Penguin Monarchs

THE HOUSES OF WESSEX AND DENMARK

Aethelred the Unready

Richard Abels

Edward the Confessor

James Campbell

THE HOUSES OF NORMANDY, BLOIS AND ANJOU

William II

John Gillingham

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

Edward II

Christopher Given-Wilson

Edward III

Jonathan Sumption

THE HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK

Richard III

Rosemary Horrox

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

THE HOUSE OF STUART

[ Cromwell

David Horspool ]

William III & Mary II

Jonathan Keates

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

THE HOUSES OF SAXE-COBURG & GOTHA AND WINDSOR

Edward VII

Richard Davenport-Hines

Brunanburh

It

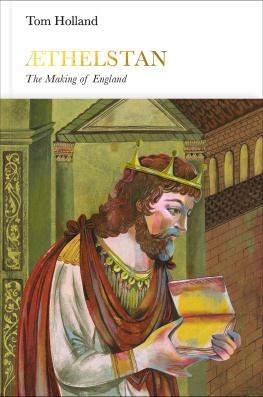

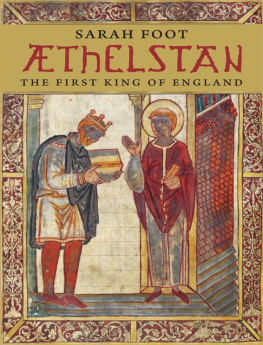

elstan cyning ldde fyrde to Brunanbyrig: Athelstan the king led the levy to Brunanburh. Then, in 927, Athelstan had ridden past the River Humber and entered York. Princes in the lands beyond the city, intimidated by the scope of his power, had scrabbled to acknowledge his authority. Never before had the grasp of a southern king reached so far. Wessex, Mercia and now Northumbria: all the peoples who spoke the conquerors own language, the whole way to the Firth of Forth, acknowledged Athelstan as their lord. In mark of this, he adopted a splendid and fateful new title, that of Rex Anglorum: King of the English. Athelstans horizons, though, were wider still. His ambitions were not content with the rule of the English alone. He aspired to be acknowledged as lord of the entire island: by the inhabitants of the various kingdoms of the Welsh, and by the Welsh-speaking Cumbrians of Strathclyde, whose kings held sway from the Clyde down to the Roman Wall, and by the Scots, who lived beyond the Forth in the highland realm of Alba. All had duly been obliged to bow their necks to him. In May 934, when Constantin, the King of the Scots, briefly attempted defiance, Athelstan led an army deep into Alba and put its heartlands to the torch. Constantin was quickly brought to heel. Humbly he acknowledged the invader as his overlord. When poets and chroniclers hailed Athelstan as rex totius Britanniae the king of the whole of Britain they were not indulging in idle flattery, but simply stating fact.

Britain, though, was not the world. The seas that washed the island were a menace as well as a moat. For a hundred years and more, they had borne on their tides war-fleets bristling with pirates from pagan lands. Scandinavia, a land so lost to cold and darkness that there was reportedly Its young men, hungry for land and contemptuous of the Christian faith, had found in the monasteries and kingdoms of Britain irresistibly rich pickings. Wicingas, their victims called them: robbers. Altars had been stripped bare of all their fittings, and kings bled of their treasure. Then, when there was nothing else left to take, the Wicingas the Vikings had moved in for the kill. In succession, the proud and venerable kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia had been hewn to pieces. Only the resolution of Athelstans grandfather, a shrewd and indomitable warrior-king named Alfred, had prevented Wessex from succumbing to an identical fate. Gradually, inexorably, bloodily, the fight had been taken to the Vikings. Strongholds lost decades previously to native rule had been won back. Athelstans conquest of York, as well as securing him the sway of Northumbria, had also terminated its rule by a lengthy sequence of Viking potentates. Britain seemed buttressed at last against the predations of the heathen.

But that was to reckon without the treachery of Constantin. In 927, he and rulers from across the island were obliged by Athelstan to swear publicly that they would never have dealings with idol worship: an oath calculated to remind them of their solemn duty as Christian kings. A decade on, though, collusion with the heathen proved a temptation impossible for Constantin to resist. Across the Irish Sea, in the Viking stronghold of Dublin, a warlord by the name of Olaf Guthfrithsson had long had his eyes fixed on York a city which, until its capture by Athelstan, had been held by his family. Just as Constantin yearned to cast off the yoke of his subordination, so Olaf dreamed of recovering his patrimony. It was a potent meeting of interests. By 937, the alliance was out in the open. That autumn, Constantin marched south. With him rode Owain, the King of Strathclyde. Meanwhile, at the head of an immense war-fleet, Olaf made the crossing from Ireland to join them. The combined armies of the three leaders, two of them the most powerful kings in Britain after Athelstan himself, and the third a notorious warlord, represented a potentially mortal threat to the nascent English realm. Abruptly, after a rise to greatness so dazzling as to have illumined the northern ocean with its brilliance, its future seemed menaced by shadow. Athelstan, brought the news, was numbed at first by the sheer scale of the calamity that threatened all his labours. Then, with a supreme effort of will, he geared himself for the great confrontation that he knew he could not duck. What option was there, in the final reckoning, save to ride and confront the invaders head on?

At stake, though, was not just the future of Athelstans kingdom. Beyond the world of men, in skies and lonely forests, the shudder of the looming battle was also being felt. As the King of the English rode northwards, the numbers in his train swelling with his advance, ravens as well as warriors began to follow in his wake. The birds were notorious creatures of ill omen: clamorous, untrustworthy, hungry for human flesh. Once, many generations previously, the English had believed that the raven was endowed so on battlefields were the birds known to serve their favourites as prophets of victory. This superstition, for all that the English had long since been redeemed from it, could not entirely be ignored. To march armed for battle and hear overhead the flocking of ravens was indeed to know that a time of slaughter was near. It was sufficient to perturb the warriors of even the most Christ-blessed king.