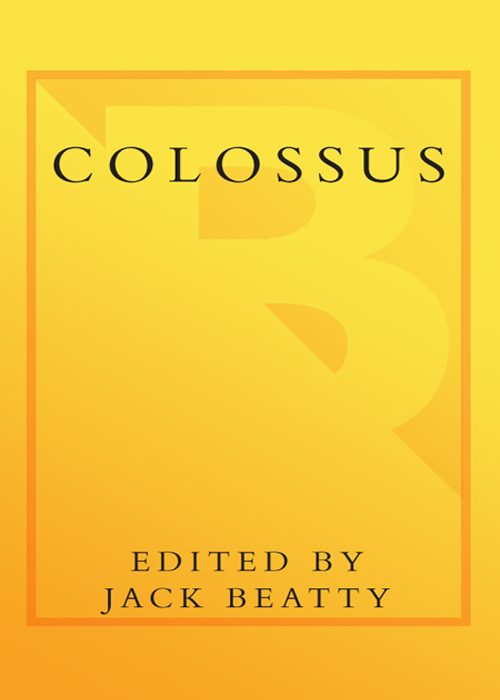

H OW THE C ORPORATION C HANGED A MERICA

JACK BEATTY

BROADWAY BOOKS / NEW YORK

CONTENTS

For example, consider how ABC News has handled some recent stories to which its parent company, Disney, was sensitive. According to a report by Jane Mayer in The New Yorker, ABC news executives killed a story alleging that lax hiring practices at a Disney theme park had allowed pedophiles to get jobs; killed another about high executive pay because, sources told Mayer, no one wanted to call attention to the extraordinarily rich pay package of Disneys chairman, Michael Eisner; and killed stories on a cruise ship and on the movie Chicken Run, in the former case partly because Disney owns a rival cruise line, in the latter because they thought it would give free publicity to Disneys corporate rival, Dream Works. See Jane Mayer, Bad News, The New Yorker, August 11, 2000, pp. 3233.

Tired of what the chairman of Deloitte & Touche calls a shakedown by politicians, a number of giant corporations, including Xerox, GM, Sara Lee, and Merck, have joined with Ralph Nader, the Sierra Club, and the League of Women Voters, to issue a report endorsing campaign finance reform. See Molly Ivins, $9 million to nail Cisneros for a misdemeanor, in the Boston Globe, September 11, 1999, op. ed. page.

So-called socially responsible investing, which reflects the rising awareness of the conflict between market decisions and moral values, now accounts for $2 trillion, or 13 percent, of all money managed professionally, up 82 percent just since 1997, since which time the number of socially responsible mutual funds has increased from 55 to 175. See John Hechinger and Joseph Pereira, Sympathizers Scramble to Rid Ben & Jerrys of Two Unwanted Suitors, in Wall Street Journal, February 4, 2000, p. 1.

The late Michael Harrington, the author of The Other America (1962), which documented the depth of poverty amid American affluence and seeded the climate for Lyndon Johnsons War on Poverty, was insightful about the nature of this emerging socialization. He remained a Marxist to the end, Maurice Isserman writes in his biography of Harrington, regarding capitalism as a self-contradictory system that drew people together in productive enterprise and yet drove them apart through the unequal distribution of resources. He called this an unsocial socialization. From Maurice Isserman, The Other American: The Life of Michael Harrington (New York: Public Affairs, 2000), p. 361.

This list is adapted from Richard Hofstadter in Social Darwinism in American Thought (Boston: Beacon, 1983), p. 46.

The federal government mapped the conquest of space. Between 1824 and 1828, the Army Corps of Engineers worked on ninety-six transportation projects, most of which were either state or privately owned roads and canals. By the time the Corps of Engineers wrapped up its work under the General Survey Act around 1840, nearly fifty new railroads had been surveyed. All told, more than one hundred and twenty West Point graduates worked on American railroads prior to the Civil War, all in supervisory capacities. One writer declares that up to 1855 there was scarcely a railroad in the country that had not been projected, built, and in most cases, managed by the Corps. From an anonymous expert reader for the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

The economist Robert Heilbroner distinguishes five waves of invention that have imparted developmental thrust to capitalism. The first of these waves was the Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries that brought the cotton mill and the steam engine, along with the mill town and mass child labor; a second revolution gave us the railroad, the steamship, and the mass production of steel, and along with them new forms of economic instabilitybusiness cycles; a third revolution introduced the electrification of life and the beginnings of a society of mass semi-luxury consumption; a fourth rode in on the automobile that changed everything from sex habits to the locations of population; a fifth electronified life in our own time. From Robert L. Heilbroner, 21st Century Capitalism (New York: Norton, 1993), pp. 3536.

Railroading could be grisly work: 72,000 employees were killed on the tracks between 1890 and 1917; and close to 2 million injured; another 158,000 killed in repair shops and roundhouses. From Alan Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982), p. 91.

Capitalism, the political scientist John Mueller writes in Capitalism, Democracy & Ralphs Pretty Good Grocery (1999), encourages people in business to be honest, fair, civil, compassionate... not because those qualities are valued for themselves, but because of acquisitiveness and greed. If you want repeat customers, virtuous conduct pays.

On the other hand, [B]ecause the developing world is still so poor, the economist Paul Krugman cautions, what looks to careless observers like exploitation is often far better than the alternative. See Paul Krugman, An American Pie, New York Times, Feb. 16, 2000, p. A29.

The March 1881 issue... sold out seven editions and brewed a great controversy about corporate abuse and government regulation that foreshadowed the great debates of the following decades. From Ellery Sedgwick, A History of the Atlantic Monthly, 18571909 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994), p. 157.

John D. Rockefeller and his brother, William.

One historian calls the following letter by Williams father, Commodore Vanderbilt, legendary in the annals of American business. Vanderbilt is writing to former associates trying to swindle him:

Gentlemen:

You have undertaken to cheat me. I wont sue you, for the law is too slow. Ill ruin you.

Yours truly,

Cornelius Vanderbilt

H. W. Brands, Masters of Enterprise (New York: The Free Press, 1999), p. 20.

In The Curse of Bigness Louis D. Brandeis listed the Newspaper Trust, the Writing Paper Trust, the Upper Leather Trust, the Sole Leather Trust, the Woolen Trust, the Paper Bag Trust, the International Merchant Marine, the Cordage Trust, the Mucilage Trust, the Flour Trust, the Standard Oil Trust, the Steel Trust, the Tobacco Trust, the Shoe Machinery Trust, the Sugar Trust, and the Rubber Trust. The Curse of Bigness: Miscellaneous Papers of Louis D. Brandeis (New York: Viking, 1935), p. 117. For a comprehensive discussion of the trust question see Antitrust: Perceptions and Reality in Coping with Big Business, Case 23 in Management: Past and Present by Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., Thomas K. McCraw, and Richard S. Tedlow (Cincinnati: International Thomson Publishing, 1996). McCraw describes the trust movement as driven by the powerful tendency of business executives to cooperate with competitors in associations or mergers. The overcapacitythe glut of goodscreated by machine-driven increases in productivity led corporations to combine with each other to limit the total output of their plants, maintain the price levels of their goods, and discourage the entry of new firms into their lines of business (Module 55).

In his man-and-his-times biography of Taylor, The One Best Way, a volume in the Sloan Technology Series, Robert Kanigel writes: In 1913, Life carried a cartoon showing a man and woman in an office, their workplace embrace broken up by the Efficiency Crank: Young man, are you aware that you employed fifteen unnecessary motions in delivering that kiss?

Henry Ford II, when asked what it was like competing against General Motors

Next page