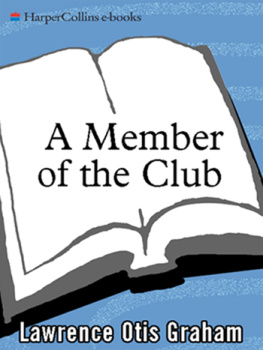

To my brilliant wife, Pamela Thomas-Graham.

Thank you for making my dreams come true.

A lthough I spent six years researching Our Kind of People , I could never have been prepared for the controversy that it elicited from various groups upon its initial publication. Although there is a constant cry for diversity in our media, our literature, our history books, and in our communities, it became obvious to me that there are certain narrow stereotypeseven within an integrated societythat people are simply unwilling to relinquish. The stereotype of the working-class black or impoverished black is one that whites, as well as blacks, have come to embrace and accept as an accurate and complete account of the black American experience. Our Kind of People upset that stereotype. And it upset many peopleparticularly blackswho have been taught never to challenge a stereotype that we had been saddled with since slavery.

For many people, this book is a political or social hot potato in the sense that even though most blacks talk about the issues of elitism, racial passing, class structure, and skin color within the black community, they dont want to see it broadcast in a book. For a few black members of the media, the topic struck too close to their own past experiences of being excluded by snobbish members of the black elite. Some of them quietly told me that they were glad that I wrote the book because it was disproving the stereotypes, but that they could not publicly support the book because their white audiences would find the concept of rich, educated blacks too threatening and because their black audiences would find the subject too painful.

An extensive national tour uncovered many surprises during media interviews, personal appearances, and Internet dialogues, as well as at high-end cocktail parities.

A short time after Our Kind of People was first published, there was a series of discussion panels set up in different cities so that members of the black elite could come together and share their views on the book and address the controversy that had arisen around the issue of class within the black community. Each of these panel discussions was preceded by a somewhat formal cocktail party, where guestsmany of them members of old-guard social clubs or prominent familieshad the opportunity to mingle with old friends as well as representatives from the media. Although the largest event took place at the Harvard Club in New York City, the most memorable one occurred on a hot spring evening in Los Angeles.

Youd better not show your face in Marthas Vineyard this summer, snapped an attractive Yale graduate as she remarked how she and some of her other black friends were responding to the controversy around Our Kind of People . Shed evidently seen me in Oak Bluffs in prior years and had heard that many people were disturbed either because their names hadnt appeared in the book or because they believed that wealthy blacks shouldnt be talking about their accomplishments.

I felt both groups were being unreasonable and I told the woman so. Some black folks may be uncomfortable to learn that there are several generations of elite blacks who live in a separate world, but like white people, blacks also have to learn to accept the facts in our history, I remarked. I dont think the black upper-class crowd should be ashamed of its success any more than the WASP elite, Italian elite, or Jewish elite.

You opened a real can of worms, another woman remarked as she stood by listening. Folks dont want to hear about rich blacks unless were playing basketball, singing rap music, or doing comedy on TV.

As casual as that remark was, it was actually an accurate assessment of many black peoples response to a book that I had spent six years researching. While a few whites expressed amazement that there had been black millionaires and black members of Congress as far back as the late 1800s (one white TV anchor told me on live television that if I had not displayed photos of the well-known entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker and her familys 20,000-square-foot 1902 mansion in New York, he would never have believed that a black millionaire existed at the turn of the century), most were fascinated by how closely class structure and elitism among blacks mirrored that found in other racial and ethnic groups.

A large number of blacks, however, were not so comfortable with the 120-year history of the black upper class in America. Many with ties to these families, organizations, schools, fraternities, or summer resorts accepted this history with prideso long as they did not have to admit their status in the company of non-elite blacks.

I dont want the other black folks in Atlanta to think Im looking down on them, explained a millionaire surgeon who attempted to avoid association with the old-guard clubs, schools, and institutions whenever they were mentioned in mixed company.

And this is why I have concluded that although every racial, ethnic, and religious group in the United States claims to want a piece of the American dream, there is no group that apologizes more for its success than black people. The cultural identity or integrity of a black millionaire rap star, basketball player, or TV performer will never be questioned. But an equally wealthy black professional with an upper-class background and a good education will earn the label of a sellout or a Negro trying to be white.

The black Yale grad with the long mane of hair in Los Angeles was aware of that fact when she warned me about showing up on the beaches of Marthas Vineyard. In the cities that had preceded L.A., the people attending these gatherings had represented a rather insular circle. They were members of old-guard families and social clubs like the Links or Boul; individuals who had attended the schools, camps, and cotillions that had been written about; and wealthy physicians or businesspeople who understood and embraced the world captured in the book.

But something about this gathering in L.A. seemed differentand intriguing. For the first time, there seemed to be people present who did not come from the world of the black elite. Yes, they were black, but they were not uniformly wealthy or old-guard. Since the book was gaining attention through its selection by the Book-of-the-Month Club, its appearance on various bestseller lists, numerous magazine excerpts, and many positive reviews and features in the New York Times and the Washington Post , it was attracting an audience beyond the initial wealthy black and wealthy white readers. It was hitting the mainstream.

Lawrence, I dont think these are our kind of people in this room, remarked a Los Angeles doctor friend of mine who had grown up with me in Jack and Jill and had summered in Marthas Vineyard.

Im hearing some pretty nasty stuff from these folks, remarked a friend of my mothers, who had brought some of her friends from the Links. She moved closer to me. Some of us are leaving, so I dont know if you really want to be here.

That very week, the Los Angeles Times had run a front page feature story about the book and about the wealthy black people and organizations that had been profiled in it. Although it spoke glowingly about high-powered black Angelenos, the article and surrounding discussion clearly did not sit well with certain wealthy blacks who had not been included. And the middle-class blacks were enraged to discover that there was a circle of elite black people, institutions, and activities that excluded them. If talk about the right debutante cotillions and best black schools and summer camps hadnt already offended them, the accompanying photo of me standing on Beverly Hills Wilshire Boulevard convinced them that the black elite was existing completely outside the mainstream black world. Of course this was not entirely true.