD) arrived to seize Prague, followed by two motor rifle divisions. At the time the number of Warsaw Pact forces including Bulgarian, East German, Hungarian and Polish units committed to the invasion of Czechoslovakia was believed to be 250,000 troops and 2,000 tanks. This operation ran smoothly, mainly because of the minimal resistance offered by the surprised Czechs. The Soviets lost about 150 men, most as a result of accidents.

In the winter of 1979 Moscow was confident that a swift intervention in neighbouring Afghanistan to prop up the Marxist government would be a short-lived mission and probably go largely unnoticed. After all, Afghanistan was in the Soviets backyard and they were keen to aviod Islamic militancy spilling over into the neighbouring Soviet central Asian republics.

Despite Moscows vast and overwhelming array of military hardware, few of its troops had had any combat experience in recent years. While Soviet advisers had been posted to its client states, it was the Cuban Army that had often been called on to do Moscows dirty work in places such as Angola and Ethiopia. Nonetheless, Moscow had every reason to be confident that it could solve this problem on its doorstep and finally win the Great Game by securing dominant influence in Kabul. (All the time that India (and modern-day Pakistan) was part of the British Empire, the Great Game witnessed the British and Russians compete for control of Afghanistan as it formed a buffer between their respective empires.)

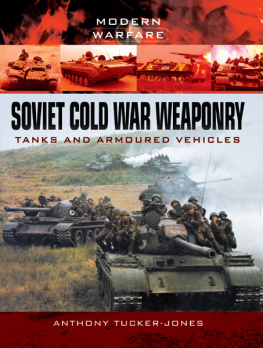

The Soviet Union certainly had the military muscle to pull off an invasion of Afghanistan. Although Moscow did not commit any armoured divisions to the invasion or subsequent occupation, the airborne and five motor rifle divisions involved were equipped with a wide variety of Soviet-designed armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs).

These formations deployed the T-54, T-55, T-62, T-72 and possibly a few of the newer T-80 main battle tanks (MBTs). Initially for the invasion the Soviets only used the older T-54/55 MBTs, but between 1981 and 1982 they were slowly replaced by the T-62, whilst some T-72s were possibly later used in the reconnaissance battalions of the motor rifle divisions. No confirmation exists of the T-80 MBT seeing combat, although it undoubtedly underwent trials in Afghanistan.

Tracked self-propelled artillery consisted of the 2S1 M-1974 (122mm), 2S3 M-1973, 2S5 M-1977 (both 152mm) and 2S9 (120mm mortar). Other tracked AFVs included the ASU-85 airborne assault gun, as well as the BMP-1/2 (Boevaya Mashina Pekhota infantry fighting vehicle) and BMD (Boevaya Mashina Desantnaya airborne combat vehicle). Wheeled AFVs were the BTR-60/70 armoured personnel carriers (APCs), BRMD-2 scout cars and 23mm gun trucks.

The BTR-60 was the standard Soviet amphibious eight-wheel APC of the day. The final model BTR-60PB was fully enclosed with a small turret armed with 14.5mm and 7.62mm machine guns. The BTR-60 and its successor, the BTR-70, were the standard APCs for three motor rifle regiments of a Soviet motor rifle division; the fourth was equipped with the tracked BMP-1 infantry combat vehicle. The newer BMP-2 infantry combat vehicle first saw service in Afghanistan in 1982 with the Soviet 70th Motor Rifle Brigade, which was later stationed in Kandahar.

The four-wheel BRDM-2 scout car had a similar turret to the BTR-60PB, carrying the same armament; minus the turret it was also used to carry Sagger and Spandrel anti-tank missiles and Gaskin surface-to-air missiles (although it is uncertain if the latter saw action in Afghanistan).

The airborne assault vehicles, the BMD and ASU-85, were only used by the airborne troops: principally the 105th Guards Air Assault Division followed by elements of the 103rd GAAD and the 38th Air Assault Brigade. Likewise the 2S9 airborne artillery assault vehicle entered service in 1981 and was deployed in Afghanistan with the Soviet airborne forces.

Two years later the Soviets began adding appliqu armour and smoke-grenade launchers to their tanks in an effort to combat the Mujahideens growing proficiency with anti-tank weapons. Some of the BMPs were also fitted with appliqu armour, while some BMPs and BTR-60/70s were up-gunned with a 30mm grenade launcher designed to provide suppressive fire.

The air-portable tracked SA-4 Ganef anti-aircraft missile carrier was deployed in Kabul, while the shorter-range wheeled rocket system, the FROG-7 (Free Rocket Over Ground), was first used operationally in Afghanistan in 1985 a case of using a sledgehammer to crack a nut!

Soviet AFVs were normally finished in dark olive-green and in some cases used a white invasion cross on their upper surfaces, a precaution usually employed when the Soviets expected to be engaging Soviet-designed armour. The cross was seen occasionally during 1979 80. In this case Moscow could not be certain that the Afghan Armys Soviet-supplied tanks would not resist the intervention. As it transpired, the Soviets were right to take these precautions. In May 1988, during the Soviet withdrawal, BTR APCs were photographed painted in the dark green but also with a very light brown camouflage, which was probably applied to other Soviet AFVs.