ZIGZAG

Reversal and Paradox in

Human Personality

Michael J. Apter

Copyright 2018 Michael J. Apter

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Author photo by Swadeep Patel

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: books@troubador.co.uk

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 978 1788038 867

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

To Mark Denneen

Without you, I might never have written this book, or any other book for that matter

When we dismiss as absurd that which does not seem to us to be logical, we merely prove that we know nothing about nature.

Marc Chagall.

(Cited in Chagall by Jacques Damase,

New York: Barnes and Noble, 1963.)

A zigzag can be the shortest distance between two points.

Anon.

Contents

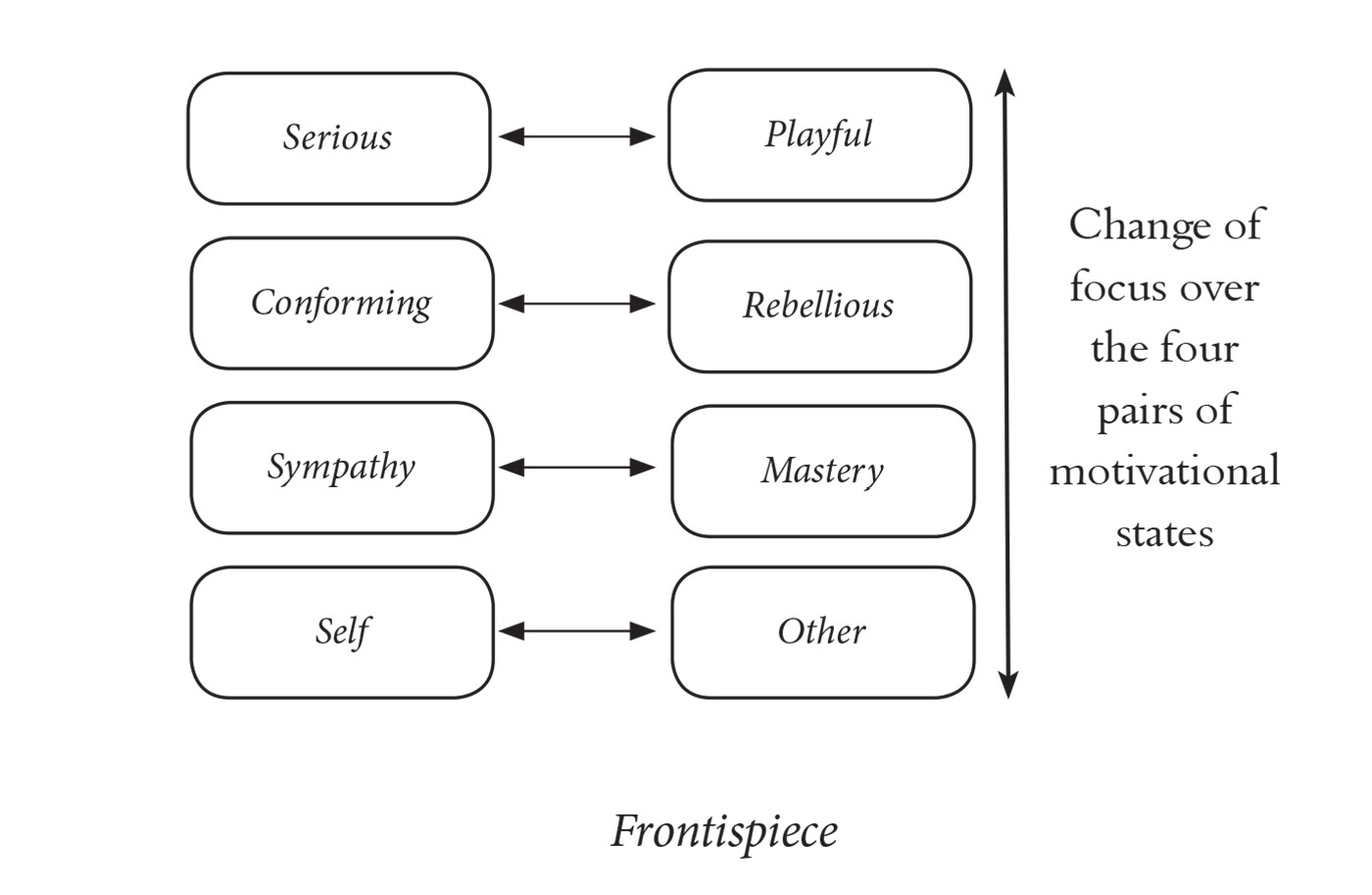

Four self-contradictory people, illustrating the four basic pairs of contradictory motivational states that underlie personality.

How reversals occur between opposite motivational states, with examples from everyday life. All about you.

The need to go beyond both trait and situational theories of personality: understanding people in their full complexity.

Play, risk and arousal. Functional frames and frames that are problematic.

The enjoyment of bad feelings: Movies, sex, art, humor, and others.

External reward and the redefinition of situations as serious. Behaviorism.

Hedonic, Franklin, Abilene, and other paradoxes arising from identification with others.

Obedience, disobedience and other forms of opposition. How destruction can be creative.

The limits of persuasion by force. Interrogation. How to handle a murderer on the run.

Strange compliance: The Stockholm syndrome, concentration camps, show trials, domestic violence.

Explanation of apparently irrational effects studied by behavioural economists.

Why happiness is so ephemeral. Peak experiences. The need for a Realistic psychology.

The different types of paradox make up a five-level hierarchy.

Advantages of reversals in problem-solving, self-control and motivational intelligence. Exploration. Terrorism.

Contradiction and reversal are widespread in biology. Zigzag. Para-evolution.

Reversals between Opposite Motivational States

Acknowledgements

No man is an island, and this is particularly true of an author, who must remain open to every possible source of information and inspiration during the writing of his or her book. There are more people, therefore, than I can possibly acknowledge here for their help. But I would at least like to place on record my gratitude to Robert Blackstock, Thea Edwards and Mary Margaret Livingston, all of Louisiana Tech University, for their expert advice. I am also most appreciative of feedback from Gareth Lewis, Jennifer Tucker, Jay Lee, Jolena Juers, Brandon Moore, Brian Hindman, James Tornabene, Ann-Marie Rabalais, Christophe Lunacek, Eugnie Rambaud. I would also like to thank Jean Rambaud who, in the course of translating this book into French for publication in France by Dunod InterEditions, made many useful suggestions. I also profited from the creative collaboration on the concept of Motivational Intelligence with Tim Routledge, Danielle Swain, and their colleagues at Experience Insight Ltd, and with James Parker of Trent University, Canada.

My thanks are due to the South Carolina Department of Public Safety, Office of Highway Safety, for allowing me to cite some of the Apter International findings on seat belt usage and driving under the influence of alcohol, and for sponsoring this research.

My special thanks are with Joe Shillito, Hannah Dakin and their colleagues at Troubador Publishing.

It goes without saying, but I am pleased to say it anyway, that my major indebtedness, both personal and professional, is to my wife Mitzi Desselles.

Preface

If you are like me, you rarely open a nonfiction book and start reading at chapter one. Personally, I try to get an impression of what a book is about by flicking through the pages and seeing what catches my eye. I also turn to the end to see what final conclusions are provided. If all this looks interesting, then I turn to the first chapter (and perhaps buy the book). I do essentially the same with an electronic book.

In case you have started here rather than at the end, I can tell you that this book is centred on the idea that human personality is essentially dynamic and changing, and that the trait concept, which is at the basis of nearly all personality research, tends to be simplistic and limiting. After all, if you tell someone This is how you are, you restrict, at the outset, their possibilities for change. You also in some sense restrict them to less than they could be.

Looking at human personality in this more dynamic way can open up new vistas for research and be liberating to patients and clients. It can also explain various paradoxes that arise in everyday behavior. This is not to deny that there are some kinds of consistency, but these consistencies tell only part of the story, and, I believe, in many ways, the less interesting part. We change from day to day, hour to hour, even minute to minute. The engine for this change is motivation: Now you want this, now you want that. As our motives change, so we see the world from different perspectives and become different kinds of people. Indeed, we can even, in short order, contradict ourselves. Well-being involves, among other things, our ability to navigate through such innate contradictions and turn them to our advantage.

The theme of the book is not just the limitation of trait theory. More positively, it provides an alternative way of looking at things by arguing that there is a structure underlying everyday behavior. There may be inconsistency but there is also pattern underlying this inconsistency. Specifically, I suggest that there are four pairs of contradictory motivations. This structure will inform the organisation of the book. We shall look at these contradictions and see how they play out in peoples lives, sometimes helpfully and sometimes harmfully, often producing paradoxes and anomalies. In doing this I shall draw particular attention to these paradoxes, since they are overlooked or downplayed in modern personality research. In this way I hope to provide a more realistic account of what it means to be human not to say a more colourful and surprising one.

The book is organised in three sections. In the first, I introduce the basic ideas, all of which derive from Reversal Theory. These include such ideas as reversal and motivational state. In the second part I take each of the four pairs of motivational states separately and show examples of the paradoxes that they generate. In the third section I apply the ideas generated in the first two sections to our understanding of economic behaviour, and to the nature of happiness. Finally, I relate all this to some fundamental biological processes. There are also some Appendices which provide background information.(1)