Codes, Secret Messages, and Cryptography

How do spies and the military send confidential information? With lemon juice, the Navajo language, and beer barrels, of course

TOM JAMIESON/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX

THIS FACSIMILE of the Enigma machine used by the Germans in World War II to encode communications is shown at the museum in Bletchley Park, the British code-breaking center credited with shortening the war by at least two years.

On September 18, 1698, a mysterious man, his head entirely enclosed in a metal mask, was escorted to Pariss Bastille prison, a fortress built to protect the city during the Hundred Years War. The inmate was supposed to be kept masked at all times, according to records kept by the prisons deputy governor. His name was never spoken aloud, and he was kept under strictest secrecy, fueling public fascination (who was that masked man?) not to mention speculation among philosophers, politicians, and writers. (Mystery! Mark Twain later wrote of the legend in The Innocents Abroad. That was the charm.)

Some claimed that the mans mask was hinged, allowing him to dine on delicate morsels from gold plates. Others said he was, in fact, a woman. The philosopher Voltaire created a sensation by claiming that the man was none other than King Louis XIVs older brother, who had been hidden to prevent a threat to the kings succession. But the chief architect of the mans enduring legend was novelist Alexandre Dumas, who made Voltaires theory part of his popular Three Musketeers novels, calling the prisoner the Man in the Iron Mask. He was, Dumas wrote, clothed in black and masked by a vizor of polished steel, soldered to a helmet of the same nature, which altogether enveloped the whole of his head.

The prisoners identity remained hidden for two centuriesthanks to the so-called Great Cipher designed by the father-and-son team of Antoine and Bonaventure Rossignol to encrypt monarchical messages. The code generated by the device was considered uncrackableuntil the late 1800s, when French military cryptanalyst tienne Bazeries discovered that it was based not on words but on syllables.

After unlocking the code, Bazeries used it to decipher the monarchs correspondenceincluding a letter about a cowardly general named Vivien de Bulonde, who had abandoned his troops during the French Piedmont campaign. Based on the contents of the letter, Bazeries determined that General de Bulonde was the Man in the Iron Mask and claimed to have solved the centuries-old mystery. To this day, however, the mans identity is subject to debate.

Keeping communications safe from adversaries has been an essential part of spy craft since at least the ancient Egyptians, who sent secret messages in hieroglyphics. The ancient Greeks wrote messages on mens shaved heads, then waited for the hair to grow back before dispatching their messengers. Ancient Chinese spies used a more alimentary approach: They wrote messages on silk, which they then covered with wax and swallowed.

In the 1st century, secret messages were written in the milk of the tithymalus plant, which vanishes when it dries and reappears when sprinkled with ashes. A 17th-century Italian scientist wrote on the shell of a hard-boiled egg with a mixture of alum and vinegar, which penetrated the shell to appear on the inside surface. Revealing the message was as simple as, well, breaking an egg.

Collectively known as steganography (hidden messages), these elementary methods were easily deciphered. The enemy could, after all, break an egg or shave a head. Clearly more sophisticated techniques were needed. Enter Julius Caesar, who in the 1st century B.C. developed one of the worlds first bona fide codes, known as a shift cipher. Heres a simple example: BRXUH ZHOFRPH . Now take every letter in that sentence and replace it with the letter that comes three positions before it in the alphabetan f becomes c and so on. (Youre welcome, by the way.)

Caesars cipher remained the spy worlds lingua franca until the 9th century, when a Muslim philosopher in Baghdad named Al-Kindi invented the science of cryptanalysis. Focusing not on developing codes but on cracking them, he essentially rendered the common cipher obsolete by developing a technique called frequency analysis. Though its now second nature to any crossword puzzle lover, Al-Kindi discovered that commonly repeated letters could reveal words and, subsequently, sentences. If your coded message has lots of x s in it, then x probably represents e , as e is the most common letter in written English, Simon Singh, author of The Code Book, tells LIFE. Al-Kindis breakthrough forced cryptographers to invent new, stronger, more fiendish ciphers.

During the Dark Ages, cryptography languished in Europeuntil 1467, when Italian Renaissance philosopher and architect Leon Battista Alberti revealed a major cryptological breakthrough: the cipher wheel. Composed of interlocking discs, it allowed spies to compose codes from mixed alphabets, thwarting frequency analysis. Albertis invention eventually led to ever more complicated encryption methodsincluding the supposedly unbreakable Vigenre cipher in the 1500s and the Rossignols Great Cipher.

Unfortunately, the development of these sophisticated codes escaped the attention of Mary Queen of Scotsa fact that ultimately led to her death.

The little Queen of Scots is the most perfect child I have ever seen, said the father-in-law of the young monarch, whose father, King James V, died a few days after she was born in 1542, making her queen of Scotland at less than one week old. The beautiful Catholic queen had an eventful life, marrying a French prince at 15, becoming a widow at 17, and enduring a bewildering series of entanglements and tragedies. (One of her three husbands became a drunk, and another was found strangled outside an exploded house!)

In 1567, Mary was defeated by rebellious Scottish nobles who stripped her of her crown and imprisoned her. Briefly freed, she sought the aid of her English cousin, Queen Elizabeth I, whofar from helpingconfined Mary in a series of castles for 18 years. Why? At the time, tensions between Protestants and Catholics were literally a matter of life and death. Many Catholics felt that Mary was the rightful queen of England as well as of Scotland, and that Elizabeth was illegitimate. So Elizabeth felt threatened by her cousinwith good reason: While imprisoned, Mary remained in touch with her Catholic allies through coded letters, until she tangled with Elizabeths wily spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham.

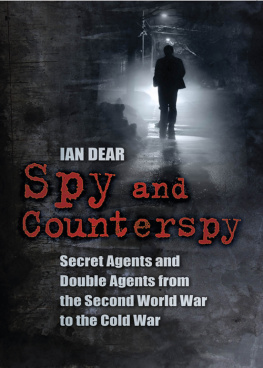

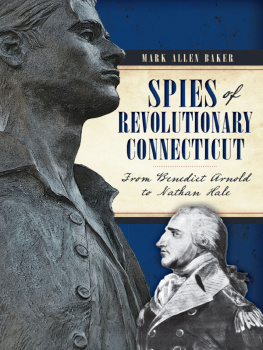

A rather fanatical Protestant, Walsingham created one of the worlds first intelligence networksa model for virtually every spy organization that followed. Known as the father of modern espionage, he employed techniques that endure today: the use of double agents, disinformation, bribes, threats, and psychological manipulation. He stationed secret agents everywhere from Scotland to North Africa and used cryptanalysts and experts in the art of opening and resealing wax-sealed letters without a trace.

In 1585, Mary was moved to Chartley Old Hall, a manor house in Staffordshire, England, where she spent her days knitting, reading... and once again passing coded letters to conspirators. But she was ultimately undone by the fact that she used a so-called nomenclator cipher that was scarcely more sophisticated than Caesars, replacing every letter of the alphabet with a fixed symbol.

Suspecting Marys schemes, Walsingham sent undercover hirelings to help convince her that her messages would be even more secure if she hid them inof all thingsbeer barrels equipped with hidden waterproof tubes. Mary enthusiastically embraced the idea, unaware that Walsingham was intercepting her letters and extracting and decoding the messages before sending them to their intended recipients.

On July 6, 1586, the monarchs fate was sealed when an idealistic 24-year-old Catholic named Anthony Babington wrote her a coded request to undertake the delivery of your royal person from the hands of your enemies and urging the despatch of the usurper. He wanted, in other words, to assassinate Elizabeth, but Walsinghams cryptanalyst easily cracked the code, revealing the so-called Babington Plot and leading to Marys beheading in 1587.

Next page